Blog Post

How the Stasi infiltrated the East German church–but failed to stop the counter-revolution

By Jonathon Van Maren

At 1,207 feet high, the Fernsehturm broadcast tower soars above the skyline of what was once East Berlin. Berlin is one city now, but an invisible line still runs through it where the Wall once stood. On one side, many buildings are greyer, shabbier, and uglier—due both to the poverty of Communist architecture and the choking pollution that stained many of the landmarks. But the Fernsehturm, erected in 1969, was intended to be an architectural middle finger to the West, with a sphere modeled after the Soviet satellite Sputnik at the apex. This Babel, pointing towards the empty heavens, didn’t quite turn out that way.

Berliners soon noticed something. I saw it myself a decade ago, after the German guide I was with pointed it out, still chortling about it forty years later. When the sunlight strikes the panels of the tower, the light reflects into a nearly perfect cross, which could be seen right across the city. West Berliners promptly dubbed the shimmering symbol “the pope’s revenge,” and no amount of Communist engineering, short of tearing the tower down, could get rid of it. The government apparently even tried to paint over the reflective tiles, but to no avail. Like Christianity itself, it stubbornly remained.

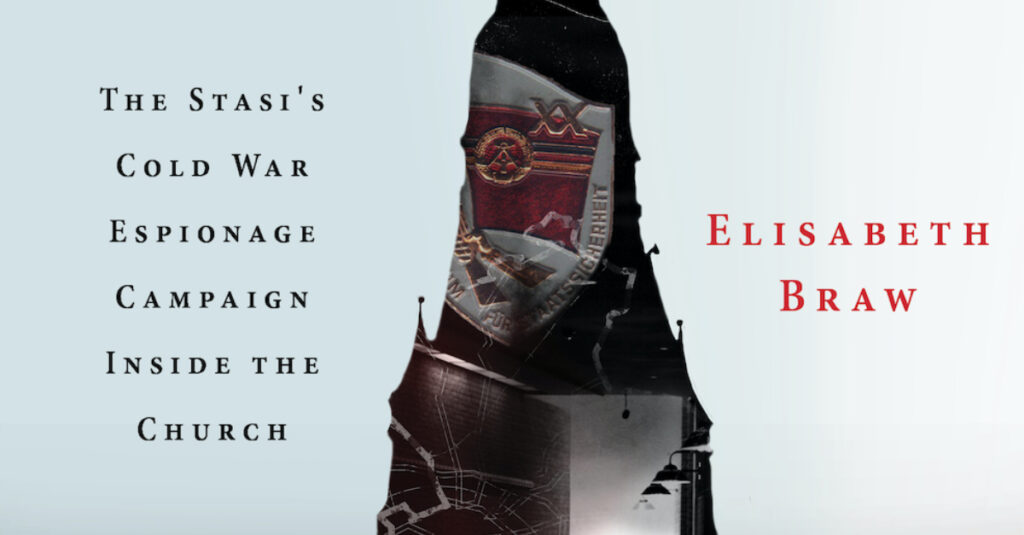

I thought of the Fernsehturm recently while reading Elisabeth Braw’s fascinating 2019 book God’s Spies: The Stasi’s Cold War Espionage Campaign inside the Church. Braw tackles the hitherto untold story of how one of the Warsaw Pact’s most effective intelligence agencies thoroughly infiltrated the East German church, amassed countless pages of material on nearly every single churchman—and still failed to prevent the protests that emanated from the churches and in a stunningly short amount of time facilitated the collapse of the GDR. It is a riveting spy story with compelling lessons for our current historical moment.

The Stasi’s very name still carries with it a whiff of danger, like a sudden rustle in a dark alley. Founded in 1950, the intelligence agency had 180,000 people on the payroll as informants at any given time; ratting on the neighbors was an East German way of life. The Stasi was everywhere—the churches, too. Department XX/4 was tasked with infiltrating the churches, and as Braw records in her book—based on interviews with former agents (like Colonel Joachim Wiegand), informants speaking for the first time, and information from Stasi files—it was phenomenally successful.

Unlike their counterparts in the KGB and other Warsaw Pact secret police forces, the Stasi generally did not utilize violence in their covert war against the churches. Instead, Stasi officers like Wiegand worked to domesticate pastors, theologians, and church workers utilizing a complex set of incentives: money; trips abroad; getting their children into better schools; promotions; even cigarettes or Western goods like lamps (the request of one bishop.) Another tactic involved catching clergy in compromising positions—financially or sexually—and subtly blackmailing them into cooperation. A handful, Braw found, even collaborated due to their loyalty to the GDR, which none had any reason to suspect would collapse so imminently.

Aleksander Radler, a theologian working in Sweden who actually helped Braw’s father with his doctoral defence, was working for the Stasi. Gerd Bambosky, an Easter German pastor, infiltrated Western organizations smuggling Bibles behind the Iron Curtain in minivans retrofitted with secret compartments. Bambowsky worked with Open Doors, Licht im Osten (Light in the East), and the British Bible Society, bringing in books and literature and turning it all over to his handlers—including, once, a letter from an elderly woman in Moscow thanking him for her Bible. The KGB destroyed a secret printing press in Latvia that Bambowsky located. Western charities, Braw notes, were “unknowingly filling Stasi and KGB storage rooms with religious literature.” The books were pulped; many intended recipients were arrested.

Often, Stasi recruits were just starting off in theological school, and would not become useful until years later, when their careers had advanced (often with a little help from their handlers.) This was the Stasi’s version of the Long March through the Institutions. Agents were rife in the World Council of Churches—the KGB even had Metropolitan Nikodim of Leningrad elected to a leadership role to ensure that the WCC didn’t condemn the brutal Soviet crackdown of the Prague Spring. In a move reminiscent of current religious debates, the WCC instead focused on “the eradication of racism—an issue where it was easy to single out the United States for criticism.”

Braw found Joachim Wiegand, who led the Church Bureau, to be an ironically honorable man—despite her attempts, he refused to unmask any of the many East German pastors who worked for the Stasi but were never found out. Fortunately for many of those who betrayed their flocks and reported on their brethren, the Stasi in the Church Bureau sensed that the GDR was teetering as massive peace prayer services began to ignite marches. In 1989, as East Germans flowed across the border, many officers began to shred their files. The GDR was dying, and her spies knew official lies when they saw them—they were, after all, usually responsible for ensuring that people believed them. After a massive 70,000-strong march in Leipzig, Wiegand began to shred files, too. Scores of wolves in shepherds’ clothing still hold their posts today.

But God’s Spies is more than a gripping tale of ecclesiastical espionage. There is much for today’s Christians to learn from the story of the East German church. As Braw notes in her conclusion, reunification and the end of Communism ironically accomplished what the Stasi never could: The near-total death of Christianity in Germany, where 92% of people abstain from church services (although much higher numbers claim some denominational affiliation.) It is staggering to consider that the very churches who midwifed the counter-revolution that toppled the Berlin Wall were promptly abandoned in the years that followed.

There were, says Braw, many reasons for this. First of all, when the goods and services of Western capitalism came rushing in, people suddenly became too busy for church. “Isn’t that the tune of secularization everywhere?” she remarked. With everything at their disposal—or at least, seemingly within reach—people had time for everything but God.

“The biggest threat to Christian communities isn’t dictatorships, authoritarian regimes, or violence,” Braw told me. “We have seen through the centuries that Christians are incredibly brave and just keep going. The biggest threat is really distraction through materialism. You don’t realize what a distraction or a temptation it is. That’s what’s happening not only in former East Germany, but in a lot of other countries, as well. You get so distracted by all these things you can buy and things you can do with your money, and that becomes more powerful as an alternative to Christian faith than the brutal regimes people used to live in.”

In fact, the churches in East Germany actually grew under Communist rule because it was one of the only semi-free intellectual spaces where people could gather. People saw church as a refuge, and they gathered there. In part, this fueled a cultural Christianity that was centred not in Christ, but in opposition to the regime—many pastors ordained in these years, says Braw, would likely not have become pastors if they had not lived in a Communist country. Once people no longer needed a refuge from oppression, they left. Their roots, in other words, were not deep enough or spiritual enough.

“In a way, the East German churches had an advantage, because it was clear to the rest of the population that they were something different,” Braw told me. “Churches in the Western world today could learn from that. If it isn’t clear that they represent something different, why would people come to them? That is the tale of two generations for the East German churches—during the worst period of harassment, the church had a unique role in that society.” Now, mainline churches across the West are collapsing because they have attempted to remain relevant by selling their souls and abandoning their jewels of truth.

Individual pastors were bought off under Communism with money and often paltry material rewards—a generation following was bought off and lured away with everything Western capitalism had to offer. For millions, digital porn, entertainment, cultural accommodation, and materialism has done what persecution has never been able to accomplish. The godless Communist state was replaced by the Western pantheon of prosperity. (“And the people bowed and prayed/ To the neon god they made.”) The honeymoon lasted decades—until many people, even many atheists, began to wonder: Is this all?

It was Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s 1978 commencement address at Harvard, says Braw, that summed it up.

“Every citizen has been granted the desired freedom and material goods in such quantity and of such quality as to guarantee in theory the achievement of happiness — in the morally inferior sense of the word which has come into being during those same decades,” the Russian sage told his audience. “In the process, however, one psychological detail has been overlooked: the constant desire to have still more things and a still better life and the struggle to attain them imprint many Western faces with worry and even depression, though it is customary to conceal such feelings. Active and tense competition fills all human thoughts without opening a way to free spiritual development.”

It is sobering to consider that consumerism and wealth killed Christianity where Communism and the one of the world’s most feared intelligence agencies could not. It begs an important question, Braw reflects: “What would be our price?”