Blog Post

The beautiful, inspiring 2,000-year history of the pro-life movement

With the U.S. Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision last year declaring that abortion is not a constitutional right, mainstream publications have hastened to present a view of the history of abortion in America today that presents the pro-life movement as a politically driven modern aberration with roots in white supremacy or other sinister ideologies. It is an attempt to distort history and delegitimize their opponents – and this strategy has been extremely effective in the past. Larry Lader’s Abortion, which was filled with disinformation, historical inaccuracies, and outright deceits, helped transform public debate on abortion and was cited several times in 1973’s Roe v. Wade decision.

There are several excellent histories that set this record straight. The Story of Abortion in America (2023) by Marvin Olasky and Leah Savas, is excellent, tracing the history of abortion in the U.S. from its beginnings, debunking the myth that it was common during colonial times, and detailing the biographies of many pro-life heroes long forgotten by history. Defenders of the Unborn: The Pro-Life Movement Before Roe v. Wade (2016) by Dr. Daniel K. Williams of the University of West Georgia is also fantastic – even the New York Times review of the book was forced to admit that medical practitioners and activists had clearly opposed abortion on human rights grounds long before the Supreme Court imposed abortion on all fifty states.

But when I am asked by pro-lifers which book they should read first to get a better understanding of the history of the movement, I always recommend a book that few seem to have heard of – perhaps because it was published so long ago: George Grant’s Third Time Around: A History of the Pro-Life Movement from the First Century to the Present. In this very readable, concise history, Grant explains that abortion and infanticide are as old as the Fall – but that since the Crucifixion, Christians have been fighting to abolish these practices. “Virtually every culture in antiquity was stained with the blood of innocent children,” Grant explained.

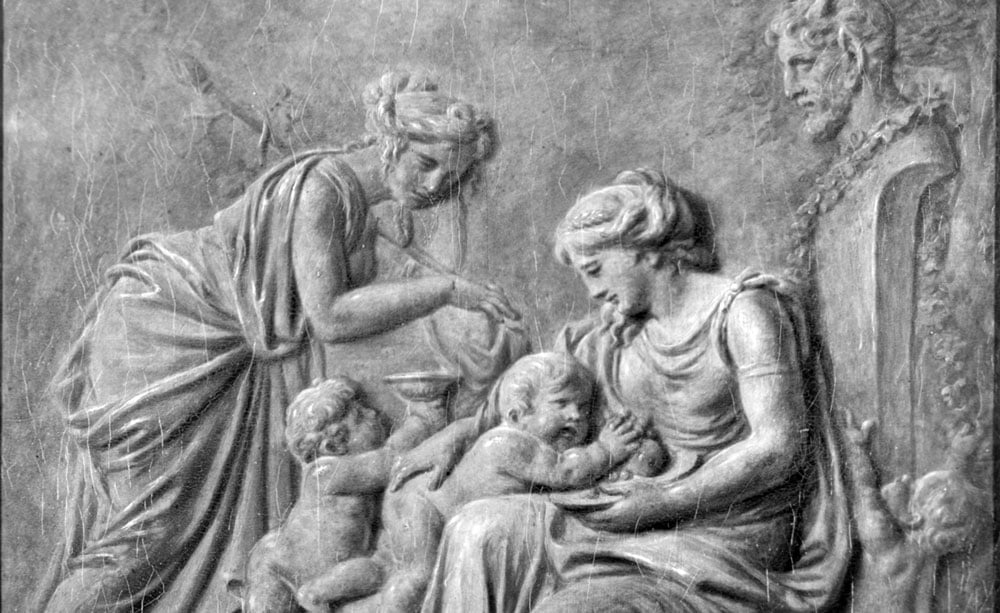

Unwanted infants in ancient Rome were abandoned outside the city walls to die from exposure to the elements or from the attacks of wild foraging beasts. Greeks often gave their pregnant women harsh doses of herbal or medicinal abortifacients. Persians developed highly sophisticated surgical curette procedures. Chinese women tied heavy ropes around their waists so excruciatingly tight that they either aborted or passed into unconsciousness. Ancient Hindus and Arabs concocted chemical pessaries – abortifacients that were pushed or pumped directly into the womb through the birth canal. Primitive Canaanites threw their children onto great flaming pyres as a sacrifice to their god Molech. Polynesians subjected their pregnant women to onerous tortures – their abdomens beaten with large stones or hot coals heaped upon their bodies. Japanese women straddled boiling cauldrons of parricidal brews. Egyptians disposed of their unwanted children by disemboweling and dismembering them shortly after birth – their collagen was then ritually harvested for the manufacture of cosmetic creams.

It was the early Church that first recognized that abortion and infanticide were wicked, cruel practices that destroyed children created in the image of God. Christian thinkers of the apostolic era condemned these practices unanimously and in the harshest of terms, from the bishop Ambrose to the apologist Tertullian to the titan Augustine of Hippo. Basil of Caesarea crusaded against a guild of abortionists he discovered in Caesarea, preaching incessantly against abortion and infanticide and going so far as to physically tear down an infanticide shrine.

In 374 AD, Emperor Valentinian responded to Basil’s war on the abortion industry by issuing a decree: “All parents must support their children conceived; those who brutalize or abandon them should be subject to the full penalty prescribed by law.” This was, Grant notes, “the first time in human history abortion, infanticide, exposure, and abandonment were made illegitimate.”

It was not only Basil of Caesarea, either. Thousands of Christians responded to the wickedness they found in society by doing everything in their power to help the weakest and most vulnerable members of their society: Addai of Edessa, Benignus of Dijon, Callistus of Rome, Alban of Verulamium, Afra of Augsburg, George of Diospolis, Barlaam of Antioch – the list goes on. As Grant writes:

The pro-life position of the early Church was not mere dogma. The patristics matched their rhetoric with reality. They worked hard and sacrificed dearly for the sake of life. In Rome, Christians rescued babies that had been abandoned on the exposure walls outside the city – often illegally and at great risk to themselves. These foundlings would then be adopted and raised up in the nurture and admonition of the Lord.

In Corinth, Christians offered charity, mercy, and refuge to temple prostitutes who had become pregnant – again, standing against the tide of community expectations. Those despised and exploited women were taken into homes where they could safely have their children and then get a fresh start on life.

In Poitiers, Christians cared for the poor, the sick, and the lame in clinics and hostels. The Church sacrificed its own personal peace and affluence by protecting and providing for those unwanted and dispossessed souls without partiality.

Clearly, Christians were not simply against child-killing. They were for life. Whenever and wherever the Gospel went out, believers emphasized the priority of good works, especially works of compassion toward the needy. For the first time in human history, hospitals were founded, orphanages were established, rescue missions were started, almshouses were built, soup kitchens were begun, shelters were endowed, charitable societies were incorporated, and relief agencies were commissioned. The hungry were fed; the naked, clothed; the homeless, sheltered; the sick, nursed; the aged, honored; the unborn, protected; and the handicapped, cherished.

Across the Western world and beyond, the early Christians introduced concepts that were at that point fundamentally foreign. Child-killing practices were so common that even the fable of the founding of Rome spoke of two children – Romulus and Remus – being left to die. Now, they were suddenly and firmly rejected and opposed. The early Christian church did more than just engage in discussion on child-killing. They engaged the culture and transformed it. For centuries, and on into the Middle Ages, Christians fought back the culture of death wherever it arose, refusing to allow it to take root, and combatting it wherever it did.

Then came the Renaissance, described by most historians as the era that bridged the medieval period and the modern era. Stretching from the fourteenth century to seventeenth century, people instinctively think of this period as an era filled with beautiful art, wonderful music, and great leaps forward in the fields of science and technology. This, of course, is true. But the Renaissance was not only a great leap forward. It was also, in many ways, a great leap backwards. The ruling classes, Grant notes, were fascinated with the pagan past of the West. Augustine and Ambrose were ignored in favor of Aristotle and Plato. With a return to pagan philosophers came a return to pagan ideas:

[The ruling classes] began to extol their pre-Christian values as well, including the values of abortion, infanticide, abandonment, and exposure. A complete reversion took place. Virtually all the great advances that the medieval era brought were lost in just a few short decades. By the middle of the epoch, as many as one out of every three children was killed or exposed in French, Italian, and Spanish cities. In Toulouse, the rate of known abandonment as a percentage of the number of recorded births varied from an approximate mean of 10 percent at the beginning of the era to a mean of about 17 percent at its end – with the final decades consistently above 20 and often passing 25 percent for the whole population of the city.In the poorer quarters of the city, the rate may have reached as high as 40 percent. In Lyons before the French Revolution, the number of cast-off, unwanted infants was approximately one-third the number of births. During the same period in Paris, children known to have been abandoned accounted for between 20 and 30 percent of all registered births. In Florence the rate ranged from a low of 14 percent of all babies to a high of just under 45 percent. In Milan, the opening of the age witnessed a rate of 16 percent. By its closing the percentage had actually risen to about 25 percent. In Madrid, the figures ranged anywhere from 14 to 26 percent, while in London, they were between 11 and 22 percent. Fragmentary evidence suggests comparable rates throughout the rest of Europe, wherever resurrected paganism was extolled.

And again, for the second time since the Crucifixion, Christians rose up to combat brutal ideologies with love and compassion. Again, they did not merely advocate a theological belief, they engaged in life-saving action. Andrew Geddes, converted under the preaching of the Scottish John Knox, sought to find and help abandoned children. Nicholas Ferrar, an English Puritan, left a London political career in 1625 to, among other things, help orphan boys with nowhere to go. Their names are many, and the lives they saved countless: Thomas of Villaneuva, Louise De Marillac, Otto Blumhardt, and John Eudes, to say nothing of titans like William Wilberforce, Thomas Clarkson, and Granville Sharp.

It is very important to take note of something here: those who value the lives of pre-born children have always valued the lives of all. Abortion advocates love to tell lazy lies about the pro-life movement – “They only care about human life before birth, not after!” they like to say. But this has never been true. Christians started orphanages, shut down abortion rings, fought against slavery, abolished infanticide, and began crisis pregnancy centres. Wherever human beings created in God’s image were threatened, it was the churches, first, who responded with compassion and assistance. As the preacher Charles Haddon Spurgeon once thundered, “The God that answers by orphanages, let Him be Lord!”

The same is true for today’s pro-life movement. As much as abortion advocates would like to claim that those fighting to expose the abortion industry and assist women in crisis only care about children in the womb, the evidence shows that nothing could be further from the truth. In the United States alone, there are more than 2,300 pregnancy resource centres serving nearly two million women every single year. Many of them, says The Witherspoon Institute, “stay at one of the 350 residential facilities for women and children operated by pro-life groups. In New York City alone, there are twenty-two centers serving 12,000 women a year. These centers provide services including pre-natal care, STI testing, STI treatment, ultrasound, childbirth classes, labor coaching, midwife services, lactation consultation, nutrition consulting, social work, abstinence education, parenting classes, material assistance, and post-abortion counseling.”

This is to say nothing of the enormous amount of charity work and financial assistance provided by churches and religious groups, which dwarf the contributions of those groups dedicated to legal abortion. The historical commitment of Christians to the welfare and dignity of all human beings – which has a 2,000-year history – continues.

Pro-lifers seeking to understand the nature of the injustice they fight and the history of the movement they are a part of should read Marvin Olasky and Daniel Williams – and they should also read George Grant. We are part of a movement with sacred origins and a beautiful history, and we walk in the footsteps of giants.

Wonderful, inspiring article