Blog Post

Walker Percy: If Roe v. Wade could fall, what else might be possible?

By Jonathon Van Maren

FIRST PUBLISHED AT FIRST THINGS

Roe v. Wade was overturned on June 24, 2022. The pro-life movement had worked toward this goal for nearly half a century; at several points, it had seemed impossible. I was in Washington, D.C., that weekend and walked to the Supreme Court to see the crowds of angry protestors roiling in front of the steel fences. The opening lines of Walker Percy’s dystopian novel Love in the Ruins came to mind: “Now in these dread latter days of the old violent beloved U.S.A. and of the Christ-forgetting Christ-haunted death-dealing Western world I came to myself . . . and the question came to me: has it happened at last?”

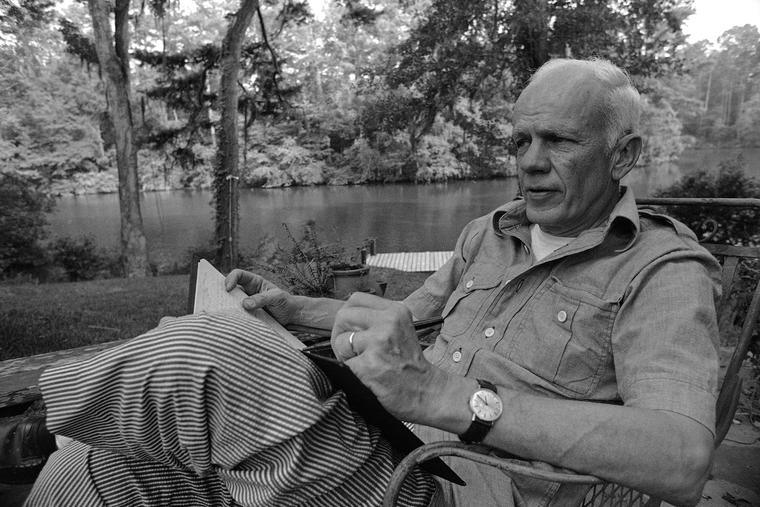

It had indeed, and I thought that weekend of the thousands upon thousands of pro-life Americans who never lived to see it. One of them was Walker Percy, the Louisiana novelist and Catholic philosopher who died in 1990 and wrote much about abortion. As a writer, Percy was offended by the way words had been twisted to hide the reality of abortion. In 1981, Percy noted in the New York Times that novelists who discuss abortion are “perhaps more sensitive to the atrocities of the age than most. People get desensitized . . . a 20th century novelist should be a nag, an advertiser, a collector, a proclaimer of banal atrocities.”

Percy was both prescient and correct. The post-Roe media coverage of the American abortion wars almost entirely ignores the main character in this bloody drama: the pre-born child. We hear about “abortion providers” and “healthcare” and “products of conception” and “reproductive rights.” What we do not hear about, in Percy’s words, are “fetuses flushed down the Disposall.” We glimpse them every now and again when corpses are pushed into public consciousness by pro-life activists, but rarely do we discuss the fact that abortion is not about a what, but a who.

Percy observed this rhetorical sleight of hand with contempt. Abortion supporters, he noted, were engaging in a “particularly egregious example of doublespeak” and “as a novelist I can recognize meretricious use of language, disingenuousness, and a con job when I hear it.” For example, the idea that we do not know when life begins is nonsense—that fact is, Percy wrote, “known to every high school student and no doubt to you the reader as well, that the life of every individual organism, human or not, begins when the chromosomes of the sperm fuse with the chromosomes of the ovum to form a new DNA complex that thenceforth directs the ontogenesis of the organism.”

In fact, Percy wrote, the “wonderful irony” is that it is science, not the dogmas of the church, that have revealed so much about when life begins and the “secular juridicial-journalistic establishment” that denies it. Pro-life laws are a result of expanding scientific knowledge—indeed, that is the argument pro-life doctors made in advocating for these laws in the nineteenth century. Percy writes:

Please indulge the novelist if he thinks in novelistic terms. Picture the scene. A Galileo trial in reverse. The Supreme Court is cross-examining a high school biology teacher and admonishing him that of course it is only his personal opinion that the fertilized human ovum is an individual human life. He is enjoined not to teach his private beliefs at a public school. Like Galileo he caves in, submits, but in turning away is heard to murmur, “But it’s still alive!”

Indeed, these youngest members of the human family are alive, which is why so many abortionists openly admit that the “healthcare” they provide involves killing them. “If I had anything to say to the liberals,” Percy told one interviewer,

it is that I agree with them on almost everything: their political and social causes, and the ACLU, God knows, the right to freedom of speech, to help the homeless, the poor, the minorities, God knows the blacks, the third world—their hearts are in the right place. It’s actually a mystery, a bafflement to me, how they cannot see the paradox of being in favor of these good things and yet not batting an eyelash when it comes to destroying unborn life.

In Percy’s last novel, The Thanatos Syndrome, a priest excoriates the medical field, telling the main character, Tom More: “You are a member of the first generation of doctors in the history of medicine to turn their backs on the oath of Hippocrates and kill millions of useless old people, unborn children, born malformed children, for the good of mankind—and to do so without a single murmur from one of you.”

Fortunately, Percy was not quite right. There have been many murmurs from many doctors; the fall of Roe v. Wade was brought about by the collective chorus of untold thousands of Americans who refused to accept that their nation endorsed the killing of children in the womb. “Americans are the nicest, most generous, and sentimental people on earth,” Percy once observed. “Yet Americans have killed more unborn children than any nation in history.” But another fact is also true. America declared that abortion is a constitutional right—and then declared, after a half-century of slaughter, that it is not. In the wake of Dobbs, stunned journalists asked: If Roe can fall, what else might be possible?

It is an encouraging question to consider. As Percy wrote in Love in the Ruins:

Is it that God has at last removed his blessing from the U.S.A. and what we feel now is just the clank of the old historical machinery, the sudden jerking ahead of the roller-coaster cars as the chain catches hold and carries us back into history with its ordinary catastrophes, carries us out and up toward the brink from that felicitous and privileged siding where even unbelievers admitted that if it was not God who blessed the U.S.A., then at least some great good luck had befallen us, and that now the blessing or the luck is over, the machinery clanks, the chain catches hold, and the cars jerk forward?

Maybe. Or maybe the death of Roe can lead us to ask the question: If God in his providence has allowed Roe v. Wade to fall, what else might be possible?