Blog Post

The paradox of Franky Schaeffer

By Jonathon Van Maren

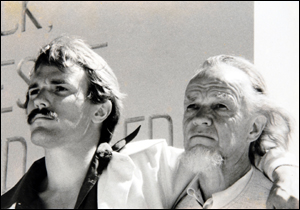

Times seem dark for American conservatism. With the Republican Party engaging in a bloody, full-fledged civil war, the House of Clinton slowly rising once again, and the potential of Barack Obama stacking the Supreme Court with progressive justices for a generation, politicians constantly conjure up the smiling, sunny face of Ronald Reagan to harken back to a time when conservatism seemed to be on the perpetual rise. And so it did—the conservative movement’s darling was in the White House. Intellectual heavy-hitters such as the National Review’s William F. Buckley did battle with the left on stage and television. Dr. Everett C. Koop and Dr. Francis Schaeffer led hundreds of thousands of evangelicals into the pro-life movement, swelling the GOP’s Big Tent. These great men are gone now, and their legacies seem to be slipping away—and some of the conservative movement’s defectors bear names that ring familiar.

Ron Reagan Jr. Christopher Buckley. Franky Schaeffer. Three sons of three great icons of the American Right, and three men who decided that the path of the father was not going to be the path of the son. Ron Reagan Jr. is now a left-wing commentator who regularly criticizes conservative policies. Christopher Buckley, the son of the great William F. Buckley, wrote a column in 2008 titled “Sorry, Dad, I’m Voting for Obama.” And Franky Schaeffer, son of the activist theologian Francis Schaeffer, has been tossing rhetorical hand grenades at his father’s legacy almost since Dr. Schaeffer passed away of cancer in 1984.

When I asked Frank, who went by “Franky” during his evangelical days, why the sons of the great conservatives of the 1980s had each, for their own reasons, decided to repudiate the legacies of their fathers, he hedged at first.

“Well I think it’s a good point and I wouldn’t equate my work exactly with theirs,” he replied, sounding partially thoughtful, partially defensive. “The first thing I just want to do is put my own memoir in context and then remind me to get back to your question. I’d like to figure it out myself so we’ll talk about this. I have over a dozen books in print so the first thing I want to say is I write professionally, I earn my living and have since the publication of my first novel, Portofino…and the reason I want to note this is that it’s not like one day I woke up in my mid-50s and said ‘I want to write a tell-all book about my family.’ To my knowledge Ron Reagan and some of those folks, they’ve written a memoir to get something off their chest. They don’t earn their living as writers. I always fold my life into my books and I don’t know how to do anything differently. So when my son was in the Marine Corps I wrote a book about that. I’m interested in art and I’ve written about that. So I just want to say it’s not like I pulled this out of thin air and said ‘I’ve got to address this’ like it was a burning desire just to talk about this.”

That doesn’t strike me as quite true, at face value. For one, Ron Reagan Jr. has worked as a journalist and Christopher Buckley is an acclaimed novelist, so both have certainly made their living writing. And for two, Frank Schaeffer’s memoir of his parents, Crazy For God: How I Grew Up As One of the Elect, Helped Found the Religious Right, and Lived to Take All or Almost All of It Back is a sarcastic and savage read. There are tender moments in the book, to be sure, and many loving recollections of his parents Francis and Edith, but nearly every aspect of their careers is addressed with the vague insinuation that hypocrisy was pervasive. Francis wrote dozens of acclaimed works on theology and culture, from How Now Then Shall We Live to A Christian Manifesto, and hundreds of students learned at his feet in the religious community of L’Abri, Switzerland. It was at his urging that thousands of Christians entered the political arena to protest abortion. In some ways, he seems to have been too obvious a target for his writer son to resist.

Frank continued thinking aloud. “Now, having said that, to get back to your question, which is a great one. I think one of the reasons why people like me have moved away is for two reasons. First of all, obviously, as you get older, if you’ve grown up in a family with a powerful person as a father, you’re going to be folded into that family where you’re that kind of nepotistic sidekick for a while, maybe, but later you’re going to think about it in terms of what you believe yourself [and] what you want to do with your life. I think that’s a natural progression. But I think that in the case of my father, too, I wanted to set the record straight because I don’t think it’s fair that he’s been labeled as the leader of the Religious Right. Anybody who’s read Crazy for God who is not from an evangelical background, where they’re looking at him as a kind of a hero to their evangelical faith so they might be upset with me on that. I think anybody who just reads Crazy for God as a memoir or my new book, Why I’m An Atheist Who Believes in God, will very quickly realize that I not only love my father, I write about him very fondly but I also write about him as a real person.”

No one can deny that Frank loved his father. And yet what Frank seems to either misunderstand or steadfastly ignore is that his memoir casts a severely unflattering light on Francis—not because Frank was honest, but because he was contemptuous. Christopher Buckley, too, wrote a memoir about his parents William and Patricia Buckley—Losing Mum and Pup–but he manages to be truthful without being cruel. Os Guinness, now a renowned intellectual in his own right, lived at the Schaeffer’s religious community in L’Abri for several years, and was even the best man in Franky’s wedding. His analysis of Crazy for God was a somber one:

Frank Schaeffer unquestionably adored his father, just as his father passionately adored him. Having lived in their home for more than three years, I have countless memories of this, including the sight of the two of them wrestling on the floor of the living room of their chalet, and ending with a fierce hug. Yet no critic or enemy of Francis Schaeffer has done more damage to his life’s work than his son Frank—a result that one might not be able to infer from many reviews of the memoir, including that which appeared in the previous issue of Books & Culture.

The problem is not so much that Frank exposes and trumpets his parents’ flaws and frailties, or that he skewers them with his characteristic mockery. It is more than that. For all his softening, the portrait he paints amounts to a death-dealing charge of hypocrisy and insincerity at the very heart of their life and work. In Frank’s own words, his parents were “crazy for God.” Their call to the ministry “actually drove them crazy,” so that “religion was actually the source of their tragedy.” His dad was under “the crushing belief that God had ‘called’ him to save the world.” Because of this, his parents were “happiest when farthest away from their missionary work.” Back at their calling, they were “professional proselytizers,” their teaching was “indoctrination,” and it was unclear whether people came to faith or were “brainwashed” and “under the spell” of his parents. Frank’s own arguments in their support, he now says, were a kind of “circus trick.”

I asked Frank, bluntly, whether or not he felt that his memoir had a rather patricidal tone to it, and whether or not he felt there was any betrayal in some of the things he had written about his parents. He did not.

“I don’t think it’s unusual for a writer to fold the experiences of their own life into a book,” he replied, “and so people say, you know, why did you write that book in particular? And I can be very honest and say, listen, I’m a writer and if my dad had been a steel worker in Gary, Indiana, and I’d watched the decline of steel mills and I was setting either a novel or a nonfiction memoir there, if he came home at night and hit my mother or after he lost his job crashed the family car, that’s part of the story so yeah, it’s a great liability having a writer in the family who’s a serious writer because they are going to fold your story into their work and I certainly am in that sense. You can Google and you will find hundreds if not thousands of instances where family members, other people, complain bitterly as they’ve been pulled in these books. This is the business we’re in so…”

“Isn’t that sort of dodging the question?” I pushed, wondering if he might get irritated with me before the end of the interview.

“The real question is ‘Is it true?’” he interrupted. “And if something is true and actively sheds light on a period of history or a personality, you know, I think it’s very important that people who follow these prophetic figures, whether it’s Billy Graham or whether it’s my dad or whether it’s Pat Robertson or whether it’s Barack Obama–I’m not talking right or left–it’s very important that everybody understands that these are human beings and they have feet of clay, because there’s nothing worse than this kind of prophetic worshipfulness of leaders in a religious cause, somehow pretending that they’re not people. I think it sends the message which tells other people, ‘Look, these guys were either perfect or special.’ They’re not!”

But perhaps one of the reasons one senses a bitterness in the son of Francis Schaeffer is the cruelty with which he talks about his father’s followers. He refers to evangelicals as “village idiots,” “cult members,” “stupid people,” “racist,” and “not terribly bright,” just to mention a few. The left-wing hosts at MSNBC and Salon.com love to trot out Frank Schaeffer, the son who saw the light. His blog reads like the diatribes of a social justice warrior university student completing a degree in bitterness studies. So his critics can be forgiven for thinking that perhaps it is not simply a dedication to truth and creative integrity that directs the harpoon pen of Franky Schaeffer. After all, this is a man who insists that it’s unfair to lump his father in with the Religious Right crowd while claiming to be one of the founders of that crowd in the very title of his book.

But what surprises me when I talked to Frank is that he didn’t seem to take offense when I asked him tough questions—not even when I pushed him on them. When I asked him why he doesn’t oppose abortion from a left-wing point of view rather than condemning those who oppose abortion from a conservative point of view, he told me I had a good point and that he’d have to think about it further. When I asked him if he would be upset if one of his children wrote a memoir about him that was as scathing as his own book was about his father and mother, he replied that if the book was any good, then he wouldn’t mind at all. Not only that, but he began to list, out loud, what he thought some of his worst faults were and what sorts of incidents might make it into such a book. Frank Schaeffer may be many things, but brutally honest is certainly one of them—and he applied this honesty to himself as much as to those around him.

And when I ask him to talk about growing up in L’Abri, his confrontational tone dissipated somewhat. He talked about drug addicts hitchhiking to the commune to crash and get clean. He talked about Timothy Leary stopping by to debate the meaning of life. He recalled, with humor in his voice, that when he’d been working the lights at a concert hall Jimmy Page of Led Zeppelin had mentioned borrowing Dr. Schaeffer’s book Escape from Reason from Eric Clapton. And without the sarcasm, Schaeffer’s fondness for his family shone through.

For the final question of the interview, I decided to ask Frank how, in spite of everything he’d written, we should see the legacy of his father. What was the legacy of Dr. Francis Schaeffer, at the end of the day?

“Every day I take care of Lucy, Jack, and Norah,” Frank responded, referring to his grandchildren. “When I put on a piece of classical music, and I sit them down with pens and pencils instead of an iPad, and I reorganize my life around those children, what they don’t understand is that’s the legacy of my father and mother. They were compassionate people who really believed in doing what you said, and the fact that I grew up in a home like that means that my grandchildren meet my dad every time they see an open art book on the table instead of another piece of something from the Disney corporation. And what they don’t understand, you know, is my father’s legacy is a commitment to an idea of beauty in life that does not need justification and has intrinsic worth. And I would say what my dad’s real legacy is standing up for the intrinsic worth and beauty in both human relationships and creativity. And for that matter, the way he lived in practice of the Gospel with an open home and really caring for the stranger. This is his real legacy.”

For a moment, the name-calling, the contempt, and the sarcasm fall away, and the son’s admiration for the father comes through again. Dr. Schaeffer’s legacy is as relevant today as it was those decades ago. Frank may have rejected his father’s beliefs, but he cannot help but praise how those beliefs impacted his father’s life—and his own. I wondered, as I thanked Frank Schaeffer for taking my call, whether he was sorry he’d agreed to the interview. Then, he interrupted my thank-you.

“I wish every interview I did had questions that were this good and thoughtful,” he said. “You really do inspire someone to think hard when you ask real questions.”

And as I hung up, I shook my head at the paradox that is Frank Schaeffer.

Attention, and making a living. You politely call him a “Paradox”. Very kind. More like the guy wearing a sandwich board that rewad “Will Betray for a Buck… “