Historical Essays, Travel Journalism

Armenia’s memorial to the 20th century’s first genocide–against 1.5 million Christians

The Armenian Genocide Memorial rests atop the Tsitsernakaberd—literally, “swallow’s fortress”—a hill that rises sharply from alongside the Hrazdan River in Armenian capital of Yerevan. From the hilltop, on a clear day, you can see across the city to Mt. Ararat, where Noah’s Ark came to rest after the Great Flood. Yerevan is one of the world’s oldest continuously inhabited cities and Armenia is an ancient country, populated since at least 3,200 BC. The 44-metre memorial itself sits atop what was once an Iron Age fortress.

The Armenian Genocide Memorial complex includes a two-story museum built into the side of the hill and a garden of commemorative trees. An eternal flame sits at the center of twelve enormous grey concrete slabs, each of which represents one of the twelve lost Armenian provinces in Turkey. I arrived well before opening time before anyone arrived and descended the steps into the memorial. Fresh roses ringed the flame; by the end of the morning, Armenians with more flowers would line up to lay them by the fire.

A woman’s voice singing a haunting lament filled the memorial. I could see no speakers, and seemed as if it was rising from the earth. And he said, What hast thou done? the voice of thy brother’s blood crieth unto me from the ground. The flames twisted and flickered as her voice soared; concrete fingers cupped a bowl of eternal grief. Soviet regimes are not known for the magnificence of their architecture, but they knew how to build memorials. This one is called “The Temple of Eternity,” and it commemorates the 1.5 million victims of the Armenian Genocide, slaughtered by the Turkish regime from April 1915 to 1916 (and sporadically for years afterwards).

I have wanted to visit the Armenian Genocide Memorial and museum since I researched the subject during a 2019 trip to Turkey. My essay on the genocide, published in The European Conservative, attracted some unwanted attention after it was tweeted by the Armenian foreign minister and swarms of Turkish trolls descended to insist, with the arguments characteristic of denialists everywhere, that the number of the slain had been exaggerated; that the killings had not been a genocide; that I was lying and had obviously been paid by the Armenians for this propaganda (alas, I had not).

The Turks were not alone in suppressing the memory of the genocide. After Soviet Armenia was established in 1920, discussion of the genocide was forbidden. According to one display in the museum: “The discussing of national concerns was not tolerated by the Soviet regime, and both the commemoration of the Armenian Genocide and honoring its victims were under a gag rule. Even the study of this topic was under prohibition. Moreover, some citizens of Soviet Armenia because of their personal security even destroyed the relics that bore the memory of Western Armenia.” But in 1965, one hundred thousand people took to the streets of Yerevan for 24 hours, defiantly demonstrating to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the genocide and demanding that the Soviet authorities formally recognize it as such.

Photos at the time show a sea of people packing the streets; collective memory was surging to the surface of society, and it could not be ignored. The construction of the memorial began the following year, designed by architects Arthur Tarkhanyan, Sashur Kalashyan, and artist Hovhannes Khachatryan. It was completed in November 1967. The Armenian Genocide Museum-Institute, which has become a place of pilgrimage for visiting dignitaries, was opened in 1995 on the 80th anniversary of the genocide and features three major exhibit halls that methodically walks visitors through the events of the pogroms and genocide against the Armenian people.

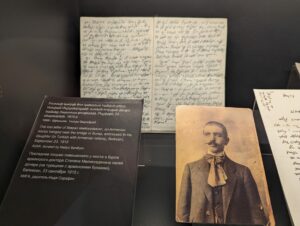

Like most modern museums, the Armenian Genocide Museum-Institute focuses more on conveying and commemorating the historic events than accumulating artifacts. But there are some. One glass case held the last letter of Stepan Meliksedekian, an Armenian doctor hanged near the bridge in Bursa on October 25, 1915. The letter is dated September 23, 1915, and addressed to his daughter. Another held a bullet shot by a Turkish soldier into a 25-year-old Armenian woman; she survived for 60 years with it buried under her breast but asked that it be removed after her death so that a Turkish bullet would not be buried on Armenian soil.

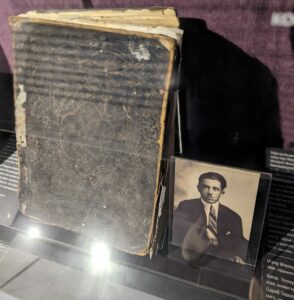

Perhaps the most moving artifact was a battered old family Bible. During and after the genocide, many Armenian children were kidnapped and forcibly “Islamized.” One 8-year-old orphan Serob Torrossian of Arabkir, forced to participate in the religion of his family’s killers, buried the family Bible in a secret place and for years went quietly to pray there, at the spot where it was hidden. Several displays recorded the fates of the kidnapped. Some were rescued after several years; a handful of family members were reunited; but even today, there are “Turks” of Armenian descent due to the apocalyptic violence of those brutal days.

The museum makes it clear that although ethnic and nationalist concerns played a role in the genocide, the Armenians were targeted and brutally murdered because they were Christians. One quote on display in three languages from survivor Arshaluys Mardiganian summed it up: “I saw my own mother’s body, its life ebbed out, flung onto the desert because she had taught me that Jesus Christ was my Saviour. I saw my father die in pain because he said to me, his little girl: ‘Trust in the Lord; His will be done.’ I saw thousands upon thousands of beloved daughters of gentle mothers die under the whip, or the knife, or from the torture of hunger and thirst, or carried away into slavery because they would not renounce the glorious crown of their Christianity…”

It is significant that the first genocide of the 20th century was perpetrated against Christians. In 2019, UK Foreign Secretary Jeremy Hunt warned that persecution against Christians worldwide was reaching “genocide levels,” especially in the Middle East, where ancient communities have been wiped out entirely and Christianity “is at risk of disappearing.” In Iraq, the number of Christians has fallen from 1.5 million before 2003 to less than 120,000 today; more than 336 Christians face some form of persecution for their faith worldwide.

As one display in the Armenian Genocide Museum stated: “Any unpunished crime is sure to reoccur.”

Outside the museum is a 100-meter wall with the names of towns and villages where massacres and deportations took place and plaques commemorating those who sought to help the victims. The institute is also a center for research into the Armenian genocide, and the gift shop contains many newly-published (or republished memoirs) from survivors. A decade ago, there were still at least 33 survivors left; now, I believe there are none. In a speech on August 22, 1939, just prior to the invasion of Poland, Adolf Hitler famously said: “Who, after all, speaks today of the annihilation of the Armenians?”

That quote now hangs in a museum dedicated to the memory of those annihilated Armenians, the survivors, and their many descendants, built into a hill topped by an enormous memorial overlooking the Ararat Valley. Hitler’s question is answered by 150,000 annual visitors: We do.

Thamk you.