By Jonathon Van Maren

The release of Rod Dreher’s The Benedict Option: A Strategy for Christians in a Post-Christian Nation last month marks the arrival of a book hotly debated in Christian circles since long before its publication. Rod Dreher, the author of wonderful books such as The Little Way of Ruthie Leming: A Southern Girl, a Small Town, and the Secret of a Good Life and How Dante Can Save Your Life, is a traditionalist blogger over at The American Conservative. For years he has been advocating for Christians to embark on a strategic withdrawal from the broader culture in order to nurture Christian sub-cultures rooted in tradition, a knowledge of the past two thousand years of Christian history, and the pursuit of personal holiness. And for years, Dreher’s Benedict Option has been discussed in Christian circles, with some insisting his strategy is tantamount to surrender, while others gravitate towards the concept as a roadmap to weathering the secular storms ahead.

I found The Benedict Option, named after the fourth century monk St. Benedict and the religious communities he founded after the fall of the Roman Empire, to be a compelling and sobering read. Dreher does not only analyze the current state of the culture—something I examined in detail in my own book released last year—he also examines the state of the church. While statistics would seem to indicate that American Christians are still in the majority, this is only true if one does not examine what it is that these Christians actually believe. Most, Dreher says, do not believe in the Christianity encapsulated in the ancient creeds, but rather subscribe to something he calls Moralistic Therapeutic Deism. In other words, Christianity is about living a “decent life” rather than a genuinely Christian one as articulated by Scripture, and God exists to serve people rather than the other way around. Instead of holding to Christian principles, many of them are driven by three things: individualism, hedonism, and materialism. As Dreher puts it:

Too many churches function as secular entertainment centres with religious morals slapped on top, when they should be functioning as the living, breathing Body of Christ. Too many churches have succumbed to modernity, rejecting the wisdom of ages past, treating worship as a consumer activity, and allowing parishioners to function as unaccountable, atomized members. The sad truth is, when the world sees us, it often fails to see anything different from nonbelievers. Christians often talk about “reaching the culture” without realizing that, having no distinct culture of their own, they have been co-opted by the secular culture they wish to evangelize.

As hard as that is to read, Dreher is correct. In 2014, Christianity Today reported on an exploding trend they dubbed “sexual atheism” as on the rise among single Christians, citing a study that showed 63% of single Christians indicated that they were willing to have sex before marriage and estimating that nearly 9 out of 10 single Christians were “sexual atheists.” A recent study by the Barna Group found that only 18% of Millenials find Christianity relevant to their lives. And even looking beyond the statistics—who among us does not know Christians who have been carried along with the secular flow on issues ranging from gay marriage to transgenderism? Who was not shocked by dozens of Christians friends on Facebook posting rainbow profile pictures to celebrate the legalization of gay marriage?

As Dreher points out, Christian denominations that have abandoned modes of worship rooted in centuries of tradition for knock-off versions of secular culture have done much to contribute to this. An example springs to mind. In 1964, the late conservative titan Phyllis Schlafly wrote a best-selling book titled A Choice, Not an Echo, condemning the mainstream Republican Party for being a cheap imitation of the liberal Democrats rather than a truly conservative alternative. Similarly, today Christian denominations are realizing and must realize that what people want is a choice, not an echo—an alternative to the vacuous secular culture that surround them, not a “Christianized” imitation of it. This, too, is borne out by statistics—across North America, liberal churches are being abandoned. The United Church of Canada, which championed the legalization of abortion and gay marriage, is selling off thousands of its properties as parishioners drift away. A recent study by Dr. David Millard Haskell of Wilfrid Laurier University revealed that liberal churches are shrinking, and conservative ones are growing. In a society that has forcibly removed Christianity from its position of cultural prestige and treats many of its tenets as hateful, there is immense cultural pressure to abandon it entirely—and those who choose to remain faithful often have no time for a weak and watered-down facsimile.

Dreher delivers a truth that is tough to swallow, but true in many ways. Thousands of young Christians have never been exposed to the Psalms, hymns, and spiritual songs mentioned in Ephesians 5:19, but instead rock ‘n roll vandalizations of hymns like Amazing Grace and tuneless “worship songs” utterly disconnected from the Christian musical traditions of the previous two thousand years. Church youth groups, he writes, are often more focused on entertainment than theological instruction (reminding me of a scathing satire article describing a man who decided to turn his paint-balling hobby into a “ministry.”) In a recent interview, Dreher told me that faculty at Catholic and evangelical colleges give a dismal assessment of the biblical and theological knowledge of most of their students. In other words, many, if not most of today’s Christians are completely unaware of what Dreher calls “the Christian story,” something that conservative titan Ted Byfield has been attempting to raise awareness about for decades in Canada. (Byfield founded the Society to Explore and Record Christian History for precisely this reason, producing a beautiful and indispensable 12-volume history “The Christians,” which I cannot recommend highly enough.)

This sobering analysis of North American Christianity lays the groundwork for Dreher’s thesis that the Benedict Option is necessary. Any Christians who thought there was strength in numbers are faced with the reality that this is an illusion. The storms of secularism are just beginning to beat down upon a house largely built on the sand, and we are already beginning to witness the walls crumbling as young people abandon Christianity in droves and high profile political figures who claimed the Christian mantle for convenience defect to the ranks of secularism. The North American churches are porous and taking on water fast—just when a robust counterculture is needed to withstand the floods.

And the floods are coming. Rod Dreher traces the roots of the rot even further back than the Enlightenment, and then gives readers a lighting fast tour through to the Sexual Revolution, the tipping point of our society’s descent into insanity. Legal abortion, the severing of sex from procreation, hook-up culture, pornography, no-fault divorce and the disintegration of the family, gay marriage, and now transgenderism—the outright rejection of biological reality itself. Transgenderism, Dreher writes, is actually trendy now—kids are coming home from school and announcing that they are actually the opposite sex, and then demanding that their parents get them hormone treatments. Parents are often too afraid to say no, which isn’t surprising. (In Canada, Ontario’s Bill 89 could have children forcibly removed from their parents’ homes if the parents refuse to go along with this delusion.)

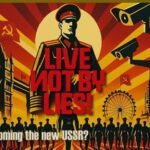

In fact, so many people are terrified that speaking the truth about what is going on will cost them their jobs that most of those Dreher interviewed for the book asked to be kept anonymous, as if they were voluntarily putting themselves in a witness protection program in order to avoid getting “whacked” by what even Bill Maher called “the gay mafia.” For example, an LGBT group called Campus Pride has put over one hundred colleges on a “shame” list and are attempting to persuade businesses to hire none of them. Dreher gives examples of people in the business world who are under massive pressure to out themselves as “allies of the LGBT community,” which comes with a badge to wear. This, of course, makes it very obvious if you decline to wear one. (It reminded me of the red scarf of the Young Pioneers in the Soviet Union, the Communist version of boy scouts—Christian children were not permitted to be members, and thus everyone could easily identify those who were different. If you were a Christian student, you lacked a red scarf—and painted a target on your back.) And of course, mandatory diversity and inclusion training are rapidly becoming the norm.

Christians are under fire in nearly every profession. Law societies in Canada—and Dreher mentions this—are refusing to accept law students from a Christian school based on the voluntary lifestyle contract those students choose to submit to when attending Trinity Western University. Most secularists reject the idea of conscience rights in the medical field out of hand, with abortion rights activists and suicide activists insisting that doctors have a “duty” to provide whatever “care” is asked of them—even if that involves skull-crushing and lethal injections rather than actual healthcare. At a minimum, they insist, Christian medical professionals should be forced to refer people to those who would carry out these deeds. This should not be surprising: a medical establishment that has accepted the tasks of dismembering babies and dispatching the elderly will hardly flinch when it comes time to destroy your conscience. Christians everywhere are being pushed to the fringes. As I wrote elsewhere, it is the same tactic used in the Eastern Bloc under the USSR: Even where persecution was not overt, Christians were given a choice: You can be a Christian, or you can be successful.

And so what is to be done? Dreher makes no apology to those who might scoff at him for being alarmist. “When the world is deaf,” he told me during our interview, quoting Flannery O’Connor, “you have to shout.” Anyone who is paying attention to the state of the church and the state of the culture knows that Dreher’s prediction of a new Dark Age is at least a possibility, and certainly one that should be prepared for. Mary Eberstadt began her own 2016 book It’s Dangerous to Believe recounting evenings she spent with groups of Christians across North America, all having the same conversation: What will we do? Where will we go? I have been part of similar conversations. The Benedict Option is being discussed far and wide, even as talk of the “self-sustaining communities in the wilderness” Christians joke about edge from the arena of gallows humor into cautious speculation.

Dreher addresses politics first, and he makes many compelling observations. The Republican Party is losing interest in defending Christians and standing up for social conservative values, especially as Big Business wraps itself in the rainbow flag and the longstanding Republican alliance between social conservatives and the corporations abruptly collapses. The consensus Republicans are trying to protect is now far from Christian—it brings to mind Ambrose Bierce’s wry definition of a conservative: “A statesman who is enamored of existing evils, as distinguished from the Liberal who wishes to replace them with others.” While we must remain engaged in politics to some degree, Dreher says, we cannot count on political conservatism in a culture with everything left to fight for and nothing left to conserve.

Here is where I’m not sure I agree with Dreher. In his analysis, the Religious Right failed miserably by relying on politics as the answer to cultural problems. Repeatedly, he excoriates the previous generation of Christian leaders for their miscalculation and lack of faithfulness. But I’m genuinely curious as to who Dreher is referring to. Is it Dr. James Dobson, who started Focus on the Family, and has spent his life trying to assist healthy families and healthy communities in flourishing? Is it Dr. Jerry Falwell, who for all his public bombast still counted as his greatest achievement the founding of Liberty University, the home of brilliant scholars such as Dr. Judith Reisman and Dr. Karen Swallow Prior, and trains thousands of young Christians every year? Is it Francis Schaeffer, a scholar obsessed with reintroducing the rich history and art of Western Civilization to evangelical Christians? The Religious Right made many mistakes, and hindsight is 20-20. But I’d genuinely like to know which of the prominent Christian leaders of the past decades believed or acted as if politics were the answer to spiritual and cultural problems.

Dreher admits that politics is necessary for the sustenance of the Benedict Option, citing especially the fight for religious liberty, as well as active engagement in local politics. But again, I could not help but wonder: If the secular onslaught against Christian communities is as fierce as Dreher says it is—and I think he’s right—then how is a strategic withdrawal going to be helpful? Dreher emphasizes prudence in picking our battles, and again he’s right. But which ones? How far do we let them advance? When we are being attacked on so many fronts simultaneously, it’s hard to see where we have the space for withdrawal. When the orcs are over the walls and throwing ladders up against the keep, we don’t really have time to discuss which wall to abandon. Every incursion on religious liberty now poses a threat, and every bad legal case threatens to set a new precedent for all Christians. Local politics are essential, but the Leviathan crushes the local.

To preserve religious liberty, Dreher writes, Christians are going to have to work together across denominational lines and recognize what Francis Schaeffer called our “co-belligerence.” Dreher is writing for what he calls “mere Christians,” those who still hold to basic orthodoxy—traditional Catholics, Eastern Orthodox, and conservative evangelicals. It is time for mere Christians to form what Charles Colson and Richard John Neuhaus called an “ecumenism of the trenches.” Those of us in the pro-life movement are already familiar with such alliances—our camaraderie extends to all those who fight for the lives of the pre-born, and everyone pulls together for the same cause. I smiled reading Dreher’s descriptions of his own Eastern Orthodox tradition, because it brought back memories of sleeping in the spire of a Ukrainian Catholic cathedral while crossing the country on a pro-life tour, with incense still drifting up through the wooden floorboards. The priest had heard that pro-lifers were coming through his town and needed a place to stay, and had found a way to accommodate us at once.

And as always, education is key. Dreher is blunt: Pull your children out of public schools. The transgender trend is spreading, and it is impossible for parents to counter forty hours of secular—and in many cases anti-Christian—education with a few hours of church, catechism, or discussion at home. Sending children off to a public school in hopes that they will be a “Christian witness” is rather like the Children’s Crusade, and will probably end in a similar fashion. Christian schools, classical education, homeschooling, or combinations of these options should be seriously considered and pursued by all Christians. As one pastor once put it, we cannot send our children off to be educated by Rome and then be surprised when they come back Romans. It is essential, Dreher writes, that our children learn the Christian transcendentals of goodness, truth, and beauty—things our culture has difficulty defining, much less teaching.

At the end of the day, Christians have much to prepare for. We need to ready ourselves to make difficult career choices, Dreher points out. The professions we once hoped to join may be closed to us, and it may be wiser for us to decide on a job that will not force us into impossible conundrums of conscience. Many young Christians are already making such decisions. We need to build communities of like-minded Christians to raise and educate our children, nurture faith, and tell the Christian story. We must prepare for a Dark Age, so that if it comes, our communities can be a light in the darkness.

To be continued with Part II: The Benedict Option I Grew Up In

_______________________________________

For anyone interested, my book on The Culture War, which analyzes the journey our culture has taken from the way it was to the way it is and examines the Sexual Revolution, hook-up culture, the rise of the porn plague, abortion, commodity culture, euthanasia, and the gay rights movement, is available for sale here.

I don’t believe there is an answer to this secular onslaught outside of a conversion to Catholicism. Anything less is a liberal lie. Dr Dobson has done great work with the family however his support of contraception (which is a root cause of much disorder) illustrates my point. I’ve seen it in pro-life work. To work with Protestants, Catholics agree to be silent on contraception. The Social Reign of Christ the King and nothing less is the answer.

I’m a Protestant (Dutch Reformed), and I was brought up to oppose contraception. All Christian denominations agreed on this prior to the Lambeth Conference in 1930.

“I don’t believe there is an answer to this secular onslaught outside of a conversion to Catholicism.”

This makes no sense. (a) Roman Catholicism as you know it didn’t exist until the Augustinian era. Before that, while it’s true that churches were by and large on the same page doctrinally, those doctrines certainly didn’t include specifically RC dogma, and those churches weren’t under centralized governance.

(b) Contrary to popular belief, Roman Catholicism is not a monolith. Individual Roman Catholics regularly ignore various RC teachings, live in immorality, and attempt syncretism with antichristian worldviews. As individuals, RCers are no more united than Protestants as individuals.

(c) Birth-control is neither here nor there, since while the Bible teaches us to value children and family, it doesn’t specify that children “must” be the product of marriage (relatedly, Scripture teaches overtly that one isn’t obligated to seek marriage; why assume, then, that all marrieds “must” seek children? – what matters are the reasons behind that decision; are they selfish or Godward?). Sexual fidelity in marriage, on the other hand, is certainly part of the biblical worldview, because it symbolizes the union between Christ and the Church (I use capital-C “Church” to refer to the worldwide body of Christ).

(d) Just live according to God’s word. Period.