Literature, Reviews

Cormac McCarthy gave us the best portrayal of fatherhood in American literature

By Jonathon Van Maren

Cormac McCarthy, a titan of American literature, died this week at the age of 89 at his home in Santa Fe, New Mexico. The author of twelve novels, he was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 2006 for The Road, the viscerally powerful story of a father and son traveling across a post-apocalyptic America that was packed with sentences like this one: “The soft black talc blew through the streets like squid ink uncoiling along a sea floor and the cold crept down and the dark came early and the scavengers passing down the steep canyons with their torches trod silky holes in the drifted ash that closed behind them as silently as eyes.”

Like Faulkner, McCarthy wrote by his own rules—but he was better than Faulkner, and his impact on American literary culture was profound.

McCarthy was born to an Irish Catholic family on July 20, 1933, in Providence, Rhode Island. He grew up comfortably middle class in Tennessee, served in the Air Force in the 1950s, and was on his second marriage—to English singer Anne DeLisle—by the time the 1960s were out (they separated in 1976). His first marriage, to college sweetheart Lee Holleman, produced a son. McCarthy wandered; he lived in Europe for awhile, headed back to Tennessee, and later moved to El Paso, Texas before settling in Santa Fe. He divorced his third wife, Jennifer Winkley, in 2006. He leaves behind two sons, Cullen and John. The Road is dedicated to John.

Faulkner’s last editor worked on his first book, The Orchard Keeper, which was published in 1965 but failed to land with the public. McCarthy kept at his craft with the assistance of writer’s grants. His 1985 Western novel Blood Meridian, the bleakly violent story of scalp hunters in the mid-1800s, gained little attention at the time but is now considered one of his best. All the Pretty Horses, the first in his Border Trilogy, was his first commercial success—until then, he had sold fewer than 5,000 copies of the hardcover editions of any his books. He reacted to literary fame by refusing most interviews, eschewing book signings, and avoiding the public so assiduously that he earned comparisons to J.D. Salinger.

McCarthy’s reputation for dark, brutal writing is well-earned, although it is shot through with phenomenal descriptions of the natural world. His work dealt with decline and the ending of eras—John Piper once said that “Cormac McCarthy is to the American literary canon what Judges is to the biblical canon.” But there is much more to McCarthy than that, and many obituaries have falsely accused him of nihilsm. The evangelical literary scholar Karen Swallow Prior, for example, included The Road as an excellent portrayal of hope in her 2018 book On Reading Well: Finding the Good Life through Great Books.

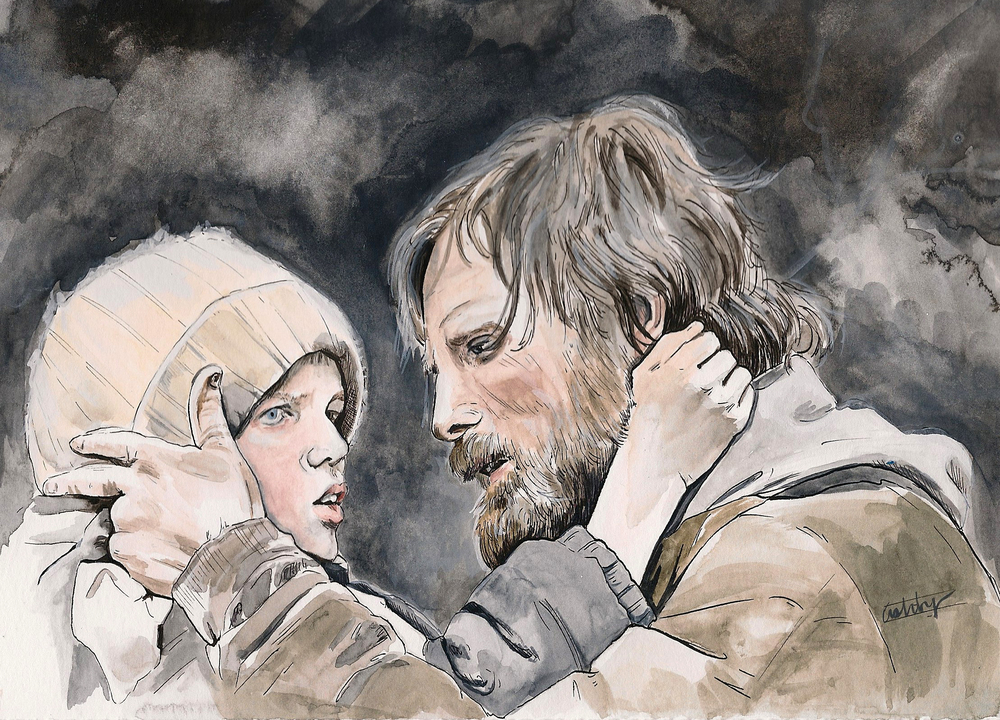

Even with the backdrop of a dying world filled with ash and evil, McCarthy’s rendering of the relationship between the father and his young son in The Road is one of the most affecting in American literature. As they travel towards the coast, avoiding gangs who have succumbed to depravity and scrounging food and supplies where they can, the father teaches his boy about preserving “the fire”–dignity, humanity, and courage. Because when nothing else is left, these things still matter:

We’re going to be okay, arent we Papa?

Yes. We are.

And nothing bad is going to happen to us.

That’s right.

Because we’re carrying the fire.

Yes. Because we’re carrying the fire.