Blog Post

Vietnam: The War that transformed America

By Jonathon Van Maren

My introduction to this series on the 20th century, “The Century that Changed Everything,” can be found here. Part I is “The World Before the War”. Part II, “How the Great War transformed Western civilization–and is still with us today,” can be found here. Part III, “The Second World War: Saving Christian civilization from Hitler’s Reich,” can be found here. Part V, “The Shoah: The murdered multitudes and the righteous few,” can be found here. Part VI, “An eyewitness to the birth of Israel and the Convoy of 35 speaks,” can be found here. Part VII, “America versus the Evil Empire, can be found here. This is the eighth installment in this series.

The United States of America was involved in countless conflicts throughout the 20th century, but none has lingered in the national psyche as painfully as the Vietnam War—arguably, the only war the global superpower ever lost. Much of what is going on now is explained by what happened then, and the Vietnam War’s far-reaching effects are complex and pervasive. According to Lynn Novick, who partnered with filmmaker Ken Burns to produce the gargantuan 17-hour masterpiece The Vietnam War for PBS, “so much of the disunion and cynicism we see today dates back to the Vietnam era.” In fact, even “the tension between the secular and religious is part of it, but also class tension and ethnic tension, and the whole urban/rural and red state/blue state split. This didn’t come out of nowhere. A lot of that started to bubble up during Vietnam.”

So how did an obscure territory in Indochina become America’s Achilles heel? As the 20th century dawned, nationalist sentiments were beginning to stir in the French colony, and the most prominent figure to emerge was Ho Chi Minh, the Communist founder of the Viet Minh. Ho Chi Minh’s forces briefly seized control of Hanoi and declared independence following the end of World War II, but French troops soon arrived and forced the Communists into the north of Vietnam. Ho called on the U.S. for support, but Cold War tensions caused the Americans to instead throw their support behind the French. Despite that, Viet Minh troops under General Vo Nguyen Giap overran the French base at Dien Bien Phu on May 7, 1954. France sought a peace settlement, and the Geneva Accords divided Vietnam into North and South Vietnam, with the Communists taking control of the North. Vietnam was to be reunited during elections in 1956.

Fatefully, the United States feared the possibility of Ho Chi Minh taking power in Vietnam. According to the Domino Theory, a Communist takeover could trigger similar takeovers across Southeast Asia. To counter this, the U.S. began supporting President Ngo Dinh Diem, a corrupt and incompetent leader who persecuted South Vietnam’s Buddhist majority. Diem’s unpopularity fueled Communist resistance, and the primary opposition to Diem became known as the National Liberation Front, or Viet Cong. At this point, John F. Kennedy began sending troops to Vietnam under the pseudonym of “military advisors” to train the ARVN (South Vietnamese army), but quickly realized that Diem was a lost cause. On November 2, 1963, Diem was assassinated by his own generals in an American-backed coup. Twenty days later, JFK was shot in Dallas, and the war was bequeathed to Lyndon B. Johnson—with 16,000 military personnel already in Vietnam, and 200 fatalities and counting.

Johnson had hoped for a presidency defined by domestic policy and his “War on Poverty.” It was not to be. In 1964, a North Vietnamese torpedo boat allegedly attacked the U.S. Navy in the Gulf of Tonkin, and the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution authorized Johnson to “take all necessary measures to repel any armed attack against the forces of the United States.” Troops began to head to Vietnam, and massive bombing campaigns began (including 1965’s “Operation Rolling Thunder.”) By the end of 1966, almost 400,000 U.S. troops were in Vietnam, bogged down in a bloody war of attrition where success was measured entirely by the number of Viet Cong casualties. The U.S. hoped to overwhelm the Communists by sheer bloodshed, but jungle warfare and guerilla tactics caused widespread demoralization and mounting frustration amongst the troops. Bombings increased, and the U.S. employed both napalm and Agent Orange, a defoliant herbicide. By March of that year, over 2,700 Americans had been killed.

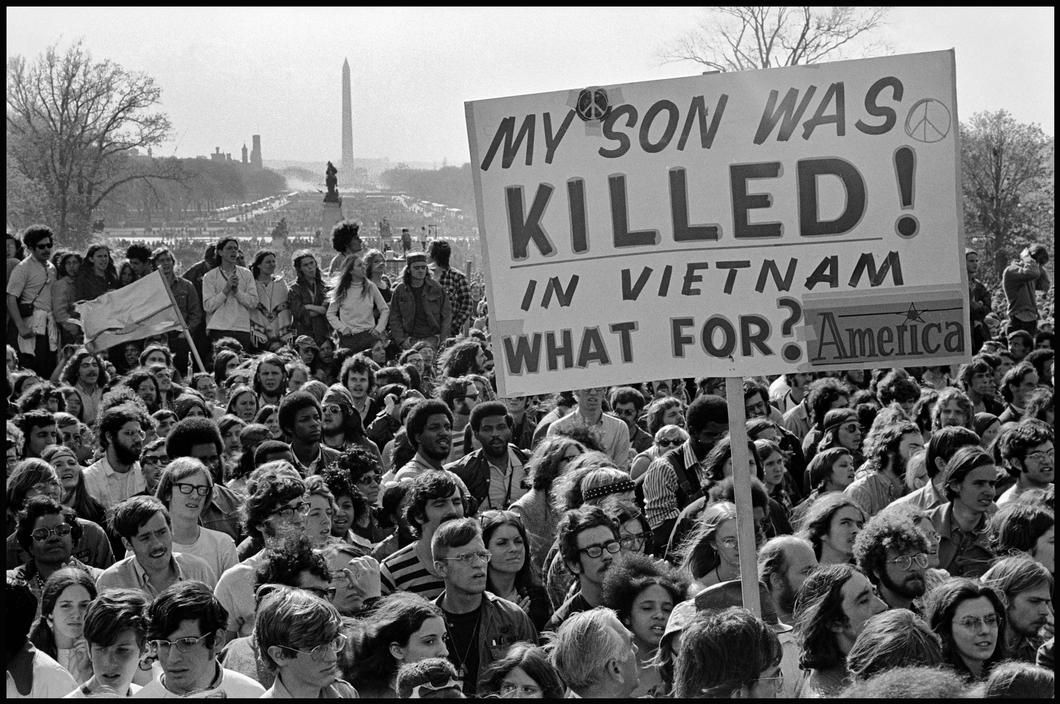

In 1968, the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Army launched an all-out attack to turn the tide. The Tet Offensive struck almost thirty American targets and dozens of other cities across South Vietnam simultaneously. The U.S. pushed them back, but media coverage cast the victory as a defeat. American morale continued to drop, occasionally culminating in cruelty and tragedy, the My Lai Massacre that year being the most infamous example . Back in the U.S., the anti-war movement picked up steam, as brutal footage and photographs from Vietnam began to turn public opinion against the war. National guardsman and cops clashed with protestors, police brutality exploded outside the 1968 Democratic National Convention, and Lyndon B. Johnson decided to step out of presidential politics rather than run for a second term. As the country tore itself apart, Richard Nixon inherited the war from Johnson, and the Pentagon Papers, published by the New York Times and the Washington Post, stunned the public with revelations that top American officials had believed that the Vietnam War was unwinnable for years—but had continued to send boys to die overseas in order to avoid admitting defeat.

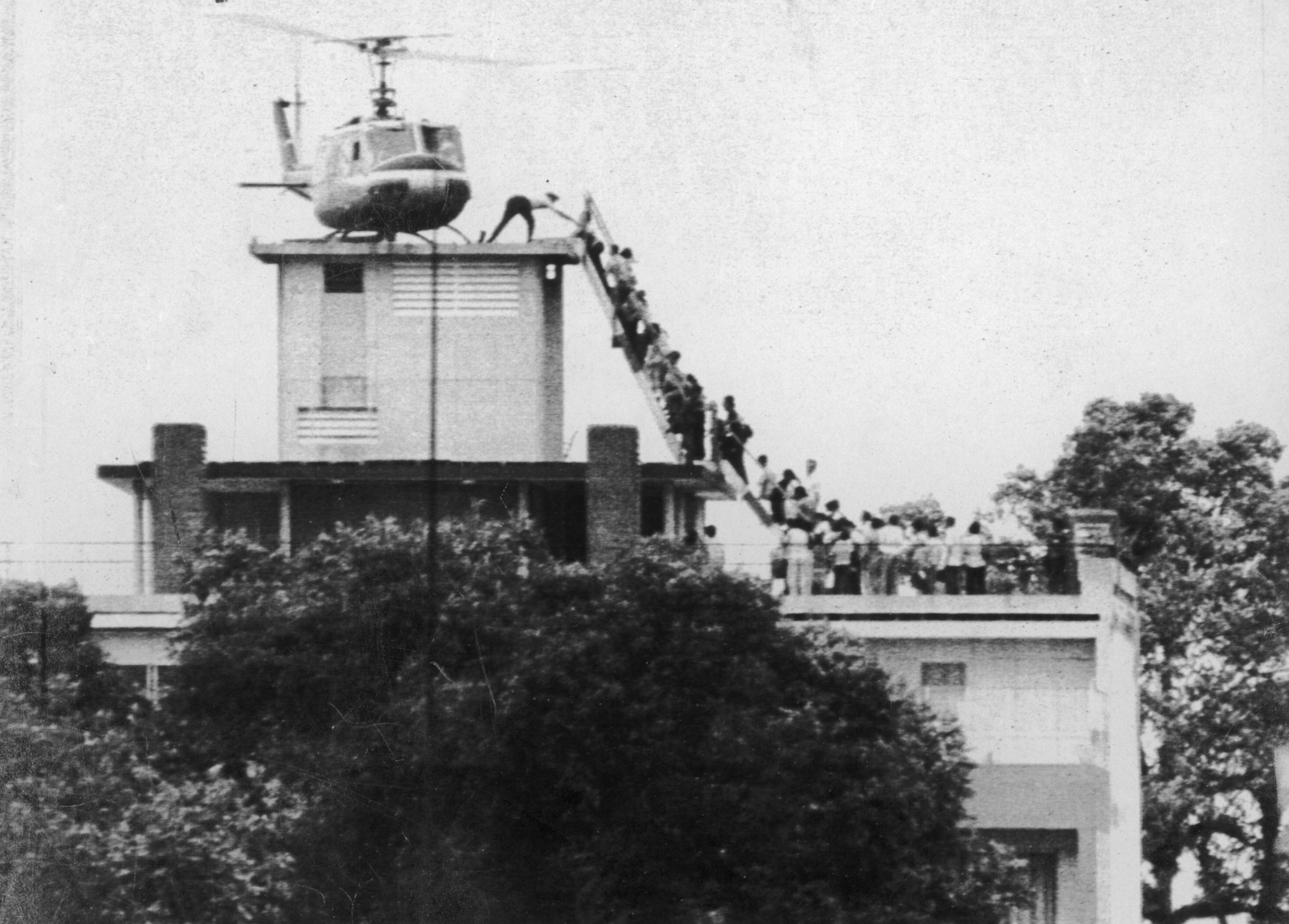

Nixon pushed for a peace settlement and “Vietnamization”—a complete turnover to the South Vietnamese. A ceasefire was signed in January 1973, and the last U.S. troops left in March. American funding to the South Vietnamese army soon decreased, and the Watergate scandal led to Nixon’s resignation in 1974. The Communists escalated their attacks, and the South Vietnamese soon realized that America was not going to come to her aid. On April 30, 1975, Saigon fell. The ultimate sacrifice paid by nearly 60,000 American boys had been for nothing.

***

To understand the Vietnam War through the eyes of those who fought, I called author and journalist Philip Caputo. From 1965 to 1966, Caputo served as a platoon commander in the United States Marine Corps in Vietnam, earning several medals—and as a journalist, witnessed the fall of Saigon a decade later. That same year, he was shot in the ankle by a militiaman wielding an AK-47 during the Battle of the Hotels in Lebanon as civil war raged across Beirut. He covered the invasion of Afghanistan by the Soviet Union, profiled the likes of William Styron and Robert Redford, and was a member of the writing team that won a Pulitzer Prize for uncovering election fraud in Chicago. His memoir of Vietnam, A Rumor of War, was published in 1977. It is now regarded as a classic of war literature and sold over two million copies in fifteen languages. It is a bruising and magnificent read.

Caputo joined the Marine Corps as a young and idealistic kid who imagined himself as one of the American knights-in-shining armor of JFK’s Camelot—albeit with a young man’s lust for adventure, combat, and violence. In Rumor of War, he describes the first years of American involvement, noting that the soldiers often felt like they were commuting to a war, with soldiers lounging about the base camp 90% of the time, fighting off the heat by day and the bugs by night before getting dropped into an LZ by Huey helicopters to wade through the jungle where the heat was a living, malevolent force and the sheer impenetrability of the jungle awoke ugly fear in the bravest of soldiers as they moved blind through the foliage. There were no real military objectives in the traditional sense, just geographical locations to get to. The objective was to kill some Viet Cong along the way—the orders from above in what would increasingly be a war of attrition were brutal and simple: “If it’s dead and it’s Vietnamese, it’s a Viet Cong.” It is a sad irony that the love that the men felt for their brothers in arms was what actually led to some of the war’s greatest cruelties—Caputo saw men die to rescue the corpses of their friends, and some of the worst atrocities were committed in revenge for the loss of comrades.

Caputo joined the Marine Corps as a young and idealistic kid who imagined himself as one of the American knights-in-shining armor of JFK’s Camelot—albeit with a young man’s lust for adventure, combat, and violence. In Rumor of War, he describes the first years of American involvement, noting that the soldiers often felt like they were commuting to a war, with soldiers lounging about the base camp 90% of the time, fighting off the heat by day and the bugs by night before getting dropped into an LZ by Huey helicopters to wade through the jungle where the heat was a living, malevolent force and the sheer impenetrability of the jungle awoke ugly fear in the bravest of soldiers as they moved blind through the foliage. There were no real military objectives in the traditional sense, just geographical locations to get to. The objective was to kill some Viet Cong along the way—the orders from above in what would increasingly be a war of attrition were brutal and simple: “If it’s dead and it’s Vietnamese, it’s a Viet Cong.” It is a sad irony that the love that the men felt for their brothers in arms was what actually led to some of the war’s greatest cruelties—Caputo saw men die to rescue the corpses of their friends, and some of the worst atrocities were committed in revenge for the loss of comrades.

“As an infantry officer, my experience was traumatically different than that of a pilot,” Caputo told me. “Infantry combat is immeasurably more intimate. But nevertheless there are moments in combat amidst the terror of it, the pain of it, the sheer misery and boredom of it—believe it or not, it can actually get boring—there are moments almost like a drug-induced ecstasy. You’re totally out of yourself, you don’t give a s**t if you’re going to live or die, you’re totally focused on winning whatever firefight or battle you’re in, and it is enjoyable. Enjoyable may be something of a weak or mild word for it. But I know when I started writing A Rumor of War, the most difficult things I had to contend with were my own memories of those moments when I really liked it—and that I missed it. Not only the almost transcendent excitement of combat, but also the brotherhood, the comradeship, the camaraderie. I probably missed that even more, because it’s something we all seek in life, to be united in a common endeavour. That was a very hard thing for me to come to terms with, mostly because I’d been raised a good Catholic boy and you’re not supposed to like being involved in something that involves killing people. I had a hard time reconciling that in my own mind. I can’t say that I ever reconciled it. It just happens to be one of the ambivalent realities about war.”

Caputo experienced his first firefight in April of 1965. “We had landed in this LZ [Landing Zone] out in the jungle. We took a few rounds of small arms fire coming in, but nothing too serious,” he recalled. “We disembarked from the helicopters and spread out. I was supposed to lead my platoon across a stream or river in a kind of enveloping movement of this hill. A messenger came from the company commander that I was supposed to turn around and get back. Just as I was doing that, I heard small arms fire. One of our other platoons had come under fire from a Viet Cong unit up on top of a ridge and they were exchanging gunfire. Just as my platoon got there, I saw the first platoon assaulting up the hillside and the company commander told mine and a third platoon to circle the ridge to try and trap the Viet Cong. I remember this sense of confusion, but that gave way to excitement, almost like at some athletic event. As we circled around the ridgeline, the firing slacked off, and I found that we were slogging through this awful swamp—and then excitement turned into this grisly horror. I was tacking through some brush and had my pistol out, and almost stepped on this dead Viet Cong who had been shot through the abdomen. His intestines were hanging out. I almost shot him again. My memories of this are first confusing, then exciting, and then horrifying—that all probably took place inside of fifteen minutes.”

Grisly horrors soon became mundane. “After I’d been in Vietnam for awhile, the abnormality of battle became the new normal for me,” Caputo told me. “Things that probably would have disturbed me earlier and perhaps disturbed me later did not disturb me in the moment. I do recall—I must have been in Vietnam ten or eleven months by that time—some kid, this trooper in my platoon—they’d killed some VC and cut the ears off them as trophies, which was a custom from these Chinese mercenaries who fought for the special forces. I remember being bothered by that straightaway. In the case of people killing each other, mutilating corpses, laughing at things that aren’t at all funny—the visceral and the moral become entwined. I remember a gunnery sergeant telling me that his platoon had been in this nasty little firefight and killed several Viet Cong and when it was over, they broke for chow. They took their C-rations out, and he heated his C-rations on the corpse of a Viet Cong that he used as a table. Not viciously—he told me years later that he did a thing like that as if it was perfectly natural, but it bothered him after he returned to normal life.”

In the final section of Rumor of War, titled “In Death’s Grey Land,” Caputo describes being reassigned to head up a rifle company, fighting a series of deadly skirmishes marked by snipers, boobytraps, and bloody fighting. After one operation, troops under his command killed two young men suspected of being Viet Cong. Caputo took responsibility for the killings and was removed from his command, facing a court-martial. He was eventually cleared and received an honorable discharge, but he told me that the incident, “quite candidly haunts me to this day. I will never forget it, because as I describe in the book, it wasn’t so much the literal orders I gave as much as the manner in which I gave them. That was interpreted by the troops as permission to go ahead and do whatever they felt like doing. At that time our company had suffered quite a few casualties. In less than a month, we had forty dead and wounded out of an initial strength of 140 or 150. I was just in full warrior mode. I wanted to kill these guys. Not just those two, but wipe out the Viet Cong in the area we had responsibility for. I was in a dark place. When I came out of it, I kind of looked back on myself almost as if I’d become a stranger to myself. I can’t describe it any better than that.”

Ten years later, Philip Caputo was back in Vietnam—but this time, as a journalist, covering what would become known as the Fall of Saigon. Those covering the events, Caputo told me, could feel it coming. “There was a sense that the inevitable was finally happening. There was quite a bit of confusion that emanated from the American ambassador Graham Martin who just could not, in his own mind, accept that the North Vietnamese were going to conquer Saigon and thus the South and would result in the loss of the war by the United States—the first war we had ever lost. He kept putting off measures to evacuate American civilians, Vietnamese workers, and embassy personnel. He took such a long time that when the end finally came, it was doubtful for several hours whether we were going to get out of there at all. I kept thinking about the guys I knew who had been killed in the war years before and realizing that they had died for no good reason. I was simultaneously angered and depressed by that. That was definitely with me when I finally did get on the helicopter. We got on the choppers under fire. North Vietnamese shells blowing runways up, small arms and missile fire. When we finally did cross the coast and I saw the Seventh Fleet out there, other emotions turned into immense relief.”

Toward the end of our conversation, I asked Caputo a question I’ve asked many veterans: If you had to do it over again, would you? His response was immediate. “Yes, I would. Primarily because of the way I’m constructed. I could not bear the idea of other men taking risks with their own lives while I sat back in comfort. I would have to share the dangers and the hardships with them. I couldn’t do otherwise. Beyond that, when I look back on it, I feel that I died and was reborn in Vietnam, to the point that a lot of my memories of my life before Vietnam are so vague, much vaguer than those of my contemporaries who did not go there, that it almost seems like those were the experiences of somebody else. Whatever I am now, whoever I am, was born in the war and out of the war. I think, with the caveat that I got out of the war with my mind and body intact, that I am a stronger, wiser human being than I would have been had I not gone there.”

***

Another Vietnam veteran, H. Lee Barnes lives in Las Vegas, Nevada, where he teaches English and creative writing at the College of Southern Nevada. Amongst veterans, he is a renowned novelist and short story writer who captures the experience of combat like few other authors, and his Vietnam memoir When We Walked Above the Clouds is a powerful and gut-wrenching read. Barnes was a Green Beret, and his first experience with combat was the civil war in the Dominican Republic in 1965. “It prepared me in many ways for Vietnam,” he told me, “because when we left the airport in Santo Domingo, we came under fire with the 50 calibres the rebels had over there, and it kind of immunizes you to the idea of being under fire. You don’t lose your head. You go on with the mission. That, and seeing bodies lowers your threshold for sensitivity to what you’re doing and who else it involves.”

Initially, Barnes was going to be headed back to the Dominican Republic. He was in Spanish language school at Fort Bragg as his friends prepared to ship out to Vietnam, and as those he trained with headed into the conflict, he decided to join them. “I was anticipating having an experience that I knew would shape the rest of my life whether I stayed in the military or got out,” Barnes told me. “I just had to do it. I felt a personal obligation to serve. You’re in an elite unit—certain things are expected of you and you expect certain things of yourself. One of them is you don’t want to retire at 65 or 70 and think that all my friends that I lost over there—I could have been there, and helped in some way. Of course, that’s ridiculous, but when you’re 19 or 20 years old you’re not fixed on the right star all the time.”

It was hot and humid when Barnes arrived in Vietnam in early 1966. “I got off the plane at 185 pounds and felt like I weighed about 200 pounds upon hitting the ground,” he recalled. “There were these body bags that they were getting ready to send back. I’d already seen dead bodies, but when you see them wrapped in body bags, where there’s no real identity to them—they’re just a faceless piece of meat on the tarmac ready to go home—that kind of hardens you. A lot of it seems mundane in retrospect because you have certain duties to perform in the camp, and for the sake of your teammates everybody has to pull their load and if it means you have to do menial tasks you do them. There were two or three firefights that I didn’t even mention in my memoir because I didn’t want it to be another memoir where there’s this kid of self-praising heroism.”

Barnes remembers his first firefight vividly. “The first time I came under fire in Vietnam I was prepared for it in such a way that I didn’t react to it in any emotional sense,” he told me. “I just simply looked at the target area where I would have to fire, kneeled down, and fired. I don’t remember how many rounds I fired, but I fired carefully. I didn’t fire off in three round bursts or anything like that; they were all single shots fired in the direction of where I saw the gunfire coming from. In that first instance the shooter was a sniper who was well protected by rocks up on the side of the mountain. Even to me it was as if you’re watching yourself do this—you’re an active participant, but you’re also an observer of your own actions. As you’re doing that, you’re still fully concentrated on your target area. We went down to engage the snipers so that we could weed them out, get them exposed so we could bring down an air strike on them.”

To this day, Barnes says, many of his memories are blocked. Speaking to fellow vets years later, they told him stories he could not recall—such as his suggestion at one point that they “frag” a sergeant whose incompetence was getting people killed. The drinking was out of control, he recalled, but he saw no marijuana or heroin in the special forces. He lost four of his comrades. “They didn’t die for a noble cause, but that doesn’t mean they didn’t die nobly,” he told me. “I think that the American press and the media and the anti-war movement tended to view us as animals because they didn’t approve of the war—that diminished the actions of the men there. I don’t think we should diminish their actions in any way. They did it in the service of their country nonetheless.”

It was the friends he served with that made him write his memoir—their stories. “You hear gunfire in the distance, you hear it intensely for awhile, it becomes sporadic,” he told me, his voice distant as he remembered. “You’re there in this intense state, wondering what’s going on out there, more worried about them than you are about yourself. The next day, before the unit came out to help us recover our dead, Norwood [a comrade] and I went out and some of the Vietnamese dead were strewn about there on the edge of the huts. On the edge of the road there were these two women who were over this dead body, moaning and screaming. If you hear the wail of a mother like that, it never goes away, and you understand that’s probably the same experience mothers have had since the dawn of time, since soldiers went out and fought and didn’t survive. The mother lost a son, lost a child. There’s something universal about that.”

***

As massive social movements erupted on American streets and around the world, Vietnam became a flashpoint for distrust of all authority, especially with the revelations of the Pentagon Papers, followed shortly thereafter by Watergate. Just as authorities and institutions were in desperate need of moral authority, they found themselves with none. The Vietnam War was far more complicated than “they lied, kids died,” but their moral credibility had evaporated all the same—just as revolutionaries were slamming themselves against an open door. If the authorities were wrong on Vietnam, the hippies demanded to know, what else might they be wrong about? And what else might they be lying about? The ordinary, blue collar Americans of the “Silent Majority” pushed back, repulsed by the upending of norms, the burning of flags, and the sheer weirdness and immorality of the counter-culture that was emerging across their nation. A disparate group of differing movements with distinct goals were galvanized by Vietnam, and it transformed America in a few short years.

“The Vietnam War shaped that whole era,” Philip Caputo told me. “This would include the Civil Rights movement, the feminist movement, the environmental movement, the questioning of institutions of authority. A lot of the divisions we’re now seeing—the Trump impeachment hearings being a glaring example of it—the divisions in America that have existed as a result of the Vietnam War, between the anti-war movement and the Silent Majority, have now spread like cracks in a windshield. It starts off with a single crack, and you end up with a spiderweb. I think our divisions can be traced back to that.”

Caputo believes that the war changed American society permanently. “It was the epicentre of a social and cultural earthquake,” he explained. “There was a loss of faith in institutions, particularly in governmental and military institutions that eventually spread to other institutions, even universities. If you’ve studied that era, you’ve read about all of the campus protests—the anti-war warriors, as I call them, taking over university presidents’ offices and actions like that. The loss of faith in and cynicism towards institutions that still exists can be traced back to that. The country reached a stage of maturity during the ‘60s when people began to question things that had not been questioned before.”

In short, the Vietnam War was the backdrop against which America convulsed through an astonishing cultural revolution, followed by a conservative backlash that would shape the rest of the century.

***

As is so often the case in great conflicts, the ordinary folks who fought are often forgotten amid the sound and fury of escalating politics. This was especially true of Vietnam, as returning veterans often face ugly jeers and scorn from Americans at home who opposed the war. Many would never forget the way they were treated when they completed their tours of service, and many carried bitterness over it for the rest of their lives.

Every so often, we are reminded that many of those who fought in Vietnam are now elderly men. America’s most famous Vietnam veteran, John McCain, died several years ago at the age of 81 (and Philip Caputo, who knew and loved him, told me that he has not forgiven Donald Trump’s disparaging comments about McCain’s service.) It is strange to consider that the veterans of Vietnam are now as old as World War II vets were when we were young. Perhaps it is because Vietnam still seems so fresh.

Some time ago, I spotted an obituary in The Dickinson Press for a veteran of Vietnam. It perfectly encapsulated what so many of them endured, and the price they had to pay long after their service ended:

“Not everyone who lost his life in Vietnam died there.” The saying is true for CW2 William C. Ebeltoft. He died on December 15, 2019 at the Veteran’s Home in Columbia Falls, Montana. He died 50 years after he lost, in Vietnam, all that underpinned his life. He was 73 years old.

Everyone called him “Bill.” He was loved by the nursing staff who cared for him. He was loved by the fellow veterans with whom he lived; those he helped when he was able and entertained with funny German slang and a stint at the piano when he could. He was a virtuoso when playing “Waltzing Matilda.”

His small family loved him dearly. He was preceded in death by his parents, Paul and Mary Ebeltoft of Dickinson, North Dakota, whose devotion and care for their war-damaged boy was strong and unfailing. He is survived by his brother, Paul Ebeltoft, and the one he loved as the sister he never had, Paul’s wife, Gail. Both live in Corning New York. They will miss him every day. He is also survived by his nephews, Robert Ebeltoft of Brooklyn, New York and David Ebeltoft of Corning, New York. They both found Bill to be quirky, “old school,” soft hearted and generous. They valued their time with him and would have loved to have more, as would all who knew Bill well.

It is difficult to write about Bill. He lived three lives: before, during and after Vietnam. Before Vietnam, Bill was a handsome man, who wore clothing well; a man with white, straight teeth that showed in his ready smile. A state champion trap shooter, a low handicap golfer, a 218-average bowler, a man of quick, earthy wit, with a fondness for children, old men, hunting, fast cars, and a cold Schlitz. He told jokes well.

During Vietnam, he lived with horrors of which he would only seldom speak. Slow Motion Four, Bill’s personal call sign, logged thousands of helicopter flight hours performing Forward Support Base resupply landings, medical evacuations, exfils and gun ship runs. We know of him there mostly through medals for valor he received, and these were many. The following is quoted from but one of these, recording events that occurred on February 3, 1969. “While acting as aircraft commander of a UH-1H helicopter, WO Ebeltoft distinguished himself when his ship came under heavy automatic weapons while on a resupply mission for Company B, 1 Battalion, 52 infantry. While attempting to resupply B Company, WO Ebeltoft’s co-pilot became wounded. Realizing the importance of the mission WO Ebeltoft elected to attempt completion of the mission. Due to his superior knowledge of the aircraft, the helicopter was kept under control during the period in which the pilot was wounded and the ship was under fire. Remaining under attack from automatic weapons fire, the supply mission was successfully completed. While unloading the supplies, WO Ebeltoft received word that there were five emergency medical evacuation cases located 200 meters to his rear. WO Ebeltoft re-positioned his helicopter and picked up the wounded personnel. While evacuating the wounded, the commanding officer of Company B was injured. WO Ebeltoft again maneuvered his aircraft to enable evacuation of the injured officer. WO Ebeltoft then proceeded to evacuate all injured personnel by the fastest possible means. Upon completion, examination of the aircraft revealed that the craft had sustained nine enemy .30 caliber hits.”

Bill got the medal, of course, but he would have been the last to say anything about it. The citation shows the type of man that he, and many of his brothers-in-arms in Vietnam were; and still are today, albeit battered hard and unfairly by the cruel winds of the times in which they fought.

After being discharged as a decorated hero, Bill had a rough re-entry into civilian life. It is not necessary to recount Bill’s portion of what is an all-too-common story for wartime veterans, particularly those of the Vietnam era. It may be sufficient to say that after a run at business, a marriage and while grappling daily with his demons, his mental faculties escaped him. Bill became a resident of the Veteran’s Home in Columbia Falls, Montana in 1994. He lived there for the next 26 years.

At the Home, the patina of his memory covered life’s sorrows, and it was a blessing. Bill was happy there, living a life that was a strange mixture of hunting stories, pickup trucks and memories of some of his better times with women, friends and the outdoor life. Bill denied that anyone he loved had died; could not understand why anyone would fill with gas at four bucks a gallon when “Johnny’s Standard sells it for 27 cents;” and still “drove” his 1968 Dodge Charger. He was unfailingly courteous. His largest concerns were making his smoke breaks and finding his wallet (a search of 26 years).

In the past year, Bill’s shaky grip on physical health also slipped through his fingers. Yet, despite this, what we loved in him remained, if only sometimes as a shadow. Even after his serious decline, suffering fractures because of falls, Bill would tell the staff that he was “just fine” and not to worry about him. Thin, hunched over, propelling himself with one foot, he would wheel himself into the room of a bed-ridden veteran and sit there, next to the bed, unspeaking. The nursing staff was certain that Bill thought that the man in the bed was lonely and needed company.

Bill was always a proud man, remembering himself as he was in 1969, not as he became. Who are we to suggest differently? His was not a life that many would wish for, but in some ways, Bill was a lucky man. He was surrounded to the end by staff who enjoyed and respected him. He had a chance to be helpful to others who were doing less well than he. And the passing of the seasons never diminished his plans for another elk hunt or to “see that beautiful girl again this weekend.”

When a small slice of reality penetrated his pleasant confusion, Bill struggled to understand why he was where he was. Prematurely aged, his worldly goods in a small dresser, not knowing who the President might be or remembering why he should care, Bill’s losses were greater than most of us could endure. Yet, to those who love him, his brother and his brother’s wife, and their sons, he will always be a brave, accomplished man, more generous than was wise, more trusting than was safe.

It is not possible to wrap your arms around a loved one who leaves. But it is possible to wrap your heart around a memory. Bill’s will be well taken care of.

Historical memory is the duty of every citizen, and to remember the Vietnam War is not only to remember those who served—it is to begin to understand why things are the way they are.

That was an awesome article, Jonathan. Brought back a lot of memories of the 70’s when I was just a young woman. Had I been an American living in the US, I would have been a part of the Vietnam protests, even though I really didn’t understand US politics. But hey, we were young and impressionable and it seemed so romantic to be fighting for something. Those years were both disconcerting and exciting all at the same time. However, for those that fought in the war and needlessly died and for all the vets who returned broken men, the obituary said it all, “Not everyone who lost his life in Vietnam died there.” For those who lived through it, they will never forget it.

Thank you, Barbara!

Do you know who are all the men are in the photos?

No.