Blog Post

How the last great Christian social reform movement of the 20th century defeated segregation

By Jonathon Van Maren

My introduction to this series on the 20th century, “The Century that Changed Everything,” can be found here. Part I is “The World Before the War”. Part II, “How the Great War transformed Western civilization–and is still with us today,” can be found here. Part III, “The Second World War: Saving Christian civilization from Hitler’s Reich,” can be found here. Part IV, “The Shoah: The murdered multitudes and the righteous few,” can be found here. Part V, “An eyewitness to the birth of Israel and the Convoy of 35 speaks,” can be found here. Part VI, “America versus the Evil Empire, can be found here. Part VII, “Vietnam: The War that transformed America,” can be found here. This is the eighth installment in the series.

The cultural revolution that exploded across America and traveled around the world during the 1960s and ‘70s was, for the most part, both sexual and secular. The feminists, the hippies, and the nascent LGBT movement united by anti-war sentiment and backed by the pulsating beat of rock and roll overturned norms, trashed institutions, and insisted that America and Christianity had gotten everything wrong. America could not be reformed, the new Left insisted. America needed a revolution, and a revolution meant that the values America had been founded on needed to be totally rejected.

There was one exception to all of this. As revolutionaries took to the streets from Washington, D.C. to Montgomery, Alabama, one movement was singing different tunes—and those tunes sounded very much like hymns. Unlike those declaring that America needed to be destroyed, these marchers were calling on Americans to recognize that there were systems of injustice in place that defied the American Constitution and violated the principles of Christianity. America needed to change, these reformers declared, not because America was irredeemable, but because America was not being true to her own values. The civil rights movement would become one of America’s last major Christian social reform movements, and they would transform the nation in less than a decade.

***

While the budding civil rights movement had gained a few victories by 1955—the most prominent of which was the Brown v. Board of Education decision at the Supreme Court the previous year—segregation was still the norm across the American South. Lynching was not uncommon, and white perpetrators were almost never convicted of murdering black Americans in Southern courts. To sit on a jury, you had to be registered to vote. In most places, African Americans were barred from registering. The system was self-perpetuating, and African Americans were essentially second-class citizens, subject to discrimination of every kind. Education was segregated and sub-standard. Voting was impossible for many. African Americans had no voice in their own country. For many white Southerners, segregation was the way their forefathers had lived, and they would live that way, too—no matter what the cost.

As I described in detail in my 2017 book Seeing is Believing: Why Our Culture Must Face the Victims of Abortion, it was the funeral of a 14-year-old boy named Emmett Till that provided the catalyst for a movement that had previously consisted of sporadic protests and litigation by the NAACP. Till was accused of “talking fresh” to a white woman while visiting his cousins in Money, Mississippi, and was abducted and murdered by two of her relatives in retaliation. When his coffin arrived in Chicago, his mother decided to have an open casket funeral. Tens of thousands saw his mangled corpse, which some said could be smelled blocks away. His killers were acquitted and sold their story to Look magazine shortly thereafter. Jet Magazine published a photo of his battered face, and a young woman named Rosa Parks was so upset by the photo that barely four months later, on December 1, 1955, she refused to give up her bus seat to a white man in Montgomery, Alabama.

Rosa Parks’ lone act of defiance soon developed into a full-blown campaign. In response to her arrest, the Women’s Political Council organized a bus boycott. On day one, the boycott was an enormous success. That night, a huge meeting was held at a local Baptist church, and community members voted to continue the boycott. The keynote speaker was a fresh-faced 26-year-old preacher, Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. If you listen to that first speech—on December 5, 1955—you can already hear the orator he would become. King was as good that day as he would be in Washington almost ten years later, telling a massive crowd gathered in front of the Lincoln Memorial that he had a dream. People not only heard what he said, they felt it. He was a new leader for a new movement, a spontaneous combustion of fury and justice—armed with nonviolence. From his very first speech, he was destined to be the voice of the new movement for justice and against segregation.

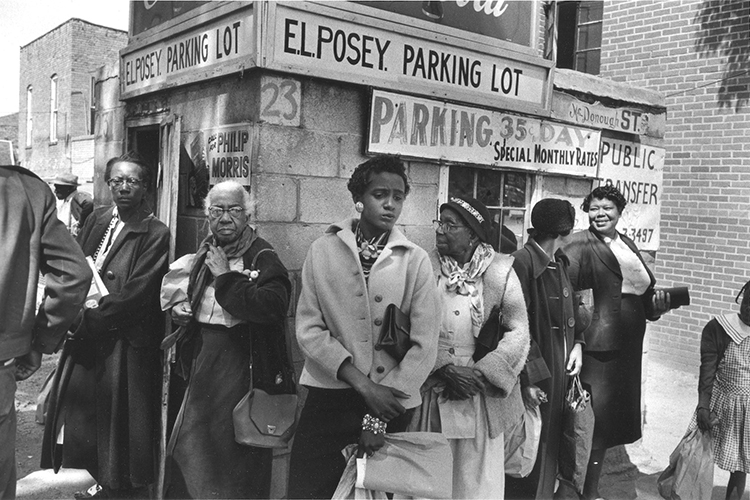

Before the boycotts, nearly two thirds of those who rode the bus in Montgomery were black. After the boycott began, they walked, or carpooled. Bombs were tossed into King’s home—it is staggering to consider that he carried on for more than a decade after experiencing near-deadly violence right from the outset. Nightly mass meetings were held in church, with hours of prayer, hymns, and spirituals. Rev. Ralph Abernathy would later remember that the fear left them when they were together in church. The white opposition was furious, and black leaders were indicted for violating anti-boycott laws, attracting national attention. King took the spotlight. Not for the first time, the segregationists soon realized the danger of taking local issues national, where the civil rights cause could win in the court of public opinion. A year later, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the boycotters. The victory, one activist said, made her feel as if “America was a great country, and we were going to do more to make it greater.” It was their country, too.

In retrospect, it is difficult to understand the backlash of the segregationists. The Klan greeted the rising movement by warning of a “mongrel nation.” White politicians declared that segregation would be preserved “in the name of God” and even blasphemously hoisted their Bibles in defence of racism on live TV. And the mobs that gathered to prevent black students from attending previously all-white educational institutions were particularly chilling. When Autherine Lucy was admitted to the University of Alabama, a white crowd responded, chanting “two four six eight we don’t want to integrate.” Violence bubbled below the surface, and there was ample historical precedent for it. White politicians pushing back against integration insisted that these things had to be done gradually, with one lawyer responding by stating that “ninety years since the Emancipation Proclamation seems gradual enough.” Lucy won in the courts, but the university promptly expelled her for pointing out that riots had been used to prevent her attendance.

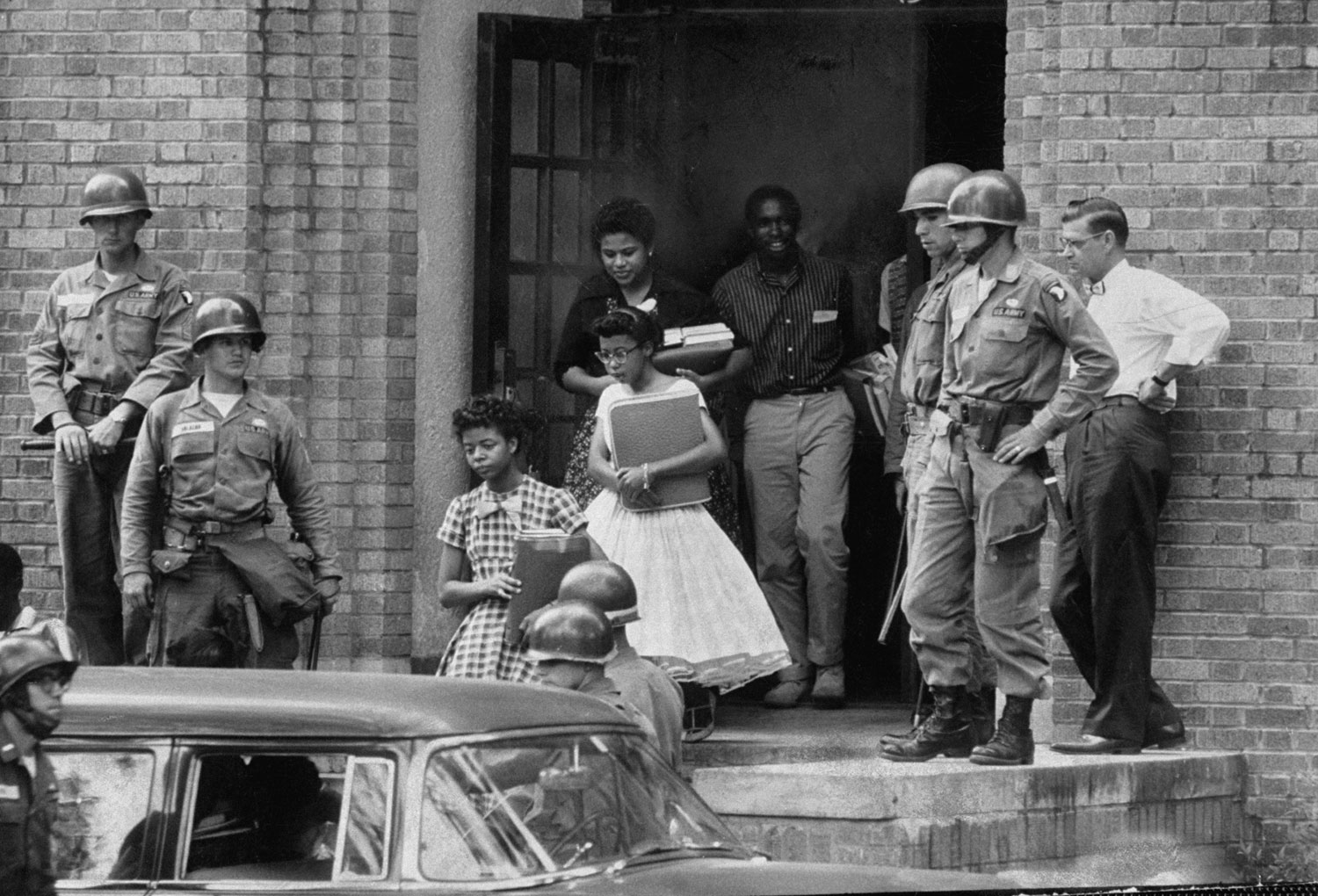

It is interesting to note that many conservatives and white Christians at the time stated that they agreed with the aims of the civil rights movement but disagreed with the use of nonviolent direct action—and any activism perceived as breaking the law. This ignores the fact that from the very beginning, it was the segregationists who were defying federal law. In 1957 in Little Rock, Arkansas, nine black students were to be admitted to Central High in accordance with Brown v. Board of Education, which mandated the desegregation of schools. In defiance of federal law, the governor ringed the school with armed national guardsmen and ordered them only to admit white students, risking open conflict with the federal government and emboldening white mobs who descended on the school, screaming obscenities. The national guard turned the black students back. (Watching footage of the mob, I was reminded of Dr. Jordan Peterson’s admonition that we should always view history from the perspective of the perpetrators: They did this right in front of the cameras, for the nation and the world to see, and for history to judge. That is how right they believed themselves to be.)

The mob soon turned violent, and President Eisenhower—the World War II general who had deployed troops against the Nazis–had to send in the paratroopers of the 101st Airborne Division to protect the teenage students from white citizens with guns and bayonets. Each student had a personal soldier posted outside the classroom, walking them from class to class. But the segregationists still fought integration tooth and nail. Many governors chose to close down schools rather than integrate. It was not the last time that a president of the United States would be forced to intervene.

***

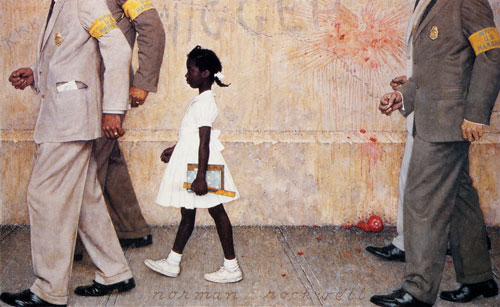

As integration battles played out across the United States, one story would eventually come to symbolize them all—that of a little girl named Ruby Bridges, immortalized in a Normal Rockwell painting calmly walking to school past racist graffiti. I reached her by phone to ask her what that experience was like all those years ago, and although she didn’t realize the full significance of what she was doing at the time, her memories are still sharp and clear.

“On November 4, 1960, the public school system here in New Orleans was desegregated,” Bridges told me. “I was one of four six-year-old girls chosen to desegregate two public schools in New Orleans. Three girls attended one school together, and I attended William Frantz Elementary alone. I was escorted by federal marshals every day. They drove me to and from school and escorted me into the building and stayed outside my classroom all day for a year. I spent every day in an empty classroom with a single teacher that came from Boston to New Orleans to teach me because lots of teachers quit their jobs. They didn’t want to teach black kids. The first day of school, when I was being escorted into the building, I sat in the principal’s office all day because all the people outside the school rushed inside and went into every classroom and pulled out every child. Over 500 kids withdrew from school the very day I entered the building.”

Ruby Bridges, an innocent and adorable six-year-old, found it all hard to understand at first. “I’m from New Orleans so I’m accustomed to Mardi Gras,” she said with a laugh. “Growing up in that environment, the first day of school when I turned the corner and saw mobs of people outside of my school and police officers everywhere, I actually thought we’d stumbled onto a parade. I went to school every day and I was in this empty classroom, but I knew kids were supposed to be in school. Little did I know that there were maybe five or six white kids, and their parents had to cross the same mob every day to get them in the building.”

“The principal would hide those kids so they would never see me and I would never see them,” she went on. “The whole year was very, very lonely for me, and I didn’t realize that there were a few kids stashed away in the building. I could hear them, but I could never see them. Eventually my teacher went to the principal and threatened to report her to the superintendent for hiding those children, so I was brought to where those kids were and a little boy said to me, ‘I can’t play with you because you’re a nigger.’ Once he said that, all the pieces kind of came together for me. I realized it was about me and the color of my skin, and I realized why all the people were out there. It took awhile, but finally I understood what it was all about.”

Every day, protestors showed up to show their disapproval of the little girl’s presence, arriving on buses and marching back and forth in front of the school. “Even though I had federal marshals, there were times when they would bring a small coffin, and inside was this black doll that they dressed up and put in the coffin,” Bridges told me. “I used to have nightmares about it. My mom would say: If I’m not with you and you’re afraid, you can always say your prayers. All those people are crazy and need praying for. So I would say my prayers before school and after school, and if I forgot to say them, I would go back and say my prayers. I think even then, although I wasn’t aware of it, I so believed in prayer. It was building my faith. I didn’t know it then, but at 60 years old, I absolutely stand on my faith and believe in the power of prayer. I can honestly say to you that that was what really helped me form those beliefs and made it easy to get past the mob and inside the building.”

It was hard on her parents, too. They were sharecroppers from Mississippi who hadn’t been allowed to attend school when they were needed in the fields—her mother had an 8th grade education, and her father had only made it to 6th grade. They weren’t activists, but they badly wanted Ruby—who had five siblings at six years old—to receive the education they had not. That said, they had no idea what the cost of becoming the epicentre of a civil rights battle would be. When the NAACP visited them and pitched the plan, they warned of repercussions and mentioned that federal marshals might be necessary, but the ramifications went far beyond that.

“My father was fired from his job,” Bridges told me. “He was a service station attendant and worked on cars. His boss told him that all his customers knew that it was his daughter going to this white school, so they let him go. You couldn’t come onto the street we lived on—it was blocked off and monitored by federal marshals. They got lots of bomb threats. I don’t think they expected that at all. It was really hard for my father—he was really against sending me to that school. My mother convinced him. Most fathers want to protect their children. My father had also been to war. He’d fought in the Korean War and said you could go to war and fight on the frontlines, but if you were black, you were just a colored soldier. You couldn’t go back to the same barracks; you couldn’t eat in the same mess hall; you were still separated, even at war, fighting for the same country. So he was against it, and the NAACP advised him not to escort me to school—that my mother should do it—because they thought it would be hard for a father to restrain himself if they were actually threatening me.”

It was Ruby’s teacher that got her through the year. “Barbara came from Boston to New Orleans because her husband was in the military, stationed in the South,” she explained. “She was accustomed to teaching different nationalities because she’d taught on military bases. She was not a prejudiced person; she didn’t care what I looked like, so she took the job. She said it was a love story for her—she fell in love the moment she laid eyes on me as a child. We were in that classroom and in our own world, and it had nothing to do with the hatred going on outside. My experience was very different from that of the other three girls who were integrated at the other school, because they didn’t have my teacher. Love can prevail over hatred.”

After that year, the ordeal wasn’t discussed in New Orleans. Ruby’s parents divorced when she was in seventh grade, and she grew up poor. “I knew there was something better outside my community, but I didn’t have access to it.” She didn’t realize that she was the subject of a Norman Rockwell painting until she was 18 and a reporter told her, and that was when she realized that her experience had not been something that just happened in her neighborhood—it had been something the world watched. She became a travel counselor, which allowed her to travel; something she’d always wanted to do. “The world was much bigger than the Ninth Ward, New Orleans,” she told me. But what happened there had been part of changing the world all the same.

***

The fight to desegregate schools and universities often exploded into violence. At the Ole Miss riot of September 30, 1962 (also know as the Battle of Oxford), a segregationist mob erupted on campus over the admission of James Meredith. Federal marshals were shot, and an Oxford worker and a French journalist were killed. There was smoke, gunfire, and burning cars, followed by U.S. Army jeeps rolling up with troops in gas masks, wielding rifles. One commentator called it the last battle of the Civil War, and it proved that the rioters may not have been willing to die for segregation, but they were certainly willing to kill for it. Three thousand troops were called in to quell the mob, and two days later, federal marshals escorted Meredith onto campus. The segregationists were losing.

It was segregation on campus that first attracted the attention of James Zwerg, a white student who would become an icon of the civil rights movement. In 1960, Zwerg attended Beloit College, studying sociology. His roommate, Robert Carter, was an African American, and Zwerg noticed that he was frequently subjected to awful treatment. Zwerg grew irritated by the fact that Carter never responded in kind, and finally chewed him out, demanding to know why he didn’t stick up for himself. Carter walked over to his dresser, pulled out a copy of King’s Stride Towards Freedom, and told him to read it. It was the story of the Montgomery bus boycotts and outlined the six principles of non-violence and the six steps necessary for social change. Zwerg was intrigued.

***

I reached Zwerg by phone at his home in New Mexico—he is now 80 years old. All these years later, he is still a phenomenal storyteller.

“Out school had six Negro students, five fellows and one gal,” Zwerg told me. “I saw that when we went into town, there would be situations where the barber wouldn’t cut Bob’s hair. In fact, the first night my folks took the three of us out for dinner. We ordered and were sitting there and sitting there, and finally someone came up and whispered in my dad’s ear. He looked quite upset and said: We’re leaving. As we left, he apologized to Bob. They refused to serve him.”

In January 1961, Zwerg participated in a one-semester student exchange program to Nashville’s Fisk University, a largely black school and a hub of civil rights activism. He soon met the 21-year-old John Lewis (who was several months younger than Zwerg), one of the leaders of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), a student civil rights group utilizing the tactics of nonviolent direct action. After witnessing more instances of segregation, Zwerg talked things over with Lewis. “As we talked, the strength and faith he exuded, the absolute commitment to nonviolence just intrigued me,” Zwerg recalled. “He invited me to come that following Wednesday to a workshop on nonviolence. I went and observed, and that was kind of my beginning. I felt that I wanted to do something. I helped one of the fellas start a newsletter that we would put together and distributed to the various schools talking about upcoming demonstrations.”

“A workshop was kind of two parts. One part was almost like a church service, with the freedom songs and testimonies of how nonviolence had touched their lives or changed their lives; Scripture readings; philosophical discussions of the principles of nonviolence; discussions of potential for violence and what actions might be taken to negate it or eliminate it during a demonstration. And then there was the hardcore workshop where those kids who wanted (or thought they wanted) to demonstrate would be tested. It was very severe role-playing. They literally spit on them, kicked them, hit them, blew smoke in their face, used every foul, derogatory name they could.” The instructor was Jim Lawson, “who was exceptional in that he was a seminary student at Vanderbilt and was expelled because of his anti-Vietnam War activities and spent 14 months in jail being a conscientious objector. He’d then gone and spent four years in India studying Ghandi and nonviolence, and in 1958 King asked him to go to Nashville.”

Lawson taught his proteges that nonviolence was “a way of life for courageous people”—if it was just a “light switch you turned on or off, sooner or later you’d encounter a situation where the violence would become so intense you’d break. He was an exceptional leader. He would demonstrate right with you.” Zwerg found the workshops incredibly persuasive. “I grew up in a church and I thought I was a Christian, but some of the challenges he had were really remarkable,” Zwerg told me. “It finally hit me one day that for me, as a Christian, the Gospels—the story of Jesus—was really the most powerful story of non-violent direct action ever written. Jesus embodied all those principles of non-violence: Love for your enemy, forgiveness, innocent suffering, attempt to educate—it was all there. It just hit me, and I decided I would embrace nonviolence and that I wanted to actively take part in the workshops.”

He took the training, and “was surprised to find that I did not lash out, verbally or physically. I reached the point where they said: Jim, you’re ready. Will you demonstrate?” Zwerg agreed, and the very first time he walked into a theatre lobby with a black demonstrator, he was knocked out cold and tossed onto the pavement. For a time, he was the only white student in Nashville participating in the demonstrations. Whites were almost always the focus of violence, but the deeper Zwerg got involved, he told me, “the deeper your faith became, the deeper your commitment became. There was such a powerful bond between the students. We knew each other. If you were going to encounter violence, you know that every other student there was giving you their strength, so you were able to take so much more than you would have been able to individually. Over the months, it was recognized that my commitment was deepening and my faith was deepening, and we knew that there was a power that was working in us and through us—we felt that very, very strongly—and I was selected to become a member of the Central Committee.”

Zwerg, along with Dianne Nash, Bernard Lafayette, and John Lewis would go and speak with out-of-town students to get them interested in the struggle. They often met in a Baptist church, and the pastor, Rev. Kelly Miller Smith, was one of their mentors (Zwerg referred to him as “kind of the Dr. King of Nashville—a wonderful man.”) “One of the things that’s often overlooked is where did we meet? In churches,” Zwerg reminded me. “Who were our adult advisors? Ordained clergymen. Ultimately it grew beyond the Christian, but it was the Judeo-Christian background first. Most of these kids were probably Baptist.”

In 1961, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) began to organize the Freedom Rides. The first, departing from Washington, DC, intended to challenge white-only lunch counters across the South. One of the buses was ambushed and attacked in Anniston, Alabama, and Bobby Kennedy sent a representative to talk them into going home. “When we heard that, we were extremely alarmed,” Zwerg told me. “Our view was that that gave the impression to the segregationists that all they had to do was become violent enough and we’d turn tail and run. If that was the impression left, it could set back the movement years, if not decades. Our immediate decision was that the ride had to be continued, and we were the logical ones to do it. We’d successfully integrated the movie theatres; we did not have a new campaign planned at that point. The biggest thing was coming up with the logistics.”

It only took a matter of hours to come up with the money. James Farmer and Martin Luther King Jr. were very opposed to the plans, warning the students that they could be killed. They understood that. “It was reiterated over and over and over again—probably 14 of the 18 students volunteered to go—that you needed to understand that you were going to get arrested, beaten, or killed,” Zwerg said. “You needed to realize what you were putting on the line. We were leaving during finals week, so we were going to miss our finals, which would have an impact if we lived through it. All of us were recommended to go back and talk to our teachers and the dean of students to see if we could take finals later if we lived through it. Dianne suggested that the ten of us who were selected to go on that first ride should write some note to our loved ones and leave them with her in the event that we were killed.”

“Then it was just a matter of getting on the bus.”

Zwerg and Paul Brooks were arrested by Bull Connors outside the city limits of Birmingham, with the rest of the riders getting taken into “protective custody” and dumped at the state line. “We spent two and a half days in the Birmingham jail before went to court,” Zwerg recalled. “At that point the judge had learned that Greyhound was going to take us to Montgomery, so our sentences were passed over. It was going to be three months and a fifty dollar fine, as I recall. He told us to get on the bus and get out of town. We went to Rev. Shuttlesworth’s and were able to shower and clean up a bit, and then went back down to the bus station. The second group from Nashville, with Bernard Lafayette as the spokesman, joined us. So instead of 10 we were at 21 students. We sat in the bus terminal that night with the Klan marching out front in their hoods, and the next morning got on the bus for Montgomery.”

The rest of the trip was supposed to be easier. Alabama safety commissioner Floyd Mann had guaranteed the riders protection to Montgomery, and the police commissioner there had promised that he would provide protection upon arrival. This turned out to be a lie. “He told the Klan that they’d have thirty minutes before any police would show up. We did have full protection all the way to Montgomery, so it was a relaxing trip. Alabama was beautiful. It was mid-May; everything was turning green; flowers were starting to bloom. The bus driver put the pedal to the metal so we were just flying down the freeway. When we hit Montgomery, we realized the protection was gone. The closer we got to the bus terminal, within a couple of blocks, we realized that there was no vehicular traffic. We didn’t see any pedestrians walking around. As we pulled into the terminal, we noticed a squad car pulling out. I remember John Lewis said something like: That’s not good. That’s not a good sign.”

The riders were expecting to meet members of Ralph Abernathy’s congregation at the terminal, but when they exited the bus, all was eerily quiet. “There were a few press people there; John was our spokesman,” Zwerg told me. “As he approached the microphone, this one fellow went at the media. He grabbed a parabolic mic, threw it to the ground, and stomped on it. Then he went at one of the photographers and was trying to grab his cameras, threw him to the ground, and kicked at him. That seemed to be the cue. Around the bus bays and up the driveways came the mob, screaming: Get ‘em, get ‘em, kill ‘em, get the niggers. You could see the weapons they were carrying and the hatred on their faces. We knew were in for a beating. I bowed my head and asked God to be with me and give me the strength to remain nonviolent and to forgive them. I encountered the most incredible religious experience of my life, because I did indeed feel a presence. I don’t really know how to express it. I was surrounded by this incredible love and peace. I knew in that instant whether I lived or died, it was going to be okay. And then I got beat up.”

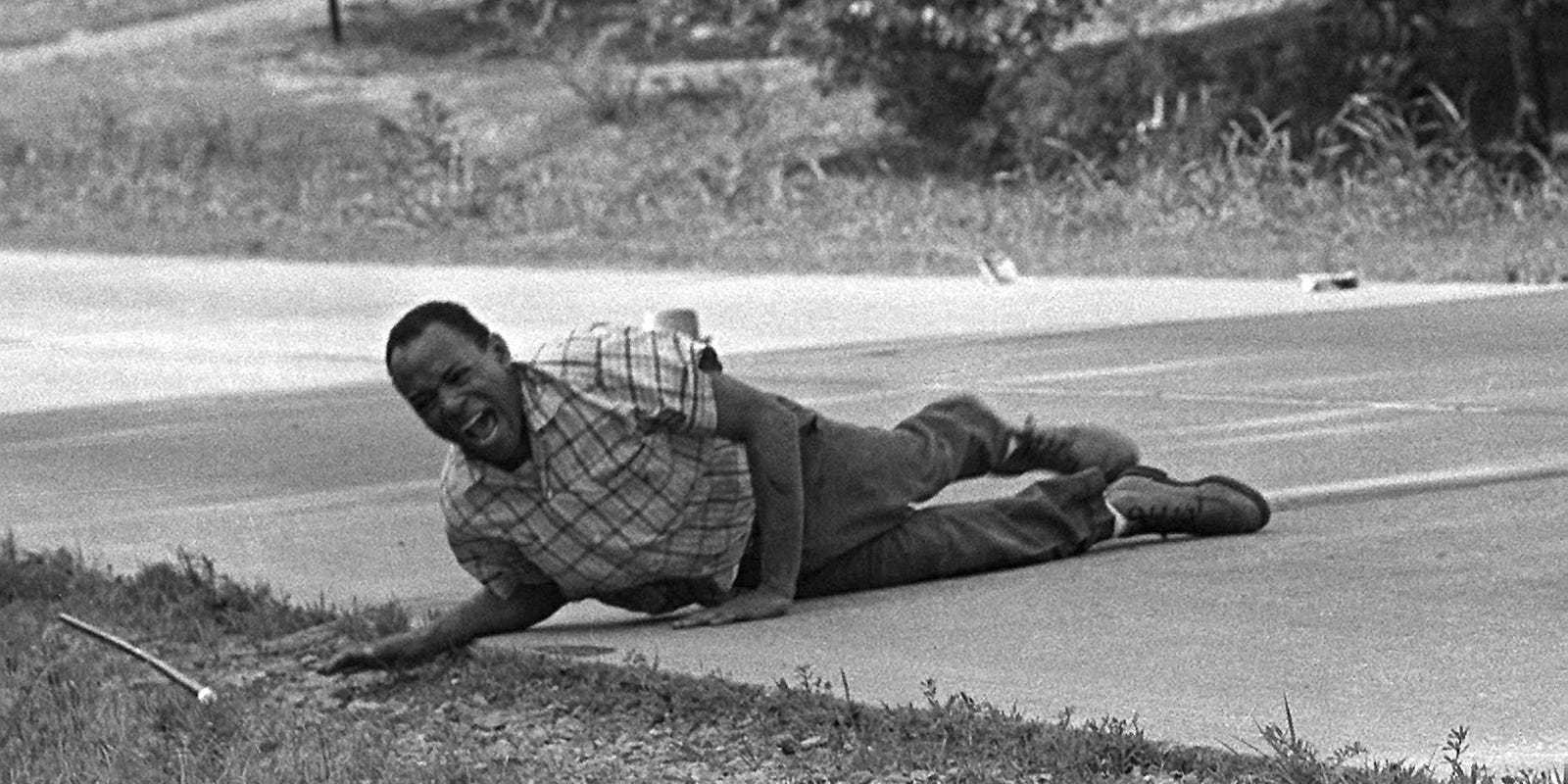

The scene that unfolded at the Montgomery bus terminal was something out of a nightmare. “It was the Klan,” Zwerg said. “The gals were able to get to taxis. One of the African American gals said that as they were pulling out, she looked back and saw that two guys were holding me and women were kicking me in the groin and mothers were holding their children up to scratch my face. Luckily I was rendered unconscious quite quickly. When I was grabbed they pulled me over a railing and I fell to the ground on all fours. That’s when I got kicked in the spine and my vertebrae were cracked. I flew over, fell on my back, and a boot came down on my face. That’s the last thing I remember until I woke up briefly sitting I the back of a vehicle. John was there and he handed me his handkerchief to wipe off blood. Then I was out again. I woke up briefly in the hospital, and then I didn’t wake up for about two days.”

During his brief stint of consciousness, James Zwerg did an interview from his hospital bed. “Segregation must be stopped,” he said, his face battered and swollen. “It must be broken down. Those of us on the Freedom Ride will continue…We’re dedicated to this, we’ll take hitting, we’ll take beating. We’re willing to accept death. But we’re going to keep coming until we can ride from anywhere in the South to any place else in the South…as American citizens.” He told me that he has no memory of the interview, and only vaguely remembers some bright lights. “There was nothing particularly heroic in what I did,” he said later. “If you want to talk about heroism, consider the black man who probably saved my life. This man in coveralls, just off of work, happened to walk by as my beating was going on and said ‘Stop beating that kid. If you want to beat someone, beat me.’ And they did. He was still unconscious when I left the hospital. I don’t know if he lived or died.”

For years, Zwerg thought he’d been taken to the hospital by a black pastor, but was told by a white fellow in Montgomery at the 50th anniversary Freedom Ride reunion that it had actually been him. “The white ambulances refused to take me and the black ambulances were scared to take me,” he explained. “So I basically laid on the tarmac for about a half hour. Then [Safety Commissioner] Floyd Mann went up to [this fellow] and said: Where are you parked? He said where it was, and Floyd said: Bring your car around.” Zwerg was loaded into the car and taken to the hospital. The photos of his battered face and the footage of his interview traveled around the world.

“I had a cousin in Russia at the time, the head of the conservatory of music in my hometown, and he was over there inspecting old organs in the various cathedrals,” Zwerg recalled, laughing. “He was riding the train and there was this Russian sitting next to him reading the paper, and he started going on about the Americans. He pointed to his picture, and my cousin looked: It’s my cousin! He said he couldn’t buy himself a drink for the next week.” His parents, on the other hand, were stunned. They had known what their son was up to—Zwerg had told them. But they had not expected him to be nearly murdered in broad daylight. Even a federal agent who had tried to protect the riders had been knocked out with a lead pipe.

“That September after the ride, I went home,” Zwerg recalled. “Our associate minister flew down and rode home with me. I had an initial two weeks there, to see my parents so they could see I was still alive. Fisk had agreed to let me come back and take finals. My brother drove me down. I was really wrestling with the situation. At that point I wasn’t aware of the broken vertebrae, all I knew was that I had severe back pain.” For the entire drive, he had to keep the seat flat. Walking to an exam, he passed out from the pain. Students carried him to the nearby medical school, where x-rays revealed his broken back.

Later that month, he received the Freedom Award from Dr. King in Nashville, and spent a half hour speaking with him alone. King advised him to continue his education: “Keep preaching that message of love and nonviolence.” But still, it was incredibly difficult to decompress from it all. “It was a mountaintop experience,” he told me. “An incredible bond formed between the students. The love we shared, the commitment we shared. During those months—I have never been so spiritually alive. I was never so certain that I was doing what God wanted me to do with my life at that time. Prayer had become so meaningful, and the reading of Scripture took on such a significance and gave such comfort and encouragement.”

He went on to seminary, got married, and served as a pastor for a time in Wisconsin. He retired in 1993 and built a cabin in New Mexico, fifty miles from the nearest grocery store. He still stays in touch with many of the activists from back then. His old friends bring him great comfort.

***

The violence continued to escalate. Shortly after Zwerg and the other riders were beaten, King held a rally in Birmingham, and the church was surrounded by a baying mob. Federal marshals were wounded trying to hold the crowd back. King called Bobby Kennedy from inside the church, and Kennedy called the governor, demanding that he give protection. The governor replied that he could not guarantee King’s safety. Around two in the morning, with the marshals barely hanging on, the governor finally sent in the national guard to force the mob back. The following freedom ride from Montgomery to Jackson was accompanied by troopers, helicopters, and Alabama guardsmen on the bus.

On August 28, 1963, Martin Luther King Jr. spoke at the March on Washington to 200,000 who marched to the Lincoln Memorial. His “I have a Dream” speech would go down as one of the greatest speeches in American history. John F. Kennedy, listening from the White House, interpreted it as support for his Civil Rights bill. Eighteen days later, the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham was bombed. Fifteen were injured, and five children were killed. As the children were buried, the mourners sang “We Shall Overcome”—but many sang it with rage. Two months before, the same day that President Kennedy had given his strongest statement on civil rights, 37-year-old Mississippi civil rights leader Medgar Evers had been gunned down on his front steps, shot in the back with a high-powered rifle. The following year, during the Mississippi Summer of Freedom, three civil rights workers went missing, and were later found murdered. Their desire to be buried together was denied–segregation applied even to cemeteries.

Again and again, the violence of white segregationists forced the reluctant federal government to intervene, turning local issues into national crises. In essence, the civil rights activists sacrificed their bodies to take down a system of injustice—and they did so by refusing to hit back. In December of 1964, King was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his leadership, but by then many were beginning to get fed up with the relentlessness of it all. There was the televised brutalization of the marchers on the Edmund Pettus Bridge, where dead-eyed and gas-masked troopers with heaving clubs and snorting horses charged into a peaceful crowd, stunning Americans across the nation as shrieks were heard in the chaos veiled by the tear gas. King came to personally lead the next march, and James Reeb, who had answered the call to join the civil rights marchers, was murdered that same night. In 1966, James Meredith was shot and wounded on the second day of a march across Mississippi. King and the SNCC arrived to lead the march themselves—the last great march of the civil rights movement—but even, then, their meeting was tear-gassed and the activists badly beaten by the national guard.

Non-violence was contested as the Black Panthers and Malcom X arrived on the scene, but largely, it held. As King pointed out time and again, in the face of overwhelming and incontestable state violence, the only truly effective weapon was nonviolence. It was the one weapon for which the segregationists had no response. As King put it: ““To our most bitter opponents we say: ‘We shall match your capacity to inflict suffering by our capacity to endure suffering. We shall meet your physical force with soul force. Do to us what you will, and we shall continue to love you…But be ye assured that we will wear you down by our capacity to suffer.”

On April 4, 1968, Martin Luther King Jr. was gunned down by a lone assassin on the balcony of a hotel in Memphis, Tennessee. He had led a movement that successfully secured the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, had brought the segregationists to their knees, integrated the schools, and transformed public opinion on racial discrimination. All of this had been done by peaceful marchers singing hymns, turning the other cheek, and sacrificing their own freedom, comfort, and safety to secure rights guaranteed to them by the American Constitution. King and his colleagues had challenged America to become more Christian, not less—and forcibly confronted by the violence inherent to segregation and racial discrimination. The nation had responded.

***

No analysis of the civil rights movement—especially not an examination of the movement’s Christian character—can be complete without mentioning more recent controversies. For years, it has been well-known that King was unfaithful to his wife, and that the FBI used evidence of his adultery to blackmail him (at one point, infamously, sending him a letter urging him to kill himself before he was publicly exposed.) In fact, King’s close friend and mentor Rev. Ralph Abernathy revealed in his 1989 autobiography And the Walls Came Tumbling Down that King had sexual relations with two women on April 3, 1968 after his soaring “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” speech—the night before he was killed. Abernathy was attacked by other civil rights leaders for these revelations at the time, but they were later proven to be true.

On May 30, 2019, historian Dr. David Garrow—who won a Pulitzer Prize for his 1987 biography Bearing the Cross: Martin Luther King Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference—published further bombshell revelations after several other publications, including the New York Times, the Washington Post, and The Guardian, turned him down. The essay was titled “The troubling legacy of Martin Luther King,” and it revealed that King’s infidelities may, at one point, have included association with sexual assault. Garrow’s revelations were met with instant criticism from those who have long lionized King—an instinct I understand. A portrait of King once hung in my living room, and an original press photo of King still hangs in my library. I reached Garrow by phone shortly after the publication of his essay to ask him about his research.

“All of my new material comes from documents that the U.S. National Archives quietly put up on the web just over a year ago,” he told me. “It’s a huge amount of material dating from the 1960s and 1970s. There are more than 54,000 weblinks to documents on the Archives website—it’s almost impossible for anyone to sort through it and figure out what’s there. But I’ve been working with FBI documents for forty years, so I know the names of the people, I know the file numbers, the way the FBI’s filing system works. I was very much hoping this new set of material would have additional information about several of the most important paid black informants who targeted the civil rights movement. What’s new about Dr. King is on balance mainly from the FBI headquarters file on the FBI’s 1970s dealings with the Church Committee, one of the major congressional probes of the intelligence agencies, and it includes a lot of items detailing the FBI’s electronic surveillance of Dr. King during the 1960s.”

Included in the new material is FBI wiretap records. “The reliability rate of electronic intercepts, where they’re listening in, taking notes, turning on the tape recorder, is at the 99% or better level,” Garrow explained. While the recordings will remain under seal until 2027, the notes have been released, including a record of King and his friend Rev. Logan Kearse holding a party in the Willard Hotel in Washington, D.C. in 1964 with several female parishioners. The files claim that in the hotel room, the pastors “discussed which women among the parishioners would be suitable for natural and unnatural sex acts…when one of the women protested that she did not approve, the Baptist minister [Kearse] immediately and forcefully raped her” while King watched. Allegedly, King “looked on, laughed, and offered advice” during the assault. The FBI agents in the next room did nothing to intervene.

“That’s what’s in one of the documents of William Sullivan, the FBI’s assistant director for intelligence during the 1960s, the point person in the FBI’s pursuit of King,” Garrow told me. “Sullivan’s personal file on King was also the source of the suicide letter—no one has ever questioned the authenticity of that nasty letter that Sullivan typed out to send to King. This new material comes from exactly the same file as that suicide letter. Where the rape allegation is contained is in a draft revision that Sullivan’s working on to expand and enlarge a summary indictment of King’s behavior. I can tell from some of the latter pages of this document that he’s working on this revision expansion in the last days of March 1968. The timing is crucial to the story. In late March of 1968, Dr. King was organizing a massive protest, the Poor People’s Campaign, which was scheduled to descend on Washington, D.C. Throughout the federal government, the White House as well as the FBI, officials were exceptionally worried about what would transpire.” Sullivan abandoned the project when King was killed.

Logan Kearse of Baltimore, Maryland was a long-time friend of King’s who had also gone to theological school at Boston University. “I’ve long known Rev. Kearse’s name as someone who was present during this two-day, sexually-oriented party in early 1964, but this is the first time we’ve had an allegation of rape,” Garrow told me. “In my 1981 book on the FBI’s pursuit of Dr. King, I have a sentence there on page 116 that stemmed from three or four interviews with Justice Department attorneys who in the mid-1970s had themselves listened to the tape recordings and examined the transcripts. We have a 1977 public Justice Department report saying that attorneys listened to the tapes, read the transcripts, and that what’s on the transcripts is on the tapes. But those attorneys described to me their memories—this was about five years later—of force being used against a woman in a situation involving Dr. King. They conflated that Willard scene with another subsequent event where King and two friends had a bisexual orgy with a paid prostitute in Las Vegas, Nevada. The lawyers’ conflation led me to say that the allegation of force concerned Las Vegas, not the Willard Hotel in Washington. What I’m doing now is correcting the record, but the fact is that there was an allegation of force against a woman out there for 38 years in my book, and no one had every particularly focused on that before.”

The most important question, of course, is whether the allegations are true. Garrow believes that they are, and none of the responses to his Standpoint essay are very persuasive. “I think it is very, very likely that the characterization will prove to be primarily or largely accurate,” he stated. “I say that in large part because of my conversation many years ago with these Justice Department lawyers who had listened to the tapes, and there’s no question that those tape recordings contain Dr. King’s voice saying lots of nasty, obscene, unpleasant things. Now, I didn’t emphasize this additional factor in my Standpoint essay, but during these sorts of events Dr. King was, without exception, very drunk. It’s clear from the Las Vegas incident—the prostitute’s own account of the event—that King was heavily drunk. We’ve know for many years that by 1967-1968, King was a very heavy drinker, a problem drinker. I’ve know for years that King had multiple girlfriends, one very serious one in particular, Dorothy Cotton, who I publicly name for the first time in this piece because she passed away a year ago and the archives have put out all these documents with her name in them. All of us had previously respected her desire not to be named as his most important companion.”

How does one square the public King, with his soaring rhetoric, his moral crusades, his magnificent writing, and his professed Christianity, with the sordid, private King that is slowly coming into view? Garrow noted that when King was “preaching to his own congregation at Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, particularly in the last two years of his life, he is extremely confessional in describing himself as a sinner.” In one sermon just a month before he was shot, he used the analogy of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde to congregants who had known him his entire life. “In the last year or two I’ve read two book manuscripts—neither of these have been published yet—that have had a very powerful impact on me and my thinking about Dr. King,” Garrow said. “One of the authors, a psychiatry professor at Tusk University, has a very powerful analysis of how psychologically troubled Dr. King was in private because of how intense the burden of his public role was. I think where we’re headed in our understanding of Dr. King is a saddened appreciation of just how great a personal toll his public life took on him.”

***

We are now seeing the mantle of racial justice being taken up by leaders who are not the spiritual descendants of the Christian civil rights movement fueled by nonviolence that rose up in the 1950s and ‘60s. Now, organizations like Black Lives Matter see Christianity as part of the problem rather than an essential part of the solution, and bear far more resemblance to the Black Panthers and other violent revolutionaries than the movement led by the tortured but courageous Martin Luther King Jr. Many forget that while the civil rights movement was unfolding at the same time as the women’s liberation movement, the sexual revolution, and the beginning of the LGBT movement (the Stonewall riots kicked off in June of 1969), the premises of the civil rights movement were fundamentally different. King and his colleagues, for all their personal failings, advocated for an America that lived up to the ideals expressed in her founding documents—and in Scripture. Their speeches, their songs, and the rallying cries were infused with Scripture.

As King himself put it in his “Letter from a Birmingham Jail”:

There was a time when the church was very powerful–in the time when the early Christians rejoiced at being deemed worthy to suffer for what they believed. In those days the church was not merely a thermometer that recorded the ideas and principles of popular opinion; it was a thermostat that transformed the mores of society. Whenever the early Christians entered a town, the people in power became disturbed and immediately sought to convict the Christians for being “disturbers of the peace” and “outside agitators.”‘ But the Christians pressed on, in the conviction that they were “a colony of heaven,” called to obey God rather than man…By their effort and example they brought an end to such ancient evils as infanticide and gladiatorial contests. Things are different now. So often the contemporary church is a weak, ineffectual voice with an uncertain sound. So often it is an archdefender of the status quo. Far from being disturbed by the presence of the church, the power structure of the average community is consoled by the church’s silent–and often even vocal–sanction of things as they are.

Words that are as true today as when King wrote them fifty-seven years ago.

Hey Jonathon,

I hope you and your family are doing well. I couldn’t help but notice that you failed to mention part IV of your historical series, and so I thought I’d let you know just in case you missed it!

God Bless.

Thanks Krishna!