Blog Post

The Jewish girl who won Goebbels’ photo contest for “most beautiful Aryan baby”

By Jonathon Van Maren

In 1935, Nazi Ministry of Propaganda launched a photo contest. The purpose: To select “the most beautiful Aryan baby,” a particularly fine specimen of the Germanic race. The winning photo—and baby—would be featured as the Aryan poster child in Nazi propaganda to highlight the superiority of the Aryans and, conversely, the inferiority of the Jews and other races. Ten renowned photographers were asked to submit photos, with the winner being selected by Joseph Goebbels himself.

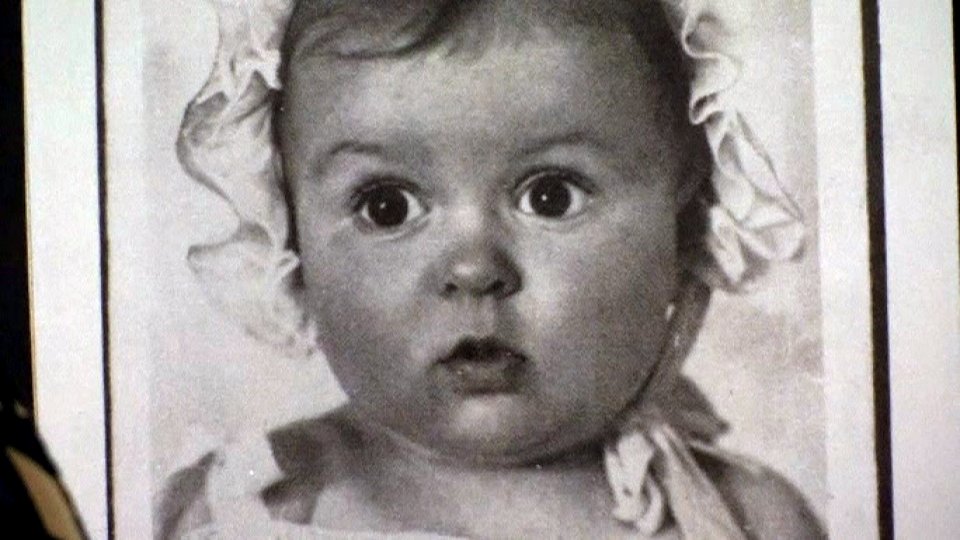

Out of a hundred pictures, Goebbels picked a photo of a gorgeous little girl with fat cheeks, dark eyes, and a frilly bonnet, and all agreed that it was an inspired choice. The beautiful baby’s face soon adorned Nazi magazines and postcards, drawing attention to the undeniable fact that Aryans were the master race.

There was only one problem. The little girl’s name was Hessy Levinsons, and she was Jewish.

Jacob and Pauline Levinsons were Ashkenazi Jews originally from Latvia, and both were opera singers who had studied at the Hochschule Music Berlin. Jacob had contracts to sing at 19 leading operas across the German capital, but when the Nazis took power, he lost all work. Jacob took work as a door-to-door salesman to make ends meet, and when Hessy was born on May 17, 1934, Pauline waited until she was six months old and then took her to the renowned Berlin photographer Hans Ballin for baby photos.

“Shortly thereafter, in 1935, my baby picture appeared on the front of a Nazi magazine—only Nazi magazines were allowed to publish at the time,” Hessy Levinsons Taft, now a professor of chemistry in New York, told me by phone. “It was a family magazine, and the headline over my picture said: ‘Sun in the House.’ My mother rushed back to the photographer to ask what had happened. He told her very quietly to close the door, pull the curtain, and took her to a backroom.”

After receiving the request from Goebbels’ ministry, Ballin told Pauline, he decided he “wanted to make the Nazis ridiculous”—and so had submitted a photo of Hessy to mock them. His joke had worked beyond his wildest imaginings—Joseph Goebbels had chosen a Jewish girl as “the perfect example of the Aryan race.” If the Nazis discovered their error, however, there would be hell to pay.

“My parents were terrified,” Taft told me. “This magazine appeared in every kiosk in Berlin, probably all over Germany. It was in the storefronts of stores that sold baby clothes with an announcement: ‘Buy beautiful clothes for your beautiful baby.’ It also got reproduced as a birthday card. It was sold all over the country, and beyond—my aunt, who lived in Lithuania, went into a store to buy me a birthday card for my first birthday and asked the woman: ‘Where did you get this?’ And she said: ‘I got this in Berlin and it’s not a doll, it’s a real baby. It’s a Berlin baby.”

Hessy’s aunt quietly bought the card and sent it to Jacob and Pauline inside an envelope. “The consequence of all this was that I could no longer be taken to play in the park,” Taft remembered. “My dear aunt Masha, who always took me to the zoo, which was apparently my favourite—that had to stop. I went outside wheeled in a carriage, always moving and never stopping for anyone to talk to me for fear of being recognized, particularly after I was one because I eventually learned to say my name: Hessy Levinsons. If anyone would have found out my real name, I wouldn’t be talking to you today.”

The Levinsons did have a very close call. Following the cancellation of his opera contracts, Jacob managed to set up a successful import and export business. “One day, he was arrested by the SS while his accountant was there. The accountant was a card-carrying Nazi, and when they arrested my father, he pulled a Hollywood-type trick—he got into a car and said follow that car! which ended up at the police station. The accountant barged through all the security and into the room where they were interrogating my father and yelled Heil Hitler! They let him in, listened to him, and the accountant said he would vouch for him. I think they trumped up some charge of tax evasion, which made no sense. But they released him.”

The Levinsons decided to get out of Germany with Hessy and her new little sister. The Latvian consul advised them to stay, citing the number of opera houses with potential work. The Levinsons were not convinced, and went first to Latvia to visit family, and then moved to Paris in 1938. In France, the story of Hessy’s baby photo came up when a Jewish doctor attending her for an illness commented on how cute she was, and Pauline told him what had happened in Berlin. The doctor wanted to publish the story in a Paris newspaper to ridicule the Nazi ideology, and although Pauline was willing, Jacob refused—there were simply too many Nazi sympathizers in France.

“In the summer of 1939, before France fell, my mother wanted very much to go back to Latvia for her mother to see my sister and me,” Taft recalled. “I always remember the big arguments that my parents had—it was a huge argument in Paris. My mother wanted to go back; my father said it’s dangerous, you may be stopped and asked questions and someone may even ask if you are Jewish. My father prevailed, thank God. Every one of my family members who was caught on the other side of Germany after September 1, 1939, was killed. I had one aunt, my mother’s oldest sister, who had left Latvia long before—when she married, she moved to Leningrad; her descendants are now living in Israel. Everyone else who was in Latvia was murdered.”

Soon enough, the Nazis arrived in Paris. It was tough in France, as the girls spoke German—a language that could not be used on the street. “It was very difficult for us. I was very unhappy at school. I had no friends, and I don’t know why but I think it must be related to the fact that I spoke German. But Paris was still Paris, so there were lots of wonderful things that could be done, in the beginning before the Germans started shutting Jews out of everything. Nazis did come to our apartment looking for us one day.” The family, fortunately, was out visiting friends—when they found out they were being hunted, they moved. Hessy, her mother and sister went to Bordeaux; her father stayed with a friend.

His friend courageously went back to the apartment and shipped some of their belongings to Portugal, where it was stored throughout the war and eventually made it to New York. The family managed to get smuggled into the “zone libre”–free zone–in southern France. Despite having obtained a US visa in 1941, they were unable to leave before the visa expired, but managed to get visas for Cuba in 1942. They settled there before immigrating to the United States in 1949.

The story of the little Jewish girl who was named the most beautiful Aryan baby by Joseph Goebbels remained a secret until 1987, when Taft was given the opportunity to write a chapter in a book about Jewish survivors from Latvia. The family agreed that it was time to share what had happened, and when the U.S. Holocaust Museum opened in Washington, Taft donated one copy of the original magazine as well as the only copy of the birthday card. The other copy of the magazine she donated to Yad Vashem.

“I am telling my story now after many years of silence as a way to expose the folly that existed and to make one small contribution towards erasing the prejudice,” she told me. “I feel a sense of satisfaction, a little sense of revenge, that I am alive and can tell the story.”