Canadian Politics, MAiD / Euthanasia

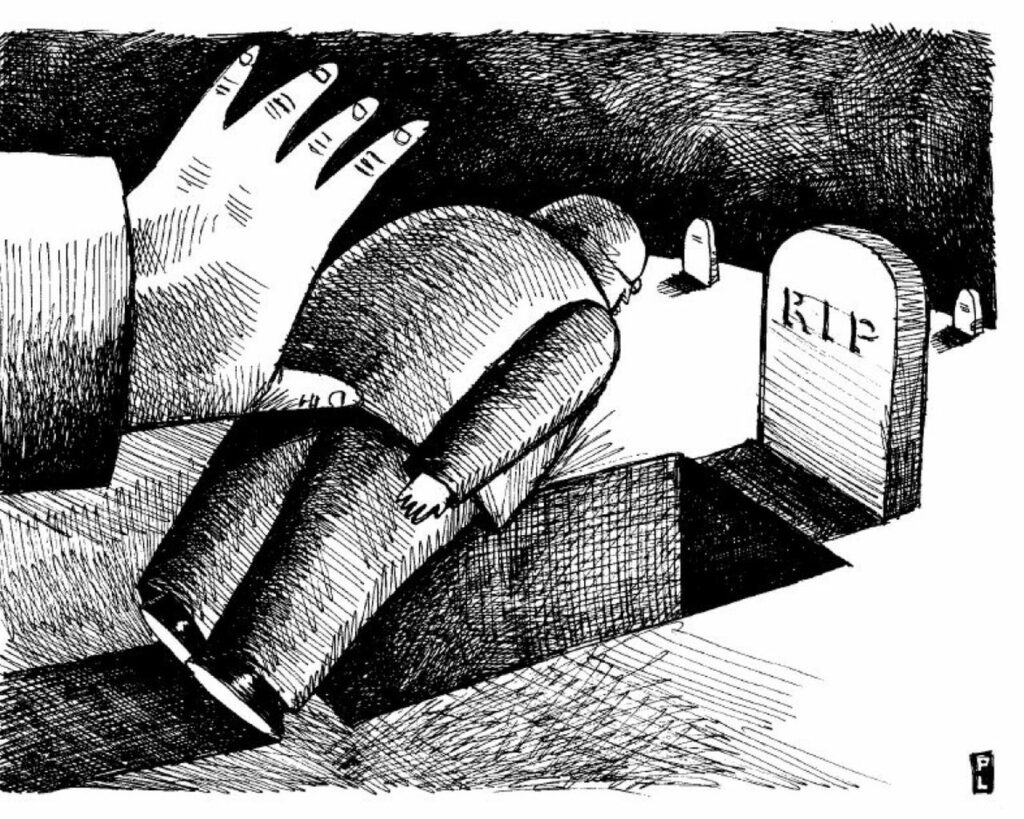

Pro-lifers were right about euthanasia in Canada. Suicide advocates were wrong.

Scarcely a week goes by in Canada without another gut-wrenching story emerging from the frontlines of our euthanasia regime.

There is Rosina, the young woman who opted for assisted suicide because of her crippling loneliness; she selected the day of her death, September 25, 2021, because it was the birthday of her ex-husband. There is the man requesting assisted suicide because he cannot get the back surgery he needs; the young mother who sees euthanasia as one of her only options because she cannot get coverage for the treatment she desperately needs; the 44-year-old Winnipeg woman who opted for euthanasia because she could not get home care.

I could cite dozens of other stories. You’ve probably read many of them yourself. The sick, sad, and isolated are being pro-actively offered assisted suicide, from veterans suffering from PTSD to a patient who was reminded by an ethicist that his medical costs were “north of $1,500 a day.” The Toronto Star, Canada’s most liberal broadsheet, referred to our euthanasia regime as “Hunger Games stye social Darwinism.”

In short: Pro-lifers were right. We warned this would happen. We laid out the consequences to anyone who would listen. But nobody did. The government plowed ahead, expanding euthanasia so dramatically that even the public has turned against their plans to sanction suicide for the mentally ill; the mainstream press, virtually without exception, championed the legalization of “MAID” as the next step in the expansion of human rights for Canadians. A few voices – in the medical community and disability community – spoke out and were ignored. They were right, too.

I mention this because the other day, a 2017 essay by Stuart Chambers in Policy Options came across my feed. Chambers, who “teaches a course on death and dying in the Interdisciplinary School of Health Sciences at the University of Ottawa,” was making the case that concerns about euthanasia and assisted suicide were nonsense. First, Chambers explains why any comparison to the Nazi T-4 euthanasia program are clearly unwarranted:

In contrast, Canada’s medical assistance in dying legislation, Bill C-14, emphasizes autonomy, compassion and personal dignity. For instance, to qualify for MAID, the individual adult in question must provide consent. Further, the person must have an incurable illness, disease or disability and be in an advanced state of irreversible decline. As well, the physical or psychological suffering must be considered intolerable from the patient’s perspective. Finally, death must be reasonably foreseeable.

Well, none of that is true anymore, is it? It turns out that we were on a slippery slope this whole time – but Chambers and his fellow suicide apologists simply didn’t see it. More:

The logic of the slippery slope does not apply to the Canadian context because, in contrast to the program of Nazi Germany, there is nothing remotely reckless about the process that led to the decriminalization of assisted suicide. After examining the evidence surrounding possible abuses, the Supreme Court of Canada in 2015 voted unanimously to strike down the ban on assisted suicide in Carter v. Canada (Attorney General).

Referencing statistics from Oregon and the Netherlands, the Supreme Court noted how ‘a system can be designed to protect the socially vulnerable.’ Furthermore, expert evidence had established that the ‘predicted abuse and disproportionate impact on vulnerable populations has not materialized’ in these jurisdictions. When discussing the efficacy of safeguards, the Court recognized that they work well in ‘protecting patients from abuse while allowing competent patients to choose the timing of their deaths.’ In other words, there is no open season on disabled people.

Therefore, comparing those who are terminally ill, who are suffering grievously and who consent to assisted suicide to those who are not terminally ill or suffering but then have a death-hastening procedure forced upon them is misleading.

Once again, since Chambers wrote this essay – which is notable because it precisely encapsulates the prevailing elite opinion on the issue at the time – Canada has become an international cautionary tale. Our system manifestly does not protect the vulnerable, which is why disability advocates are speaking with one voice to condemn this system and have gone to great lengths to explain why it poses an active danger to their lives. The “predicted abuse and disproportionate impact on vulnerable populations” has materialized in Canada, and indeed can now be read about in newspapers around the world. And vulnerable, hospitalized patients have had “a death-hastening procedure” – that’s an odd way to describe getting killed by lethal injection – pushed on them, as many Canadians have now attested.

As Canada’s euthanasia death rate surpasses four percent and we prepare to open the floodgates in 2024 by permitting suicide-by-doctor for the mentally ill, it is worth remembering that everything the euthanasia activists told us was wrong. A lot of people have died as a result, and many more will die before we finally reverse course – if we ever do.