Blog Post

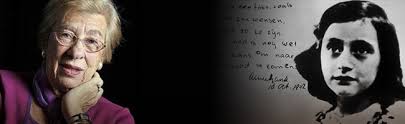

Becoming Anne Frank’s step-sister

First published in the Times of Israel on November 13, 2013 (Link: http://blogs.timesofisrael.com/becoming-anne-franks-step-sister/).

I first visited the Anne Frank House in 2004. From the outside, it looks just like any of the other tall, narrow Dutch houses of Amsterdam. Inside, behind a bookshelf, is the remnants of a tiny world once inhabited by eight hidden Jews, all descended from the Chosen People, chosen by Hitler to suffer all the hellish furies spawned in the minds of the Aryan demons who perpetrated them. Here and there, things that survived the carnage remain behind, flotsam and jetsam of lives now gone. One of them, sitting behind glass, is the diary of Anne Frank. I joined the other tourists peering at the neat, cursive handwriting of the little girl whose imagination had captured the attention of the generations who followed.

To 84-year old Eva Schloss, Anne Frank was just another girl in her circle of friends in war-time Amsterdam. She and her family—father, mother, and brother—fled Austria in the wake of Anschluss, heading for perceived safety in the Netherlands. There, as a young girl, she met the Frank family—Otto, Edith, Margot, and Anne.

“If I were to give a lot of detail” about Anne, she told me from London, England, “I would be making it up. She was just one of my playmates. She was very lively, and very nice, but I was a tomboy, and she was really a sophisticated girl. So, you know, we were not best friends. She was interested in hairstyles, clothes, and boys, and I had a brother so boys were no mystery to me. We used to play as kids do, skipping and gossiping.” Anne Frank was just another little girl, part of a group of about thirty children, Eva thinks, many of them expatriates from Germany and Austria.

Anne Frank, however, wo uld become Eva’s step-sister years later, on the other side of the inferno that the world would come to call the Holocaust.

uld become Eva’s step-sister years later, on the other side of the inferno that the world would come to call the Holocaust.

In July of 1942, Eva’s brother got called up for deportation. Rather than send him off to what was already rumored to be certain death, the family decided instead to go into hiding.

“I was with my mother,” she told me, “we couldn’t find a place that would take four people. The boredom was for me nearly unbearable. As I said to you, I was a very outdoor, lively child, and suddenly I had to sit still day in, day out, day in, day out. So that was terrible. As well, the Nazis did house searches. They came into houses, knocked on doors, and searched the houses, so we had a hiding place within the hiding place. When they came at night, we had to quickly go into those hiding places, hoping they wouldn’t find us.”

They were always uneasy, and unlike the Frank family, always on the move. “We were in seven different places,” Eva remembers, “They were people who hated the Germans. One was a single lady who was a teacher, once it was a family with two young boys, but all anti-German, anti-Nazi. Very patriotic Dutch, usually good Christian people who thought they had to help other people.”

Not all remained patriotic—some were eager to dip their hands in the blood of their neighbors. In 1944, on her 15th birthday, Eva and her mother were betrayed by a Dutch nurse working for the Gestapo. Her father Erich and brother Heinz were caught by the same network, and the family saw each other again on a train heading for the death camp Auschwitz.

“We all knew,” Eva remembers, “What was going on in Germany and Poland.”

Her memories are traumatic and her descriptions truncated. “Fear. Fear of being killed, which we nearly were. Terrible, terrible deprivation. Starving. Illness. Hard labor. Lice. Terrible. Terrible selections.”

She survived, in part, by remembering. “I remembered the wonderful life we had in Austria,” she told me. “I wanted a boyfriend. I wanted to get married. I wanted children. I never, ever gave up hope that a miracle would happen and we would make it. My mother and I were lucky. We made it. My father and brother didn’t survive.” Erich and Heinz died on one of the infamous death marches, taken from the camp and marched to death as the Russians approached.

Eva and her mother were rescued, although the liberation, having come at such a cost, is an event that Eva remembers as “joyless.” The miracle she had hoped for had taken place, but her family had been destroyed. So had much of Europe—as she and her mother travelled through Poland, Ukraine, and Russia, she witnessed the “terrible, terrible devastation” of the Nazi Scorched Earth Policy. As the war ended, the rebuilding began.

Eva moved to London and met another refugee, Zvi Schloss, whom she married in 1952.

Eva’s mother Elfriede had also met other Jewish refugees. One such refugee was Otto Frank. He had lost his wife and both of his daughters in the Nazi death camps. They grew close, and in 1953, they married. Eva’s mother joined Otto Frank on the road, promoting the diary of Anne Frank.

“It was a wonderful marriage,” Eva remembers, “They really worked together, and my mother was really very happy I must say. Otto and my mother really loved each other.”

While her mother and Otto Frank made Anne’s story one of the most well-known stories in the world, Eva didn’t tell her story until the 1980s, at an exhibition featuring the girl she had met so many years ago. She was asked to say a few words, and she told her story for the first time. “It changed my life,” she said.

And now it changes the lives of others through her books, Eva’s Story and The Promise, and through the story she tells to audiences around the world. We hear her story and read her books as tourists from another era, trying to understand what happened, squinting into the past like we squint at Anne Frank’s battered diary, lying behind glass in the building that became her final home. Eva helps people try to make sense of it all, and warn us that we must work harder, try harder, to ensure that such things become history and not current events.

For as her stepsister Anne wrote, “If we bear all this suffering and if there are still Jews left when it is over, then Jews, instead of being doomed, will be held up as an example.”

And Eva’s story is one to heed.