Blog Post

George Earle: The diplomat who couldn’t stop brawling with Nazis

By Jonathon Van Maren

Every so often, I read a biography and wonder: How have I never heard of this person before? Exiled Emissary: George H. Earle III, Soldier, Sailor, Diplomat, Governor, Spy by Christopher J. Farrell is one of those. George Earle III (1890-1974) was a patrician, a politician, a diplomat, and one of only two Democrats to serve as governor of Pennsylvania between the American Civil War and the Second World War. During that period, he managed to involve himself in nearly every major historical event, and his front-row seat to the unfolding conflicts of the 20th century transformed him from FDR’s man abroad to an avowed anti-Communist who maybe—just maybe—could have played a role in changing the course of history.

After serving in the First World War, Earle became one of the Democratic Party’s rising stars. In 1933, Franklin Delano Roosevelt appointed him minister to Austria, and he promptly developed a close relationship with Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss, the man who suppressed both the socialists and the Austrian Nazi Party in an attempt to stabilize his country. From Austria, Earle sent regular, detailed reports to FDR on the brawls between the Nazis and other political factions. Earle saw the Nazi threat early and gained a reputation for being on the front lines of battle while gun smoke was still hanging in the air, insisting on seeing the conflicts for himself in order to report on events firsthand. Dolfuss was assassinated shortly after Earle left in 1934.

Earle ran for governor of Pennsylvania that year, where he distinguished himself as a broker of bipartisan deals and signed an equal rights bill that “enable[d] any Negro in Pennsylvania to bring suit for damages if he is discriminated against by a hotel, restaurant, shop, or theatre” well before the civil rights movement broke through American consciousness. Farrell’s biography describes an extinct species—a muscular liberal and hardcore anti-Communist who was keenly aware of the dangers of the Left. It is interesting to read about a man like Earle in an era where, according to modern progressives, there are mere inches between calling for tax cuts and becoming Hitler.

In 1940, Earle was appointed FDR’s minister to Bulgaria. His personal charisma and genius for friendship landed him relationships with King Boris and Foreign Minister Haralan Popoff, sending detailed notes on their conversations with Hitler, Ribbentrop, and the Nazi inner circle back to FDR (the Germans badly wanted the Balkan oil fields). Farrell relates one interesting tidbit in which Earle had a personal confrontation with Hitler—at least as reported by the Historical Society of Pennsylvania:

A year into his assignment the former Pennsylvania governor made headlines when he purportedly told Adolf Hitler during a private meeting that “I have nothing against the Germans, I just don’t like you.”

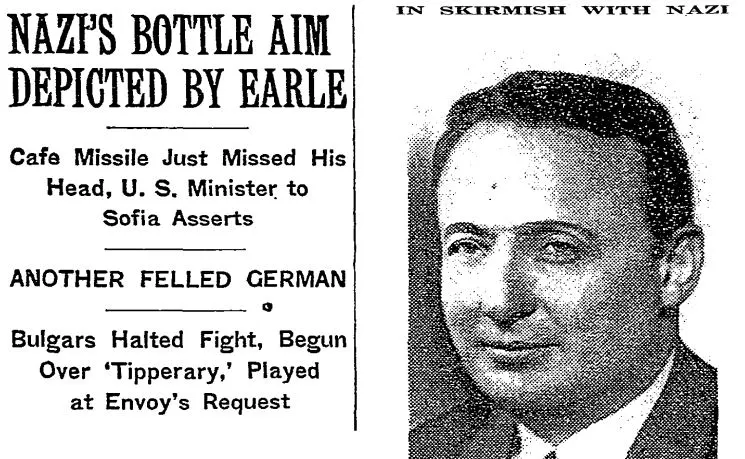

Regardless of whether that incident actually took place, Earle’s other confrontations with Nazis make it at least believable, as his diplomacy was frequently physical. In February 1941, for example, Earle took part in what one reporter called “The Battle of the Bottles in the Balkans.” Both the Allies and the Nazis had personnel stationed in the Bulgarian capital of Sofia, and the spies and diplomats of both sides frequented the same establishments. One night, Earle asked the band at the bar to play “Tipperary.” This greatly offended the Nazis, which greatly gratified him. According to Earle’s account, a Nazi tried to wallop him with a wine bottle while he made his way to the loo, and this “unprovoked attack irritated me considerably,” so “I smashed him in the face, knocking him down and causing his face to bleed.”

An immediate brawl erupted in which the Bulgarians rallied to Earle and the Germans joined their wounded compatriot, with Earle eventually getting hustled out of the bar. This caused a press sensation on both sides of the Atlantic; the Los Angeles Times ran an article under the headline: “Nazi Beaten by Earle, Envoy, Reported Dying,” which alleged that Earle had fractured the Nazi’s skull. The severity of Earle’s beating was unconfirmed, but he likely put the man in the hospital. The Nazi press branded him a criminal and an enemy, a designation exacerbated by another scuffle in Sofia which resulted in a German soldier trying to pull him out of his car by his leg. Earle kicked the man, gave his companion a “straight left to the jaw,” and then turned his car around and tried to run them down. “I chased them up on the sidewalk with my small car,” the diplomat related. “They got in a doorway and I couldn’t get at them, so I drove home.”

READ THE REST OF THIS COLUMN AT THE EUROPEAN CONSERVATIVE