Blog Post

Immigration, Identity, and Islam: A conversation with Douglas Murray on the future of Europe

By Jonathon Van Maren

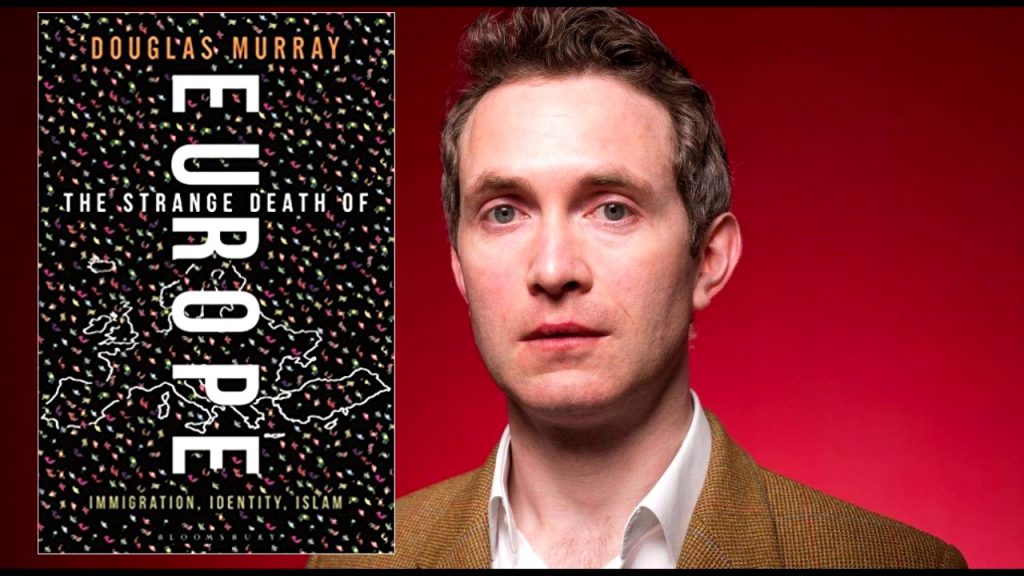

In all the noise and babble surrounding the slow and steady implosion of Europe, one clear voice consistently cuts through the din: that of Douglas Murray, who writes regularly for the Spectator as well as publications like the National Review, and as of late has appeared on stage as part of discussions with academics such as Jordan Peterson and Sam Harris. In my humble opinion, he is the best chronicler of the topics that form the subtitle of his 2017 book The Strange Death of Europe: Identity, Immigration, and Islam.

Murray’s work is not simply admirable because his writing is such a pleasure to read. It is admirable because he is so intentional about avoiding the booby-traps other commentators dealing with these prickly issues seem to fling themselves into with such vigor. He firmly states that we should be able to have a discussion about immigration and how much of it we want, while pointing out that those who decide to suppress such discussions with accusations of racism actually leave this terrain open for genuine white nationalists—and notes that it is always a terrible idea to allow bad people to have good points.

Murray’s The Strange Death of Europe takes its place among a handful of books on the subject of Europe and Islam that should be mandatory reading: Ayaan Hirsi Ali’s Infidel, Mark Steyn’s America Alone, and (for the Dutch perspective) Ian Buruma’s magnificent Murder in Amsterdam: The Death of Theo van Gogh and the Limits of Tolerance. Murray’s book, of course, is the most comprehensive, being the only one written after the 2015 migrant crisis that escalated and exacerbated the existing problems.

Douglas Murray was kind enough to join me by phone some time ago to discuss his book and the existential issues he attempts to tackle.

What prompted you to write this book?

I’ve been following the so-called migration crisis of 2016 both before that and after it, and this book is really the result of those travels and those attempts to get at what I regard as being the very deep questions that lie underneath not just this story, but the European continent at this stage in its history.

What surprised you in the process of this research? Your book seemed far more reasonable than much of the commentary on this topic because you tried to be brutally honest about the problem without demonizing leaders who did bring in refugees, even if their charitable feelings were at times misplaced.

Well, all sorts of things. I’ve been writing around these areas for many years, and so much of the groundwork I was familiar with, in particular the way in which, as I say in the book, there is no conspiracy to this, no grand scheme—it is rather simply the result of several generations now of European politicians putting off for their successors problems that they would rather not deal with themselves because they’re too difficult. But I suppose if there was one thing that surprised me it was the sheer extent of the consequences of the events that unfolded at such incredible speed in 2015 but which had been going on for many years before. This is a year where up to 1.5 million entered Germany alone. Sweden and Germany added almost 3% to their populations that year. And the sheer variety of human misery, among other things, that this entailed, surprised me, to the extent that one can still be surprised about these things.

But what also surprised me in some ways is that there was so little desire, in the places that I went to and in the politicians that I spoke to—politicians who were from across the political mainstream—I was amazed at the lack of willingness to recognize the scale and the depth and the extent of the problem. So many politicians—and I know this will be familiar—are very, very fearful of tomorrow morning’s headlines. And the easiest way, when it comes to the migration crisis of 2015 and the runup to it and the years that have followed, the easiest thing is to avoid bad headlines tomorrow. We now know that one of the reasons Chancellor Merkel decided to suspend normal border procedures on the last day of August 2015 is because she didn’t want photographs going round the world of German border guards repelling migrants.

Now as I say, this is very understandable in the short term, but I was amazed at the lack of thought from the chancelleries of Europe about what all of this would mean in the long run.

You’ve been covering this a long time, and you’ve said that one of the first things that you started to notice was the treatment of Jews.

One of the presumptions that’s prevailed in Europe in recent years is that effectively when people come into our continent—I’m from Britain, as you can tell, but I think of it as our continent—that they basically absorb the values of Europe, that they become like us. I think this can happen, but it’s not as common as people think or hope, and the opposite is also the case. There are a lot of people who have frankly no likelihood of becoming European, or, to put it a different way, they run the risk of repeating the mistakes that Europeans have themselves made in the past.

One of the examples I give is with the extraordinary phenomenon of an increase in anti-Semitism across the continent, which has undoubtedly derived from the recent arrivals. This phenomenon is one that is so sensitive that all officials always deny it until the point when they can deny it no longer. That happened at the end of my book—I describe one German minister, the interior minister of Germany, who says after they’ve already opened the doors to people from the Middle East, from sub-Saharan Africa, North Africa—he says, actually, that if there’s going to be an increase in anti-Semitism, we don’t want more anti-Semites coming to Germany.

It’s almost impossible not to have a dark laugh about this, at the sight of Germany, which to my mind has partly been doing this in order to absolve itself from its ongoing guilt for its behavior in the twentieth century, and is in the process arguably bringing back things which we had hoped we would not see again in Europe. I’m speaking about things like the fact that in places like Sweden there is a “walk a Jew to synagogue day,” walk a Jewish neighbor to synagogue so they’re not attacked. This sort of thing we had not imagined in our worst nightmares, but people should have expected at a very minimum that people, when they walk into a country, do not necessarily just immediately absorb the air and traditions and thoughts of that country.

This is obviously concerning both due to the nature of the problem itself and the rise of identity politics in response. Here in North America identity politics are a bit different, since Canada has never been a homogenous country, but that’s different in Europe. There is, for example, a distinct Dutch culture, so if you say, “the Netherlands for the Dutch” or “Britain for the British,” these statements start to ring a lot truer than from genuinely immigrant nations like Canada or the United States. How is that taking shape in Europe?

Well, this is a very interesting point you raise, because I mention Canada, America, and Australia in the book. It’s not enough, to my mind, to simply look at what is happening, or why it is happening. And these countries, including your own, suffer from some of the very thought diseases that now have been wracking Europe. The lead one of these is the idea that we are particularly guilty nations. That we are nations that as a result almost don’t have a right to some kind of an identity. Now, you’re right that it is different there than it is in Europe. In Britain, we have never really been a country of immigration, until the last half of the twentieth century. We were a very homogenous society, for better or worse, for at least a millennium, and for some time before that.

Of course, Canada and the United States can be described as nations of immigration, but here we land at one of the big questions which hangs over us all: Does the fact that the country is or has been or has become a country of immigration mean that the people in that country cannot voice concern when they feel that the country they appreciate and like is to their mind and to their eyes under some kind of risk? Is there, as it were, any warning siren that we can give off? What is the early warning siren that we can sound? I just got back from the West Coast of America, and I hear this a lot, you know: We’ve always been a nation of immigrants. Sure. But that does not mean that mass immigration or a borderless world is desirable now or will be in the future.

What we see in emerging in Canada and other places is a new secular religion where the treatment of indigenous peoples is the original sin, and then a constant discussion of those wrongdoings acts as penance and self-flagellation. You talk a lot about cultural confidence in your book, and how a lack of cultural confidence has led to rootlessness. Can you explain what you mean by that?

One of the things I’m concerned about with these deep themes that I tackle in different chapters in this book is that it is only European societies and societies that have derived from European society that suffer from this unbelievable self-flagellation. It comes, like many things, from a good place. Who wouldn’t want to be self-critical? Who would want to be accused of being blinkered? But the point is that most societies don’t join us in this. China is not wracked by self-flagellation. Turkey has never been asked to pay for the incredible sins of the Ottoman Empire. We never hear people demanding that a modern-day Turk in the 1990s should pay for the Armenian Genocide. So I’m not concerned with the fact that we do it so much as the fact that we are the only people who do it.

Then we have to wonder whether or not this obsession with our own wrongdoing is itself being used against us. That our own self-criticism and self-inquiry gets used against us [is] I think something that is overwhelmingly clear now in what you describe as the identity politics in North America. But young people in particular are getting this idea that these countries that they know and that they have benefitted from themselves are so uniquely guilty that they barely need to continue. It’s what I describe as a form of parochial internationalism. Because after all, you can’t have traveled anywhere else in the world if you think that Canada is a terrible, bigoted society. You can’t have gone anywhere if you think that Great Britain is a racist society. But this is what you do hear now in a new generation of people who have been brought up with this constant combination of self-flagellation and ignorance.

One of the things you’ve highlighted is that the pre-existing problems in Europe were exacerbated by the 2015 crisis, that it put so much pressure on the existing problems that people were forced to look them in the face. There’s a lot of discussion about European culture dying, and some blame the influx of migrants for that. But the birthrate collapsed voluntarily in most European cultures—most people stopped having kids because they didn’t want anymore kids. They gave up their religious heritage because they didn’t feel like going to church anymore. So in many ways it seems as if we’re seeing not just the strange death of Europe, but the strange suicide of Europe.

Well it’s funny you should say that, because the German translation of this book has a title that translates to The Strange Suicide of Europe, rather than the title in English, The Strange Death of Europe. But yes, it is to a very great extent self-imposed. But there’s a bit of good news in that things that are self-imposed, you yourself can get out of. There are two things here: The people coming in, and the questions that are raised, the good things that they bring, and the negative things that they bring. But there’s also the question of us. And of the two, the second one is in some ways easier to address.

In the question of us, I look at this question of why people in Europe may not be having children, and this is a very, very delicate subject for all sorts of reasons that we all know. One of the explanations given by German politicians after 2015 and by British politicians for a generation now is that the reason we need mass immigration—and we are talking here about levels of immigration that are historically unprecedented—that these levels of immigration are needed because we are an aging population and are no longer having children. This is wrong for so many reasons, but one of them, as I show in the book, is that if you look at opinion surveys and social attitude surveys, during the period that this is the case, most British women for instance want to have the number of children you would have if you had a replacement birthrate level. So the question is not how do we bring people in to be the next generation of people in our country but why is it that people in this country are not having the lives and producing the lives that they want to produce and have?

I think there is a whole set of reasons for that, some of which has to do with very straight-forward economics and some of which has to do with a form of cultural pessimism which has been forced upon them. If Germany needs to have more Germans in order to [support] this graying population, why not allow the German people to produce those Germans and encourage them to do so and look at ways to do so long before you decide that the next generation of Germans should be from Eritrea?

Now we see a generation of people, often my age and younger, who are saying that they really missed something, that they lost out on not being introduced to British culture, to Dutch culture, to German culture—and asking how we get that back. And these are questions that have right answers as well as a lot of wrong answers. So what would be your solution to this problem of rootlessness?

That is such an important point to make, because as I say in the book, although I don’t believe that Europeans are native racists or anything like that any more than I believe that of the average Canadian or the average American, I do think that if you don’t deal with these very serious societal challenges, you leave the terrain open for potentially very bad people down the road. You never want bad people to have good points. And I don’t believe this cultural deracination you referred to is endless. As you say, I think that there is a response to it, I think there is a backlash to it, and I think that it’s absolutely understandable and should be encouraged. People have a right to be shown and introduced to the culture that they were lucky enough to be born into.

After all, we are lucky. Canadians are very lucky people. British people are very lucky people. In the great lottery of life, we did not pull out a bad number here. So the question is how can we be allowed to continue in that culture in a recognizable way without being some kind of bigoted exclusionary people. Now, there are all sorts of things. The first thing is you have to slow the migration down. The second thing, after that, is that the people who have come to Europe or have been here for awhile be shown what we have, and be encouraged to be a part of it. Now, there are some people who would be racially exclusionary about that. I think that’s a despicable way of doing things because it’s not about race. Fundamentally, it’s about values. I think if you can say look, these are our values, and if you are here from all sorts of places around the world, we would encourage you to join in these values and to recognize them.

But there is a flipside to that. The flipside is that to be able to say you know what, if you don’t like these values, if you hate this society, if you think it’s the worst thing on the planet, then go somewhere else, because we can’t keep you here and allow you to just endlessly war against that society if you hate it that much. There has to be some kind of exclusionary part to make the inclusion bit work. And that, for our societies, is one of the great challenges of the years ahead: Not just how we can include people, but by the fact that inclusion requires exclusion. What are the limits to what we put up with? What are the points to which we say, you know what—maybe this isn’t the place for you.

I remember when I interviewed Mark Steyn on one of his books, I mentioned to him during a discussion on Islamic immigration that I was surprised by Ayaan Hirsi Ali’s suggestion that Christians needed to a better job of proselytizing Muslim immigrants. He cracked up and pointed out that the only reason I was surprised is because an atheist sounds like a more muscular Christian than the archbishop of Canterbury. Peter Hitchens’ advice to young people, as you know, is to emigrate. He talks about a lot of the same problems that you do, but his solution is utter pessimism. So especially for conservative-minded people, it’s hard not to get caught up in this pessimism. How do we look at an analysis of these problems and come to the conclusion that there is hope for the future?

It starts from realizing that central fact of how lucky we are at what we have. In the famous dictum of Edmund Burke, society and civilization are not just about what we are doing now, but a pact between the dead, the living, and those yet to be born. In that situation, you don’t have the right to decide that you’re just going to hand over to the next generation something like a large version of Mogadishu. You don’t have the right to do that because you were lucky enough to have been born into a place that was very different yourself and at the very least you pass on something that is recognizable, and if possible something that is better. I think there is no reason at all why people can’t join in that enterprise and be involved in that, but it starts from that realization. It starts from that realization that it is extraordinary luck that we have here.

I’m often asked about my attitude toward patriotism and nationalism and so on, and I always say that my own view of all of this is that these are slightly wrong interpretations of the question and that really one’s attitude towards one’s culture should be in terms of gratitude. Gratitude for what we have, and therefore a desire to pass it on. In order to be energized in that, there’s nothing clearer than looking around at the other options. I say this in the book at one point—why is it that so many people when they reach out for meaning do not find it in the historic traditions and the historic religion of their society, but—this has been documented in the UK—are attracted to Islam? Only for one reason: they don’t find in Christianity a belief system that seems very confident in its own beliefs. So why would you join it? It’s like buying a car [when the] owner says she’s not sure it works any longer.

So the question is what can we do to make sure that when people reach out for meaning, they reach out for the better forms of meaning, at the very least? I give the example of Islam, but obviously for Europe Islam is proving to be the hardest bit of the multicultural melting pot to swallow. It is finding it very hard, and not, I think, because it’s our own fault. It is Islam at the moment, but it could be almost anything. Mark Steyn has made this point as well: Almost anything that is culturally confident at this stage could step into this vacuum, and therefore anyone concerned about passing on the traditions and the freedoms and the liberties that we have should be concerned to address these fundamental principles and these fundamental questions.

Douglas, thank you so much for taking the time.

It was a great pleasure.

___________________________________________________________

For anyone interested, my book on The Culture War, which analyzes the journey our culture has taken from the way it was to the way it is and examines the Sexual Revolution, hook-up culture, the rise of the porn plague, abortion, commodity culture, euthanasia, and the gay rights movement, is available for sale here.

I agree with you. Douglas Murray is stellar. He is brilliant, clear, objective, avoids ad hominem attacks, reasonable and logical. A singular, clarion voice above the din that one typically must listen to on this topic. I have his book on Europe and I love it.