Blog Post

Norman Rockwell and William Kurelek on abortion

By Jonathon Van Maren

Many artists have grappled with how to depict abortion. Ernest Hemingway wrote an entire short story about abortion, and poets like Gwendolyn Brooks and Anne Sexton have composed some truly brutal lines about their own experiences. Many musicians have channeled their pain and loss into powerful lyrics. But in the visual arts—aside from film—abortion has been almost entirely absent. Taken together, works by two remarkable painters—American Norman Rockwell and Canadian William Kurelek—show why we urgently need more artists to expose the mass murder of the unborn in our society.

By the time he died in 1978, Norman Rockwell had produced over 4,000 original works and was likely the best-loved American painter ever. In his paintings were swimming holes and church services, Thanksgiving dinners and farewells, sports games and awkward dates, personal prayers and political events. Rockwell documented Americans and their everyday lives at their best, creating timeless scenes that spoke directly to the core memories of his audience. In fact, Rockwell’s art became so popular that he helped to shape America’s collective consciousness, holding up a mirror to the high drama of ordinary living. “Without thinking too much about it in specific terms, I was showing the America I knew and observed to others who might not have noticed,” Rockwell once said of his work.

Rockwell was also capable of darker art. His 1965 painting Murder in Mississippi is a chilling rendering of the 1964 murders of civil rights workers Michael Schwerner, James Chaney, and Alan Goodman. Klansmen had shot them point blank and pushed dirt over their corpses with a tractor. The painting shows a bloody James Chaney slumped in the arms of a colorless Klansman with another young man dead or dying next to them. Rockwell’s more famous 1964 work The Problem We All Live With shows little Ruby Bridges being escorted to school by federal marshals, the wall behind them spattered with tomato juice and a racist epithet.

But when it came to abortion—that most intimate violence—Rockwell may have run dry. In her 2001 biography Norman Rockwell: A Life, Laura Claridge argues that one of Rockwell’s famous Saturday Evening Post covers likely has a chilling backstory. Claridge reports that according to one of Rockwell’s children, in 1938 the artist took Mary, his second wife (there were three), to England for an abortion. The Post cover for October 8, 1938—the first after the alleged abortion—is called Blank Canvas, and depicts Rockwell sitting in front of an easel with an empty canvas in front of him, scratching his head. On the corner of the canvas is a note: “DUE DATE.” According to Claridge, this emptiness represents the loss of the aborted Rockwell baby. There was no child to lovingly render—the child was gone, and Rockwell could not (or would not) paint his bloody demise.

William Kurelek, who would become known as “Canada’s Norman Rockwell,” was born in a prairie shack during the winter of 1927. He grew up working the land and tending the livestock on his parents’ Albertan grain farm. He discovered his talent for drawing early on, covering his bedroom walls with vivid sketches. In 1946 Kurelek headed to the University of Manitoba, where he majored in Latin, English, and history. He also began to grapple with the mental illness (professionally undiagnosed) that would afflict him his entire adult life.

In his youth, Kurelek worked in Edmonton as a roadbuilder, in Quebec as a logger, and in Toronto’s Royal York Hotel as a waiter, with brief stints abroad in Mexico (to study art) and England (for psychiatric care). By 1954, Kurelek’s mental struggles drove him to religion. His close friend Margaret Smith, an occupational therapist and devout Catholic, led the way. He sought out spiritual instruction, took several correspondence courses on Catholicism, and ultimately joined the Guild of Catholic Artists and Craftsmen. (His 1955 painting Lord That I May See encapsulated his struggle.)

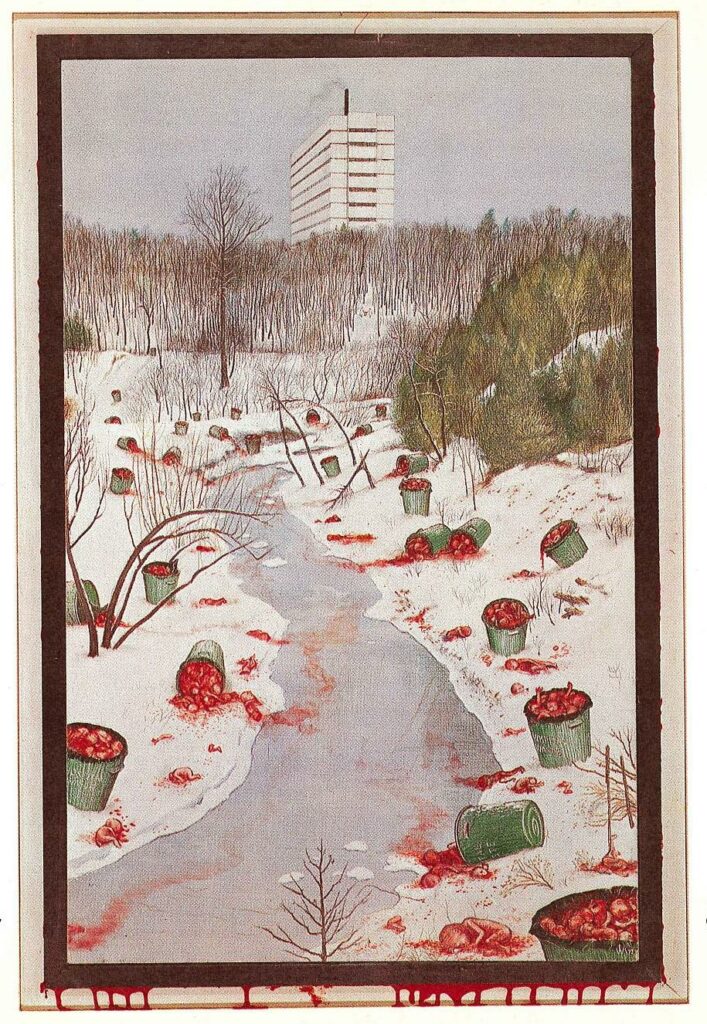

Over the ensuing two decades—Kurelek would die of cancer at age fifty—he produced more than 2,000 paintings and drawings and became one of the most successful artists in Canadian history. His childhood on the prairies, his young adulthood in the logging camps, his travels across Canada—these became simple, evocative scenes that would capture the hearts of millions and turn him into Canada’s preeminent visual chronicler. But Kurelek also boldly tackled abortion.

READ THE REST OF THIS ESSAY AT FIRST THINGS