Blog Post

The little Jewish girl who won the Nazi contest held by Joseph Goebbels to find the “perfect Aryan child”

By Jonathon Van Maren

On May 17, 1934, a beautiful little girl was born to Jewish parents in Berlin. Jacob and Pauline Levinsons, both talented professional singers, called her Hessy, and they were tremendously proud of her—despite the fact that Jewish babies were not particularly welcome in Germany at the time. A year later, the Nuremberg Laws were passed by the Nazis, shoving Jews to the fringes of society and eliminating many of their freedoms. Jacob lost his job, and had to find work as a door-to-door salesman. The Nazi party had created the framework they would utilize to inflict innumerable horrors on millions of men, women, and children just like the Levinsons.

Men like Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels dreamed fervently of a racially purified Germany, where the supposedly god-like Aryans would take their rightful place as the rulers of the human race. Jews were presented to the German population as grotesque vermin and subhuman in propaganda films, newspapers, and magazines—ant-Semitism had to be stoked from embers into flames in order to prepare the people for the bloodshed to come. Der Sturmer was one such magazine, featuring ugly caricatures of Jewish people with hook noses and evil, furtive expressions on their faces (the publisher, Julius Streicher, was convicted of crimes against humanity in 1946 at the Nuremberg Trials and hanged.)

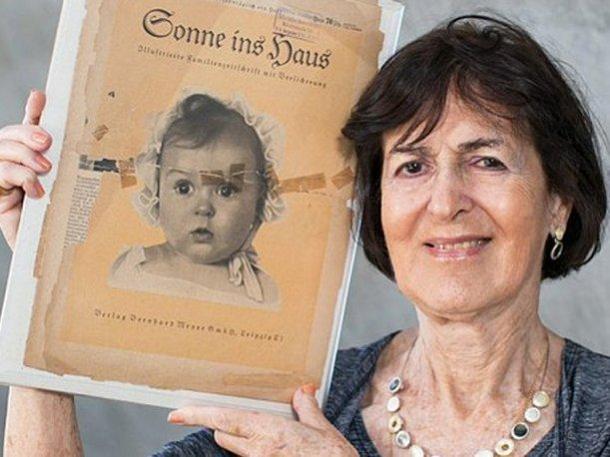

In order to contrast the supposedly inferior races with the Aryan race, the Nazi Ministry of Propaganda not only demonized the Jews and others; they promoted and idolized the men, women, and children that they considered to particularly fine examples of Aryan perfection. In 1935, the Ministry decided to host a photography contest to select an speciman of “the perfect Aryan” poster child—the photo, it was said, would be chosen personally by Joseph Goebbels himself. Ten renowned photographers were asked to submit photographs of German children who might qualify. One Berlin photographer, disgusted by the Nazi obsession with race, secretly submitted a photo of Hessy Levinsons, the little Jewish girl born to Latvian parents.

Her photo was chosen.

Hessy Levinsons Taft now works as a professor of chemistry in New York. She and her family survived after fleeing from Germany to Paris, later leaving France for Cuba before settling in the United States in 1949. Some time ago, she joined me to share the story of the Jewish girl who was chosen by Nazi Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels as an example of the perfect Aryan child.

There has been a lot of media attention focusing on your story. How did that come about?

It came about unexpectedly. The story of my baby picture on cover of a Nazi magazine was something that I had kept secret for a very long time. And in fact, if I may say so, my parents insisted that it be kept quiet for a long time. During the war it was obvious–I was too small to know about that back then. My parents kept it quiet for obvious reasons: they didn’t want it to be detected. But after the war, after we got out of Europe, my father [took] “moral lessons” from the Nazis: Among other things, that Jews should keep a low profile. Germans in Germany were successful bankers, while millions of Germans were unemployed, out of work and during recession and so they had been against Jews, when Jews were successful. So, my father made it very clear that we should never talk about it very publicly. And so it was [that] it remained a family secret for many years.

It was not until 1987 that I first spoke about this, when I had an opportunity to write a chapter in a book. The book was [about] Jewish survivors from Latvia, [as] my parents were originally from Latvia. At that point, my brother finally said well, ok. It’s time to tell the story. I did, the book was published, and shortly thereafter the US Holocaust Museum opened in Washington and I gave one copy of the original magazine as well as my only copy of the birthday card that was reprinted from it, widely circulated all over Germany [and] even in Lithuania and neighboring countries. I gave that to the Holocaust Museum and still things were fairly quiet, I guess, it still was not the time when the Internet was in full gear. This is the prelude to answering your question. Recently, I gave other valid copy that I had of the magazine to Yad Vashem in Israel. I had agreed to be interviewed by the local Israeli paper, which published only in Hebrew and I very naively thought that it would get published only in Israel. Well, apparently, I was mistaken–that paper does have an English language online version, although the print version is only in Hebrew. From there it went viral. I think Bild, the German newspaper, picked it up first, and then from there lots of other people picked it up.

It’s a story a lot of people are attracted to it because with all the horrible stories you hear coming out of the Second World War, there is sort of delicious irony in revealing how stupid anti-Semitism actually is, when you see Nazis selecting a baby photo of a Jewish girl as their optimal Aryan specimen. How did this story unfold?

My mother took me to a photographer in Berlin when I was six months old. He was a very prominent photographer. His name Hans Ballin. Shortly thereafter in 1935, my baby picture appeared on the front cover of a Nazi magazine–only Nazi magazines were allowed to publish at that time. It was a family magazine, [and] the headline over my picture said, “Sun in the House.” My parents were totally surprised that this happened. My mother rushed back to the photographer to ask what happened. He told her very quietly [to] close the door, pull the curtain, [and] took her to the back room and told her that the Ministry of Propaganda, which at the time was run by Joseph Goebbels, decided to have a baby contest to select a beautiful Aryan baby for the cover of this magazine.

So, they asked the ten best photographers throughout Germany to submit their ten best pictures. They had a hundred photographs. The photographer told my mother: I slipped your baby in with my quota of pictures. My mother said to him: You know it’s a Jewish child! And his answer is one that I always remember: [“I wanted to make the Nazis ridiculous.”] So, that’s how it happened, that photograph is still today on the piano that my father had bought for my mother at the time. I have the piano and the photograph, it’s still on the piano, the original photograph.

[As for] the magazine, my mother was able to keep three copies during the war. My parents were both opera singers–they studied at Hochschule Musik Berlin–of course my father had contracts to sing at 19 leading operas in Berlin. But it was before I was born, and his contract was cancelled when they found out that he was Jewish. But they had lots of music, so my mother carried three copies in different operatic scores.So your parents weren’t very happy when it came out?

My parents were terrified. This magazine appeared in every kiosk in Berlin, probably all over Germany. It was shown in the storefronts of stores that sell baby clothes with an announcement, “Buy beautiful clothes for your beautiful baby.” It also got reproduced as a birthday card. The photo underneath it said, “heartiest congratulations for the birthday.” So, it was sold all over the country–and in fact beyond. My aunt, who lived in Lithuania, went into a store to buy me a birthday card for my first birthday and asked the woman: Where did you get this? And she said, I got this in Berlin and it’s not a doll, it’s a real baby, it’s a Berlin baby.

So she quietly bought the card and sent to us inside an envelope. The consequence of all this was that I could no longer be taken to play in the park. My dear aunt Masha, who always took me to the zoo, which apparently was my favorite then—[that] also had to be cancelled. I couldn’t go to the zoo. I went outside just wheeled in a carriage, always moving and never stopping for anyone to talk to me for fear of being recognized. Particularly after I was one year old, [because] eventually I learnt to say my name. My maiden name was Hessy Levinsons. Let me assure you, if anyone would have found out my real name, I wouldn’t be talking to you today.

So how did your family navigate the war in Germany?

There was another very scary incident that happened to my father, I should [mention that] my sister was born in end of 1936. And in early 1937, my father had a very scary incident. He was arrested in his business. After his [opera] contract was cancelled, he set up a very successful import and export business. And he had, by luck, an accountant working with him, who came periodically to the office to work on the finances. One day he was arrested, while the accountant was there. This accountant was a card-carrying Nazi, and when they arrested my father, the accountant pulled the typical Hollywood-type trick: he followed the agent and got into a car and said follow that car, which ended up in the police station. The accountant barged through all the gates security and barged into the room where they were interrogating my father and he yelled out Heil Hitler! And they let him in, listened to him, and he said that he would vouch for this man. I think they trumped up some charge of tax evasion, that made no sense.

Whatever it was, he was released as a result of this. So my parents decided that it was really time to leave Germany, [as] things were getting very bad. They noticed how many Germans were out of work. I must say, my parents had gone earlier, this was before or after, probably after, my baby picture. They went to see the Latvian consul. It was before my birth because the Latvian consul said don’t worry about leaving Germany, it’s country where every little town has an opera house, you are better off here. I will tell you when it is the time to leave, when I leave, you should leave. My parents decided that they would leave on their own, so they left. We went for several months to Latvia to just visit family. Then my father got a setup in Paris, so we moved to France in 1938.

In 1938. So what happened when the Germans occupied France?

Well, that’s very interesting. I can tell you another episode of what happened to me with regards to the baby picture. In France, I developed an [illness]. In those days, it was common for the doctors to make house calls. So, this doctor came to the house and made some comment about me being a cute kid, and my mother promptly told him the story of the cover girl baby. And this doctor was Jewish; he immediately said oh my word! Let me take this story to Paris, I have a friend who is an editor of a newspaper. If we could blast this out publicly, we would ridicule the Nazi philosophy and then show a clear example of the stupidity and folly of their ideology. My mother was ready to let him have this magazine, to print out the story. My father refused: he said we were not going to make it public. There are too many German sympathizers in France, and it would be a great effort to dispel their ideology. The doctor then said to my father, “You have nothing to fear now, you are in France”.

Of course, history has proved my father right. It was tough for us in France. We were told never to speak German in street. But speaking German was natural for my sister and me, particularly [because] we had brought with us from Germany a German nanny. She was trained as a nurse and my parents felt that they couldn’t leave her, a young Jewish girl, in Germany. So, she came with us, but she was notorious [for not] learning any other language. So, we continued to speak German with her. She lived with us, so it was natural for us to speak German on the streets, and it was very dangerous to do that. One time my sister and I almost fell into a trap, taking chocolates from very nice soldier, we thought, who was speaking German to us until we caught ourselves and ran away. It got very difficult for us. I was very unhappy at school, I had no friends, and I don’t know why but I think it must be related to the fact that I spoke German. Life was very dreary, at some point.

But Paris was still Paris, so there were lots of wonderful things that could be done, in the beginning before the Germans started shutting Jews out of everything. This was the time when Jews had to wear yellow star, so that was not an issue. Nazis did come to our apartment looking for us one day. It turns out that my father had a very good childhood friend called George, who also lived in Paris. My father mentioned that we would go and visit George, [and] several hours [later] George gets a phone call that Germans have been looking for us. That was the end of our nice apartment.

But from then on, my mother, sister and I went on to Bordeaux, and my father stayed with Mr. George, sleeping on the sofa. And he very courageously went back to our apartment, fortunately, he was not caught. There were packers coming and packing things up. In particular, there were some things that were of particular value to us. My grandfather had been both a carpenter and a painter, a very good painter. My mother only had three paintings from him that were very valuable to her, and of course there was the piano that my father had given to my mother when I was born. So anyways, he decided to pack things up and eventually manage to empty everything out and send it to Portugal, where it was stored throughout the war and it stayed there well after the war, until we moved to New York.

I should tell you one interesting event that happened in 1939, the summer of 1939, before France fell. My mother wanted very much to go back to Latvia for her mother to see the grand-children, in other words, see my sister and me. I always remember this story as one of the big arguments that my parents had: it was a huge argument in Paris. My mother wanted to go back, and my father said you can’t go, you have to travel through Germany, it’s dangerous. My mother said, I am not talking to anybody, I am not going to get involved, and just be with children. My father said, you may be stopped and asked questions and someone may even ask if you are Jewish–you can’t go and back and forth! And eventually, my father prevailed. Thank God! Because every one of my family members who was caught on the other side of Germany after September 1, 1939 was killed. I had one aunt, my mother’s oldest sister, who had left Latvia long before–she was considerably older–when she married she had moved to Leningrad, her descendants are now living in Israel. But everyone who was in Latvia after September 1, 1939 was murdered.

Your whole story is a unique and compelling one. What do you want everyone to take away from your story?

I think the most important thing to me is that prejudice against Jews has long existed and is unfounded. The Nazi ideology that treated Jews as sub-humans chose a Jewish kid to represent them. I think the main thing is that anti-Semitism is ill founded, perverse, [and] it should be countered where-ever possible. I am telling my story now after many years of silence as a way to expose the folly that existed and make one small contribution towards erasing the prejudice. I feel a sense of satisfaction, a little sense of revenge, that I am alive and can tell the story. And I of course belong to the group of people who would say never again, with a very anxious fear that in fact, God forbid, things can go out of control.