Blog Post

The murdered Jews of Austria

By Jonathon Van Maren

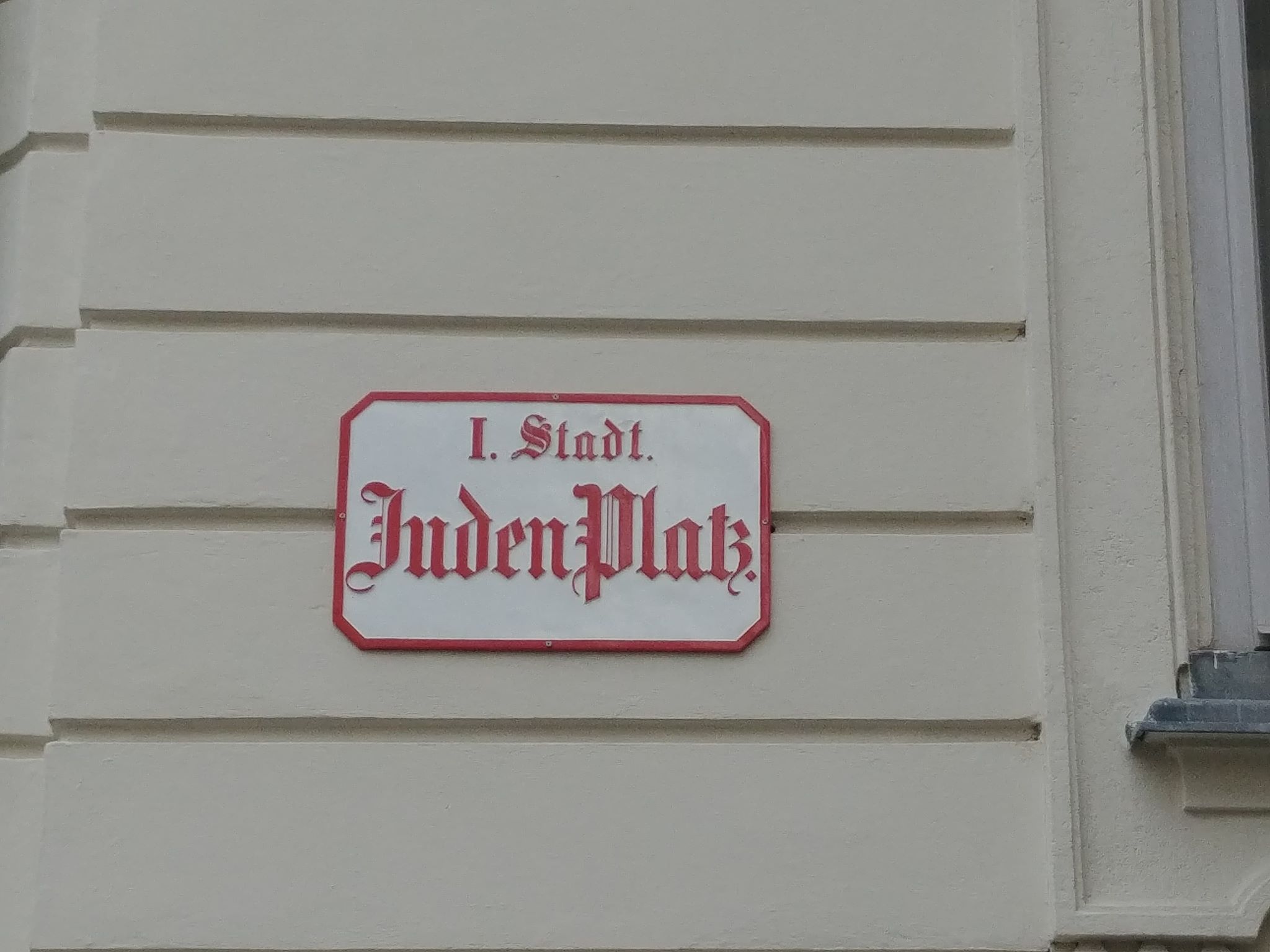

It was grey and chilly when I finally found the Judenplatz, a small cobblestoned square surrounded by cafes with the Jewish museum looming on one side. In the centre of the square, a memorial of steel and concrete rose out of the cobblestones to the height of nearly four metres, a strange box ribbed with deep grooves from bottom to top and a set of forbidding sealed doors embedded in the side. It is Vienna’s most prominent Holocaust memorial, and the grooves represent library shelves inside out with the books facing inwards, their titles unknown. It is a monument to the murdered People of the Book, and a plaque in front of the memorial tersely tells the story: “In commemoration of more than 65,000 Austrian Jews who were killed by the Nazis between 1938 and 1945.”

You can find Holocaust memorials in most European cities—some of them are viscerally powerful, while others are simply ugly and confusing. I remember stumbling across one of them, in the Bebelplatz in Berlin, entirely by accident. It is a clear window embedded into the cobblestones where on May 10, 1933, 20,000 books were burned by the Nazis. Joseph Goebbels gave a fiery speech, and his eager young wolves hurled armloads of books onto the blazing pyre. Today, if you peer through the glass, you can see rows and rows of empty bookshelves, enough to contain all the volumes that were incinerated in the early days of the Nazi regime, before they began to shove Jews into the flames, as well. A plaque nearby displays a quote by Heinrich Heine from his 1821 play Almansor: “That was only a prelude; where they burn books, they will in the end also burn people.”

I found this subterranean graveyard library far more compelling then Berlin’s Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, which is a bewildering, 19,000-square-metre maze of grey concrete slabs, organized in rows at varying heights. When I wandered through it, I couldn’t tell what it was supposed to mean, and looking into it later, I discovered that this was intentional. The architect, Peter Eisenman, stated that the Memorial was simply supposed to make people uneasy as they attempted to make sense of a system that was supposed to be orderly, but seemed to have “lost touch with human reason.” There was no symbolic significance to the design he had chosen, Eisenman said. The Memorial, like the Holocaust, should overwhelm people, and deny them the ability to try and make sense of something so monumentally evil.

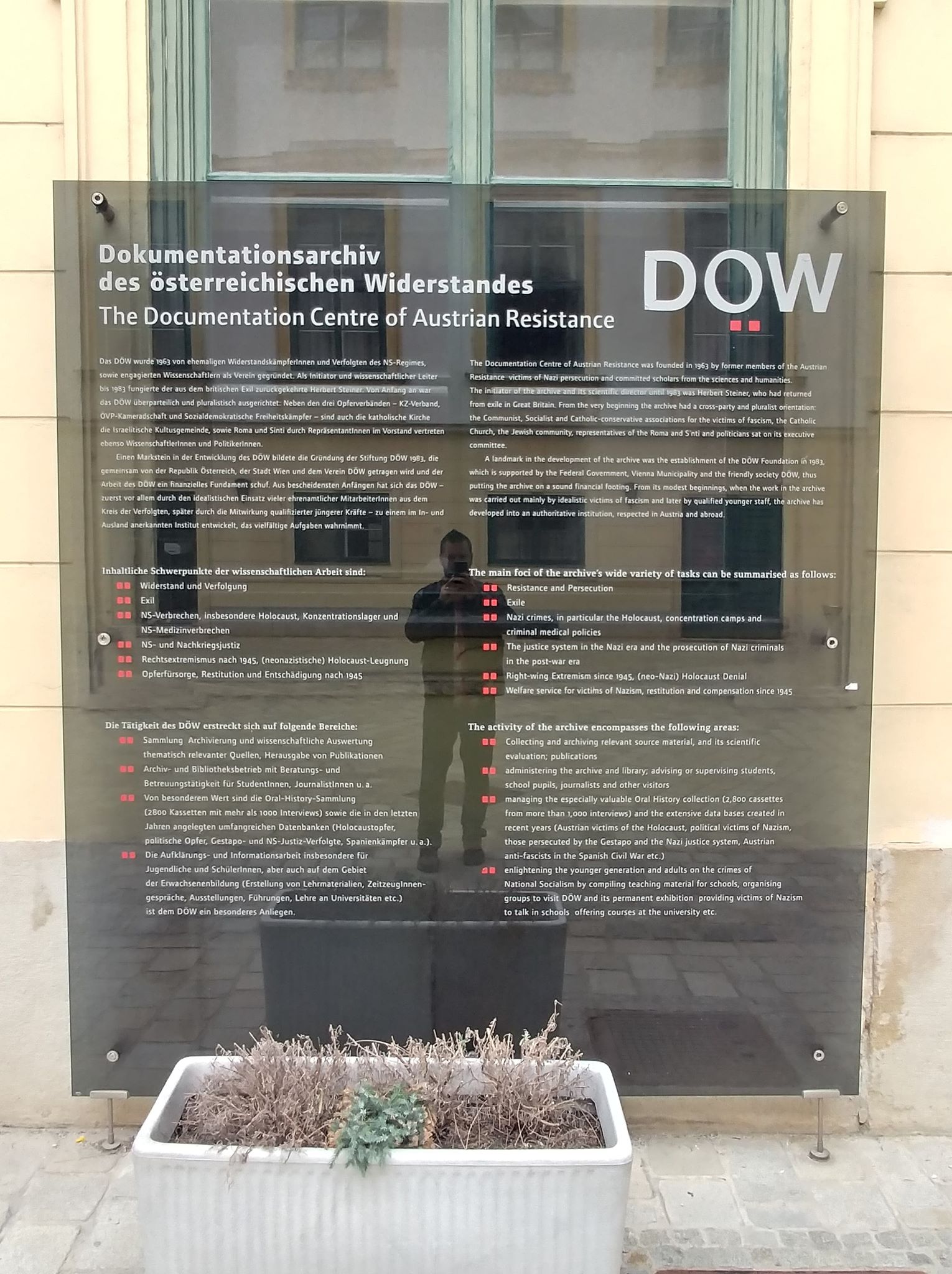

Holocaust memory is a complicated thing, especially in Europe. It took me awhile, but after about an hour of walking I tracked down the Documentation Centre of Austrian Resistance, a massive archive tucked into a little courtyard off a side street a short walk from the Judenplatz. Founded in 1963 by former members of the Austrian resistance, victims of Nazi persecution, and a number of scholars, the Centre was controversial in its early days—many Austrians did not want to talk about what had transpired during those years, and many of them did not look particularly kindly on members of the resistance. Despite initial hostility, the Centre has collected an enormous Oral History collection containing more than 2,800 tapes of over 1,000 interviews and databases attempting to track the victims of the Nazi regime, especially those who perished in the Holocaust.

A large exhibit was on display when I arrived, filled with large informational plaques, photographs, and artifacts detailing Austria’s journey from Anschluss to the war’s aftermath. Over 1,300 executions were carried out by guillotine here in Vienna, most of them resistance workers, and photograph after photograph revealed the violence that had paralyzed the nation’s capital. On October 8, 1938, for example, the Viennese Hitler Youth took revenge for an anti-Nazi demonstration carried out by Catholic youth in front of St. Stephen’s Cathedral by storming the archbishop’s palace and throwing a priest out of the window. In fact, the only nun to be executed in Austria was also killed in Vienna—Sister Restituta (Helene Kafka), was murdered for opposing Nazi orders in her role as a nurse in Modling and distributing anti-Nazi poems. She was canonized by Pope John Paul II in 1998.

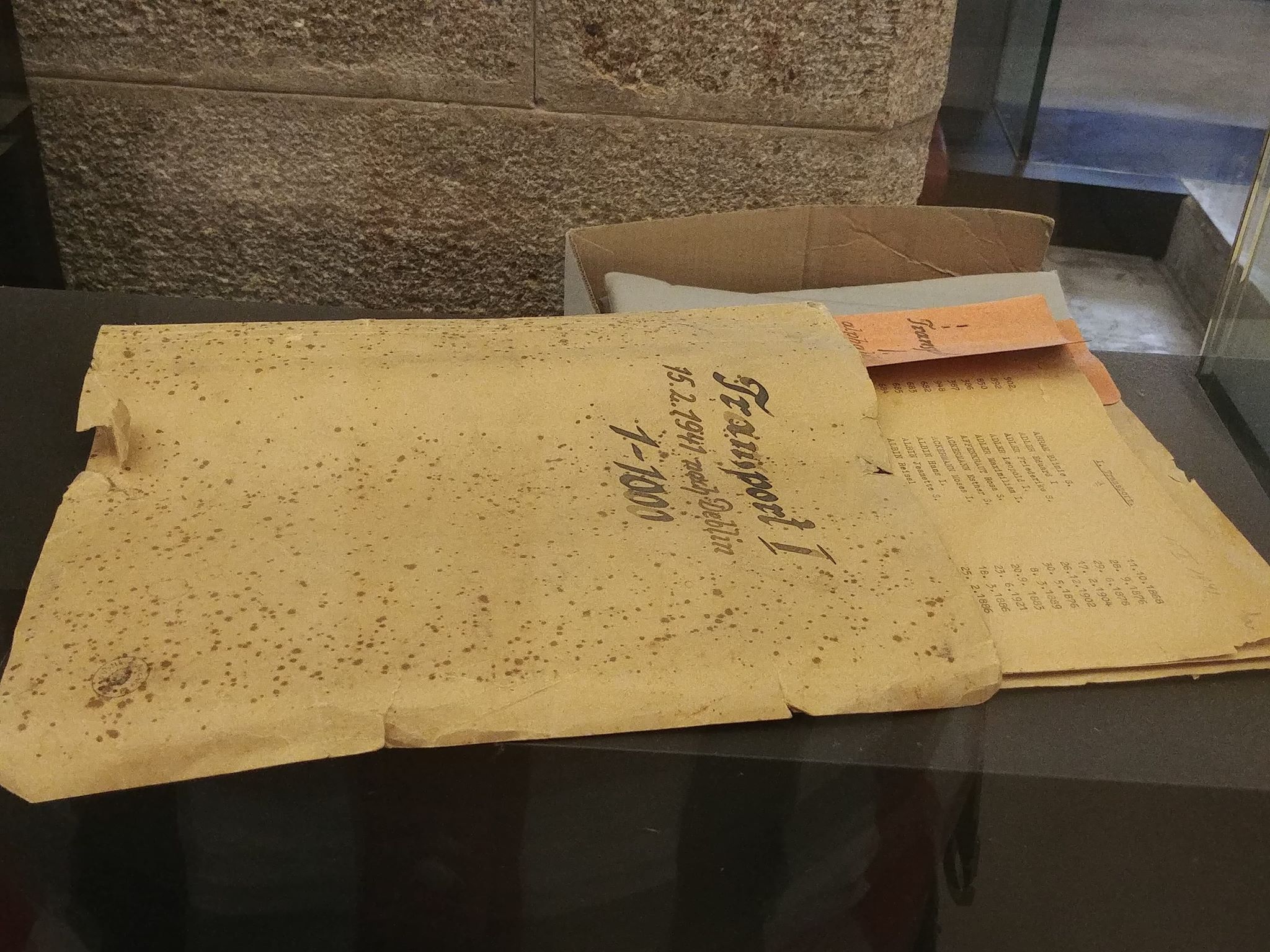

It was the near-total destruction of the Austrian Jews that dominated much of the exhibit. At the outbreak of World War II, there were 70,000 Jews in Austria. The first deportations began already in October of 1939, with many being shipped to Poland and a network of ghettos. Towards the end of 1941, many of the deportees did not even make it that far, but were instead shot almost immediately after they were herded off the trains. Others were shipped to Theresiendstadt, a notorious extermination camp. By October of 1942, only 8,000 Jews were left, most of them partners in mixed marriages. The exhibit displayed deportation lists and revealed the grim statistics. Deportation List No. 11 from Vienna to Kowno on November 23, 1941 listed the names of 1,000 people. None of them survived. Deportation List No. 12 also contained 1,000 names. Only three survived. One of the original lists lay in a glass case, a copy of Deportation List No. 1 from Vienna to Opole on February 15, 1941. Of 1,002 deportees, 28 survived. The list peeked out of a stained yellow envelope, and I could make out the first few names: Abram, Blimie; Adler, Eduard I; Adler, Leopold I…

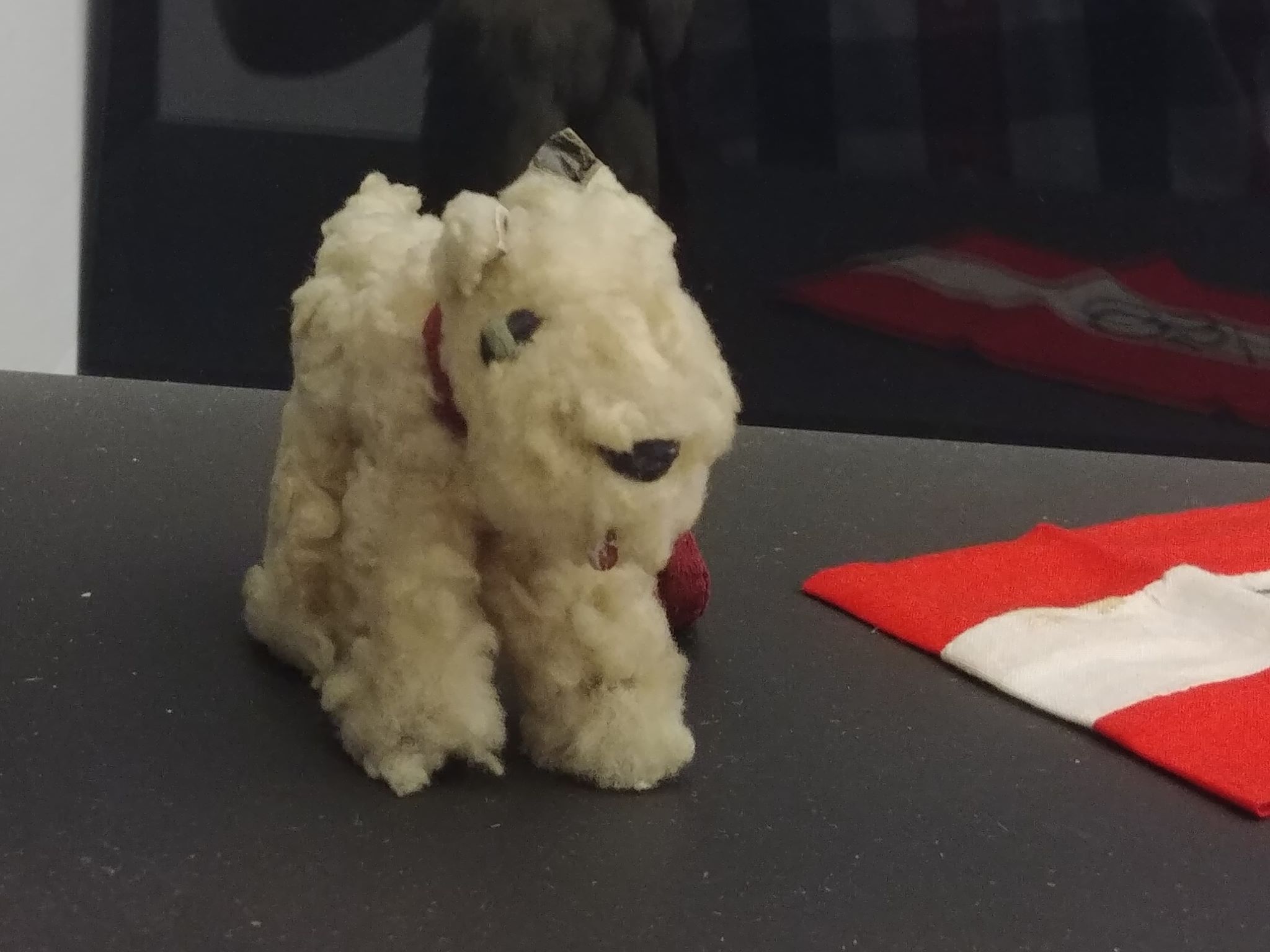

In one display case, a faded yellow Star of David with the word JUDE stitched into the centre lay next to other artifacts, including a tiny plush dog that was made by the female inmates of Ravensbruck as a present for children who were also imprisoned in the camp. It was a little gift for the Christmas of 1942. There was also prisoner’s uniforms, baggy white and blue-striped clothing that looked like ill-fitting pajamas. Nearby was a green satchel, with a label revealing it to be a “partisan’s fighter’s bag belonging to Janez Wutte-Luc, partisan fighter along the northern part of the Drava.” These were combined with the black-and-white photographs of Vienna festooned with swastikas, one of them showing Adolf Eichmann chatting with a cluster of men in trench coats, twenty-four years before he would be hanged for his crimes against the Jews in a nation formed by the survivors of the Final Solution he was then beginning to implement.

After the war ended, the reckoning began in earnest, with the Allied occupation, denazification, and the People’s Courts set up to punish those who had committed Nazi crimes. The Austrian government was cooperative, but only in order to get the Allies out of their country as soon as possible. Rooting out the Nazis and forcing those who had assisted the regime to face consequences for their actions was something the Austrians were profoundly disinterested in—the government simply wanted to forget about the Nazi era, and quietly offer the average Nazi a swift way to reintegrate. In fact, the Conservative OVP and the Socialist SPO were calling for a relaxation of denazification regulations and an end to prosecutions in 1947, a mere two years after the end of the war. An amnesty was declared in 1949, with many ex-Nazis getting their voting rights back. In fact, the Austrian government attempted to abolish the People’s Courts entirely, but the Allies blocked the effort.

Almost immediately after the Allies left in 1955, the Austrian Parliament wrapped up the People’s Courts, and a general amnesty followed two short years later in 1957. By the mid-1960s, it was only possible to prosecute those who had directly participated in murders. Austria wanted to move on, and publicly, the official position was that Austria had been Hitler’s first victim rather than a participant in the Holocaust and accompanying crimes against humanity. It was not until 1985 that the war record of Kurt Waldheim, who successfully ran for president in 1986, triggered an international conversation on Austria’s role in the Second World War. And it took until 1991 for Federal Chancellor Franz Vranitzky to come forward and confess that Austria had not simply been a helpless victim, but shared the responsibility for many of Nazi Germany’s crimes.

Almost all of the men and women who actually participated in the crimes of the Third Reich are now gone, and in 2014 the Simon Wiesenthal Center launched Operation Last Chance, their final attempt to bring elderly war criminals to justice. I spoke with top Nazi hunter Dr. Efraim Zuroff at the time, and he told me that there were still a handful of men they were seeking to bring to justice—if only to once again see the crimes of the Holocaust exposed in open court, where those who seek to ignore or downplay the Shoah would be once again forced to reckon with the inferno that had reduced six million people to ash. As memory slowly fades into history and the men and the monsters who forced the Jews to scrub the cobblestones of Vienna before sending them to their doom descend one by one into the grave, all we have left is black and white photographs of the horrors that once played out across Europe—and concrete memorials that remind us to never, ever forget.

n Va

n Va