Blog Post

Gloria Steinem and abortion as a feminist sacrament

By Jonathon Van Maren

This column was first published at The Stream

It has been a good year for 86-year-old Gloria Steinem. In April, the miniseries Mrs. America portrayed her as the beautiful nemesis of a fictitious evil Phyllis Schlafly. Steinem was young, idealistic, gorgeous. Schlafly, on the other hand, was a relic of another era, viciously fighting progress. In September, Hollywood’s latest hagiography arrived. The Glorias, directed by Julie Taymor, has a simple thesis: Gloria Steinem is one of the 20th century’s great heroes.

After a few affecting scenes early in the film — most portraying Steinem’s tender relationship with her father — the point of the biopic soon becomes apparent. This is another election-year abortion movie. Taymor isn’t even subtle about it. For the second time this year, the 1957 death of Steinem’s child is memorialized onscreen. “I can’t have this baby,” she tells abortionist John Sharpe. He famously makes her promise two things. First, that she would tell nobody his name. Second, that “you will do what you want with your life.”

An easy choice. Steinem has the abortion. The film flashes to the next scene. She comes out as feminist to her editor. She demands permission to write about abortion. He refuses. In the next scene, she is climbing a stage to give her first speech in Washington, D.C. A baby dies. A feminist is born. A baptism of blood. The only complaint Steinem has is that it should have been so much easier. Not once, The Glorias makes clear, has she ever regretted it.

Time and again, The Glorias drives home a simple point. You, too, can grow up to be beautiful, talented, independent, and successful. All it will cost you is your children. Feminists with children in the film flame out. Steinem struggles with a personal issue. But it’s not her abortion decision. Instead it is this: Why didn’t she ever ask her depressive mother why she didn’t leave her Gloria’s father after the birth of her older sister, to take up journalism again? Because you wouldn’t have been born! her younger self reminds her. Steinem responds to herself: I wouldn’t have had the courage to say to my mother: No. You would have been born again.

Steinem doesn’t quite sneer at her mother’s sacrifice, but close. She certainly doesn’t understand it. By leaving her father and not giving birth to her, her mother could have been “born again” — as an independent woman. Why should Steinem celebrate the tireless sacrifices of millions of mothers? She has unashamedly celebrated her abortion as a life-defining event (Her 2015 memoir, My Life on the Road, is dedicated to the abortionist). The film emphasizes her fascination with Gandhian non-violence, but Steinem’s feminism isn’t non-violent. Her child never got what Steinem’s mother gave her: A chance.

The film also portrays the first abortion rights marches (fusing them with real footage). The release of Ms. Magazine in 1972 was accompanied by a list of 53 prominent American women and the simple headline: “We Have Had Abortions” (The year before, 343 French filmmakers, actresses, singers, philosophers, and writers had done the same thing in Nouvel Observateur). The famous anecdote of a female cab driver in New York City telling Steinem that “if men could get pregnant, abortion would be a sacrament” is of course included.

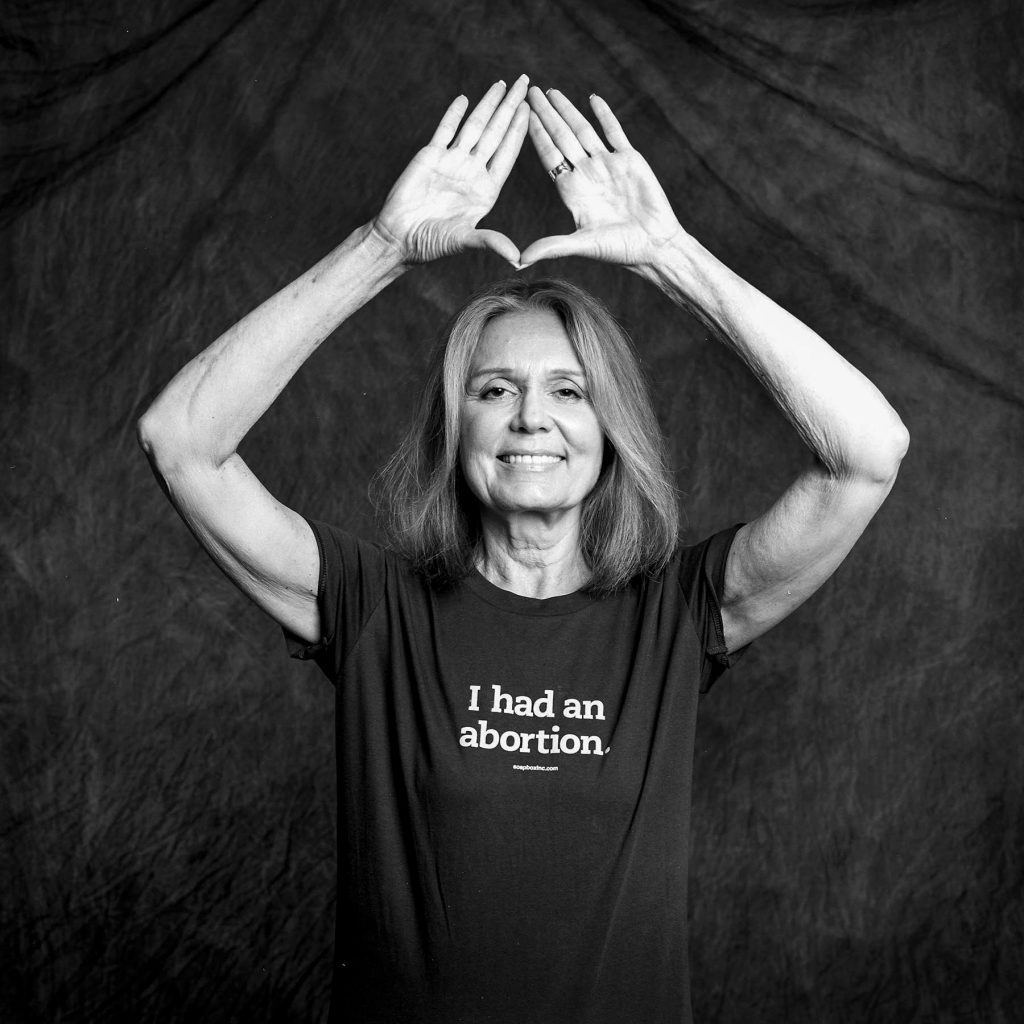

In one scene, Steinem explains her position to a Hispanic labor leader, a Catholic and mother of a large family: “Nobody in their right mind is pro-abortion. It is a method of last resort.” That is nonsense. Steinem herself has joined “Shout Your Abortion” campaigns, doing a photo-shoot with a t-shirt reading “I had an abortion.” When I attended the Women’s March in 2017 (the film closes with Steinem’s speech there), I saw her sitting onstage next to a woman wearing a sweater with “I *heart* Abortion” written all over it. I was in the crowd as thousands of deafening cheers rose up every time Planned Parenthood was mentioned. Steinem is pro-abortion, and so are her fans.

The requisite slander of the pro-life movement, of course, was front and center. The Catholic mother is immediately convinced by Steinem’s trite lies. Now that you say it, she nods, when I went to join the right-to-lifers (led by Phyllis Schlafly), I saw the Klan, and the same angry right-wingers who hate us. As for religion? “I don’t want to go against the Church, but we have to think of ourselves first. What do they do for the child after they’re born?” A lot, of course.

But nuance has no place in propaganda intended to canonize Steinem before she dies. In another scene, Steinem is portrayed as a sobbing little girl in the back of a car while pro-lifers scream through the windows, their faces contorted with hate.

The Glorias is another film in the ongoing recreation of America’s founding stories. America’s heroes are no longer the Pilgrims, those who settled the West or any of the other wicked folks whose statues are being pulled down. Instead, they are the sexual revolutionaries who started us on the road to progress. Sex criminal Alfred Kinsey was lionized in Kinsey (Liam Neeson). Statutory rapist Harvey Milk got Milk (Sean Penn). Gloria Steinem got Mrs. America (Rose Byrne) and The Glorias (Julianne Moore). And the list goes on.

These films are shot through with American imagery (The Glorias begins in a biker bar). The Sexual Revolution is America’s new origin story. It is no longer man and woman against wilderness, it is man against woman. Woman against child. The revolutionaries versus the reactionaries. The Past versus the Future. This is a recasting of America’s history with new heroes and new ideologies, told to a largely ignorant public by powerful Hollywood storytellers. As Mary Eberstadt reflected recently, it won’t be long before there will be nobody left who remembers life before the Sexual Revolution. And then, we’ll be left with their version of the story.

I’m not saying the sexual revolutionaries shouldn’t be humanized. I’m saying they shouldn’t be lionized. Nor should their opponents be demonized. When sexual revolutionaries have flaws, it turns out, they are endearing, understandable, carefully contextualized (if mentioned at all). When those who fought the revolution are portrayed, they are wicked, irredeemable — standalone black sheep who are not products of their time, but products of their own inherent evil. We still have saints and sinners, you see. The roles have simply been reversed. Evil is easily made glamorous on film. Stolid virtue is more difficult.

The Glorias is another contribution to the canonization of Gloria Steinem. She has become a living icon. I’ve seen her photos in museums alongside those of Martin Luther King Jr. and Gandhi. King freed African Americans from segregation. Gandhi freed the Indians from colonial rule. And Gloria Steinem helped free both men and women from their children and from sexual responsibility.

She’s still here, and her carnivorous movement is not finished. The Glorias is a reminder to all those still battling the Sexual Revolution that this is far from over. It is a reminder that the revolutionaries unleashed poison on America. And it reminds us that our children and our families are worth fighting for.