Blog Post

The Second World War: Saving Christian civilization from Hitler’s Reich

By Jonathon Van Maren

My introduction to this series on the 20th century, “The Century that Changed Everything,” can be found here. Part I is “The World Before the War”. Part II, “How the Great War transformed Western civilization–and is still with us today,” can be found here. This column on the Second World War is the fourth installment in the series.

It was a beautiful green spring day in Vancouver, and I was chatting with a supporter of the pro-life organization I work for. Sissy von Dehn, who is in her eighties, was telling me that she’d enjoyed a recent column I wrote, and almost offhandedly mentioned that her father had been a journalist. Robert Wendelin Keyserlingk, in fact, had been nearly everywhere: As a child, his family had fled the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia, he’d lived in China for awhile, traveled back and forth across the Atlantic, and became a freelancer in Vancouver. Back on the Continent, he landed a job as a rewrite editor for the United Press in Germany in October of 1930, where he covered the pitched battles between the Nazis and the Communists on the streets and in the bars of Berlin—a body count of half a dozen was apparently not unusual.

In fact, Sissy told me, her father’s career had introduced him to some strange people. “He even interviewed Hitler,” she told me. I gaped. “Hitler?”

“Yes. He wrote my mother letters about it at the time. Would you like to read them?”

This is the sort of thing every history buff dreams of: The chance to read a genuinely important eyewitness account with the potential of shedding new light on an old subject. I will admit to being giddy when Sissy made me copies of the letters and allowed me to keep them.

The background to the story of the Hitler interview is almost as fascinating as the encounter itself. Keyserlingk—Sissy’s father—discovered through his contacts on July 11, 1931, that a special meeting of the executive of the Bank of International Settlement would be held at Basle, Switzerland, to discuss commercial debt and the ongoing economic crisis in Germany. The luminaries attending the meeting, however, were concerned: The Nazis had secured 107 seats in the Reichstag in the previous year’s elections, and they still did not know what the Nazi position on commercial debt was. It was difficult to know precisely what to do when Hitler was a wild card.

Keyserlingk sensed an opportunity. If he could secure an interview with Hitler to coincide with the meeting of the Bank of International Settlement, it would be a real scoop. The problem was that Goering, Hitler’s political representative in Berlin, jealously guarded access to the Fuehrer and demanded that all requests go through him. Keyserlingk decided to attempt an end run around Goering by asking several of his banker friends to appoint him their private representative and ask Hitler some questions they were eager to have answers to. Then he would tell Hitler that in view of the upcoming meeting in Basle, the United Press wanted to publish the answers.

He first attempted direct contact Saturday night, picking up the telephone and informing the operator that he wanted to place a long-distance call from Berlin to “Adolf Hitler—Brown House, Munich, for Count Keyserlingk.” (His family still retained some aristocratic titles, which provided more gravitas than the ID of a newspaperman.) The girl came back on the line soon—Hitler wasn’t available. Hess, then? Rudolf Hess came on momentarily and asked which Count Keyserlingk he was speaking to. Robert Wendelin Keyserlingk, speaking for financial interests that, due to the upcoming meeting the following Tuesday, made it imperative that he speak with Hitler.

Hess called back at midnight. “I have just spoken to the Fuehrer on the telephone and he tells me that he would be able to see you not earlier than Tuesday.” Not good enough, this is urgent. Get me a meeting Monday to settle these matters. Hess hung up, and called back at 2:30 AM. Hitler would see him at 5 PM on Monday, July 13.

In the sheaf of letters Sissy gave me, I found a note from Keyserlingk to his fiancée back in England—the Baroness von der Recke, who he affectionately called “Sigu”—from Monday, a few quick lines to let her know that “All went well and I got a big story from the man himself…Lots of love and best regards from Munich.” A few days later, he sent her a long letter describing his encounter—how he’d gotten the United Press to sign off on the idea, how he’d gotten the Nazis to agree to the interview, and then, his arrival at the Nazi headquarters in Munich, the “Braunes Haus”:

Outside the rather large building was gathered a crowd of youths, real “Rotzanasen” the type of messenger-boys and small shop-keeper’s assistants who were waiting for the “Chief” to make an appearance. On giving my name I was immediately admitted by a man in SA uniform. In the hall were innumerable young people who looked like a mixture between “Wandervogel” Boy scouts and “Gesundbeter”. I was staggered by the shoddiness of the entourage and the childishness of the everlasting salutes and clicking of heels. All looked so unreal and silly. This was supposed to be the place from which the salvation of Germany was to emanate.

I was brought to a waiting room and there met the secretary of the leader—Rudolf Hess. Hess was a nice young chap who looked like a fanatic, very earnest and eager but who was not overburdened by any too much intelligence. He started in a very unintelligent way to put questions to me and to try and sound me out, I did not find any difficulty of getting him where I wanted. He began by telling me that the “Fuhrer” was very busy and might not be able to see me. I told him that I did not come to hear that but that I absolutely insisted and that I was going to see him without any delay before my train left at 8:30 pm. Finally he came back, after having inquired, and asked me to return at about 7. I was dead tired and immediately went to the hotel. There I took a bath and rested for awhile.

Just as I was beginning to have supper the telephone went and I was called to come. This time I only waited two minutes and was then ushered into the august presence of Hitler himself. Imagine my disgust when I saw the idol of millions, the man that people of our set are willing to follow blindly and for whom they sacrifice intelligence, good manners and often decency. Hitler reminds me of a small post-office clerk who suddenly finds himself in a position far above his real rank and feels thoroughly beyond his depth. I frankly admit that I had felt a little nervous at first and was quite prepared to be awed and overcome by the personality of this tribune of the people by his personal magnetism, charm, or whatever you like.

But nothing of the sort. On one side of the mahogany desk sat Hess, on the other the economic adviser Dr. Otto Wagener and in front of me Adolf himself. Quite frankly I felt in bad society, I felt as though I had suddenly sat down with people at a dinner who might eat the peas with their knife and spit on the floor. But what was worse, I felt that not one of those men was a leader but just small average intelligetnzia, very small and almost below average. Well, I very soon regained my self-control and the fight started. At first he did not know what to do. He was thoroughly scared of events, of me, of everybody and really made quite a pitiful impression of helplessness. He realized that the day was at hand where he would have to make good his promise. The German people were in a desperate plight and many looked to him for leadership. At the same time the man who had on so many occasions talked to the multitude in such loud words of courage, leadership and nerves was sitting before me a harassed and frightened individual who made the verse of “Gothe’s Zauberlehrling” come to mind. He had conjured the spirits and they came but he did not know how to get rid of them again.

I asked for a statement and he answered that he was afraid to do anything for fear of aggravating the situation. A wonderful man: I am sending you the clipping of the interview as it appeared in abbreviated form in the Paris edition of the Herald Tribune. Finally I got the promise from him that he would give me a signed statement because we were afraid that he might otherwise if his friends should object to what he said, dementi everything. After about half an hour with him I returned to my hotel and waited for his secretary to bring me the statement. He finally arrived and I immediately telephoned it through to Berlin. Then I asked the secretary to remain and work over the rest of the story with me as I did not want to say anything that was not absolutely according to fact.

Keyserlingk’s big scoop almost got derailed after the fact, as Goering soon caught wind of it and called him up in a rage, infuriated by the interview, the questions, and Hitler’s having signed off on the whole thing. But the story ran nonetheless, despite Nazi threats to deny the entire story. Seventeen years later, Keyserlingk wrote in his memoir that he’d often wished his fiancée—whom he married on December 1, 1931—hadn’t kept his letters, which in hindsight had dramatically underestimated the Nazi threat: “I certainly failed to appraise the potentialities of Hitler and his movement and frequently, if I would exert my authority as paterfamilias too autodidactically I was teased about the ‘infallibility’ of my judgement.”

But like Keyserlingk and everyone else, we now look back on the period of the Nazi rise through the inescapable lens of The War.

***

Like most kids my age, I grew up hearing stories about the Second World War. For my family—on both my maternal and paternal sides—“the War” meant the German occupation of the Netherlands, and over cups of coffee my grandparents would frequently drop anecdotes or details we hadn’t heard before. One Saturday evening years ago, my maternal grandmother began reminiscing about the Nazi bombing of Rotterdam, where she had lived with her family. They hid for several days in the cellar, and she recalled the buildings heaving and shuddering overhead. One account noted that the heat from the bombardment was so severe that cherry trees budded, blossomed, and blackened in mere minutes. When they emerged, the rubble was still burning. An elder from their church, my Oma recalled, had pulled his 18-year-old daughter from the ruins and gently laid her body on a vegetable cart.

Not so long ago, “the War” still felt recent. The sinister Goebbels, the corpulent Goering, and the Lucifer of the 20th century Hitler himself frequently played starring roles in childhood games (always falling victim to extremely successful assassination attempts.) But when my own children arrived, I realized that it is very unlikely that they will ever hear the stories about that period first-hand. To them, the Second World War will feel like the First World War did to me growing up—an event rendered hazy by the fog of time. (My great-grandfather Gijsbert Van Maren was in the Dutch army during the Great War, but the Netherlands successfully remained neutral and avoided any fighting.)

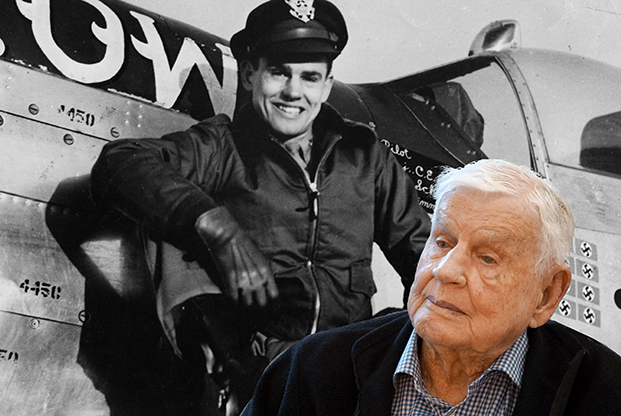

But for now, there are still aged men and women who, when they were young and strong, fought the three-headed Axis beast to a standstill and lived to tell the tale. One is 98-year-old Bud Anderson, a veteran of World War II, Korea, and Vietnam—a triple ace with the best flying score in his P-51 Mustang squadron. In his gravelly, far-off voice, he told me that every American veteran remembers where they were when Pearl Harbor was attacked on December 7, 1941. Anderson, a California boy, was working as a junior aircraft mechanic at an air depot near Sacramento, and the foreman showed up to tell them. “That’s when I knew we were off to war. I didn’t even know where Pearl Harbor was.”

Anderson enlisted with the United States Army as an aviation cadet, received his wings and commission as a second lieutenant in September, and ended up based in RAF Leiston, England, flying combat tours against the Luftwaffe with the 363rd Fighter Squadron of the 357th Fighter Group. “We had good pilots in our group,” he told me proudly. “All we had to do was be turned loose and we were going to chew somebody up. I was quite proud of our unit. That was one of the greatest times of my life, working with these guys.” When I asked him what it was like to fight the German pilots over Europe, his response was to the point: “It was very rewarding. It was scary when you first got over there, before you got any kind of experience. You looked down, and that’s enemy territory. If I go down, all these farmers are going to pitchfork me, they’re just waitin’. Once I got some experience and was successful, it kind of opened things up. I wanted to do it. You had to want to engage the enemy. There were a lot of fighter pilots that flew a whole tour and never saw an enemy airplane.”

That, however, was not Anderson’s experience. When I asked him about the first time he shot down a German fighter, he began chuckling. He’d been “casing ‘em,” he told me, and his squadron had been following “the 18,000-foot rule—you drive the enemy away and you come back. That was our instructions. I chased these guys down to 18,000 feet, fired a long burst, came on back. But on this particular mission, I was a leader and on my way home. You hadda fly with three, and another squadron pulled in behind us. We got about halfway out of Germany when here came three ME-109s. We were on the left side, and they were coming in from the right side. They obviously couldn’t see us, because there was seven of us. I thought: One of these is mine. So we cut ‘em off at the pass, before they could do any attacking. I latched onto this guy. It was down low, where an ME-109 could give the Mustang a harder time. I just couldn’t get on this guy’s tail. I was coming at him at very steep angles, and I just couldn’t slide in behind him.”

Anderson decided to gamble. “I had been through three gunnery schools, so I knew how to shoot. I said, when this guy comes around again—we’re both in a very high-speed turn—that means your wingtip is vertical—I’m going to get my stick site right on him, pull through him—this’ll mean I can’t see him, because he’ll be under my nose. I’m going to pull through to my estimated lead, fire a burst, and see what happens. Sure enough, I hit him with a golden bullet. He pulled up and bailed out.” John Anderson, another pilot, pulled up beside him. “He’s grinning like a kid, and he gave me the OK sign.” Anderson wondered whether John had shot the plane down rather than him—confirmation of a kill had to come from other members of the squadron.

Back on solid ground, he asked several members of the squadron whether they’d seen who made the kill, but all of them had been out of position and couldn’t confirm. He headed over to the club for a drink, and John ran over to him from the bar, beaming. “Andy,” he said, “that’s the greatest shot I ever saw. You got the sucker out there at about 60 degrees!” Anderson ran his fingers down up and down his left shoulder and shrugged it off: “Aw, Johnny, lucky shot.” And then, he told me with a laugh, “I rushed to the phone and claimed my first victory.”

Anderson doesn’t remember shooting down the plane that made him a war ace—he only realized it later, after he’d landed. To make war they way the did in the skies over Europe, he told me, you had to believe that the Nazis were evil. You needed to believe that because when you saw a plane diving towards the ground belching fire and smoke with no nearby mushroom to indicate a successful bailout, you had to consider it a job well done. Still, he said, “we were after the machine, not the pilot.”

That soon changed. In the spring of 1944, the pilots received new rules of engagement: “Pursue and destroy.” No longer was it enough to blow the Luftwaffe planes out of the air—the new orders were to follow them to the ground and make sure the pilot was dead, too. D-Day was coming, and high command wanted the Luftwaffe destroyed before the invasion. “So that’s what we did. I think it was remarkable,” Anderson told me. “We did it by killing their experienced pilots. That’s the story of how we defeated the Luftwaffe. I don’t think it’s very well-told in the history books. We tore into them when they came in. It also let us go out and look for them. We were hamstrung before because we had to stay with the bombers. But when they turned us loose, we could go looking for them and try to get them before they formed up. The kills really sky-rocketed from there. The Germans did not have a good pilot replacement program, and they just ran out of their core experienced pilots.” Anderson himself racked up 16 and a quarter kills, a few probable kills, and crippled some fighters over the course of 116 missions.

That soon changed. In the spring of 1944, the pilots received new rules of engagement: “Pursue and destroy.” No longer was it enough to blow the Luftwaffe planes out of the air—the new orders were to follow them to the ground and make sure the pilot was dead, too. D-Day was coming, and high command wanted the Luftwaffe destroyed before the invasion. “So that’s what we did. I think it was remarkable,” Anderson told me. “We did it by killing their experienced pilots. That’s the story of how we defeated the Luftwaffe. I don’t think it’s very well-told in the history books. We tore into them when they came in. It also let us go out and look for them. We were hamstrung before because we had to stay with the bombers. But when they turned us loose, we could go looking for them and try to get them before they formed up. The kills really sky-rocketed from there. The Germans did not have a good pilot replacement program, and they just ran out of their core experienced pilots.” Anderson himself racked up 16 and a quarter kills, a few probable kills, and crippled some fighters over the course of 116 missions.

Even now, all these years later, part of him still misses it all. “I enjoyed squadron life,” he told me. “I enjoyed being in a combat unit more than anything I did. The camaraderie. Most of us guys would say we were fighting for our country, or the flag. But we were fighting for each other. I think that’s true of any good combat unit with good morale. A guy gets wounded, and the first thing he wants to now is when can I leave to get back to my unit. That kind of a feeling. World War II was a big deal. The tragic thing is we lost so many human lives because of a war. As most history books will tell you, forty to fifty million people died. I can’t comprehend that. I try to break it down: How did it effect my unit? The guys I deployed overseas with? Well, the squadron had exactly 28 pilots, and 50% of them were either killed or made prisoner of war. That’s high casualties. We had a five to one kill ratio. For every one they shot down of us, we shot down five of them. The enormity of it…” And his voice trailed off.

Bud Anderson, like almost everyone else, lost friends. He later named his son after two of them, Jim Browning and Eddie Simpson. “Jim Browning came back for a second tour like I did, except he was later on. He and Captain Bochkay were out looking for trouble and they found it. Two ME-262s. One of them tried to do what they shouldn’t do: Dogfight with a Mustang. A Mustang will just eat ‘em up. Bochkay shot him down, and when he turned to look for Browning, Browning wasn’t there. Made radio calls. As it turned out, Jim had engaged the other 262 and they played chicken—and nobody broke. They had a violent mid-air collision. Vaporized them both. Jim had been in my flight from day one.”

Eddie Simpson has been Anderson’s wingman early on, and later became a flight leader. In 1944, he was shot down over France and bailed out. It would be several years before Simpson’s fate was pieced together. Once on the ground, Simpson connected with French resistance fighters, the maquis. While attending a funeral service for nine freedom fighters who had been killed by the Germans, a Nazi patrol opened fire on them, and the Free French forces loaded up a convoy of trucks to move to a new location. Simpson climbed on to the last truck in the convoy as it headed down the narrow forest trails leading to the Orleans highway. As they pulled onto the highway, a column of German armored cars spotted them. Realizing that the Germans had to be delayed or the convoy would be captured, Simpson and five of the maquis dropped from the truck with a heavy machine gun and opened fire, stopping the lead German vehicle and blocking the road. They continued firing until, one by one, they were killed—and the convoy was safe. On August 14, 1944, Simpson died to save men and women he did not know.

Paris was liberated that same month as the Red Army hammered through Eastern Europe towards Berlin, and by the end of the year, the German counter-offensive at the Battle of the Bulge—Hitler’s last big gamble—had killed 19,000 Americans but failed to halt the Allied advance. On April 30, 1945, Hitler put a pistol in his mouth in the Chancery bunker in Berlin and followed his millions of victims into eternity.

V-E Day, Anderson recalled, “was a big let-down.” He’d gone stateside in January, and was at a training base in Texas with his friend Chuck Yeager (the famous American test pilot who would, two years later, become the first in history to be confirmed exceeding the speed of sound in level flight.) They celebrated together, the two of them and their wives. “We went out somewhere in Texas.”

***

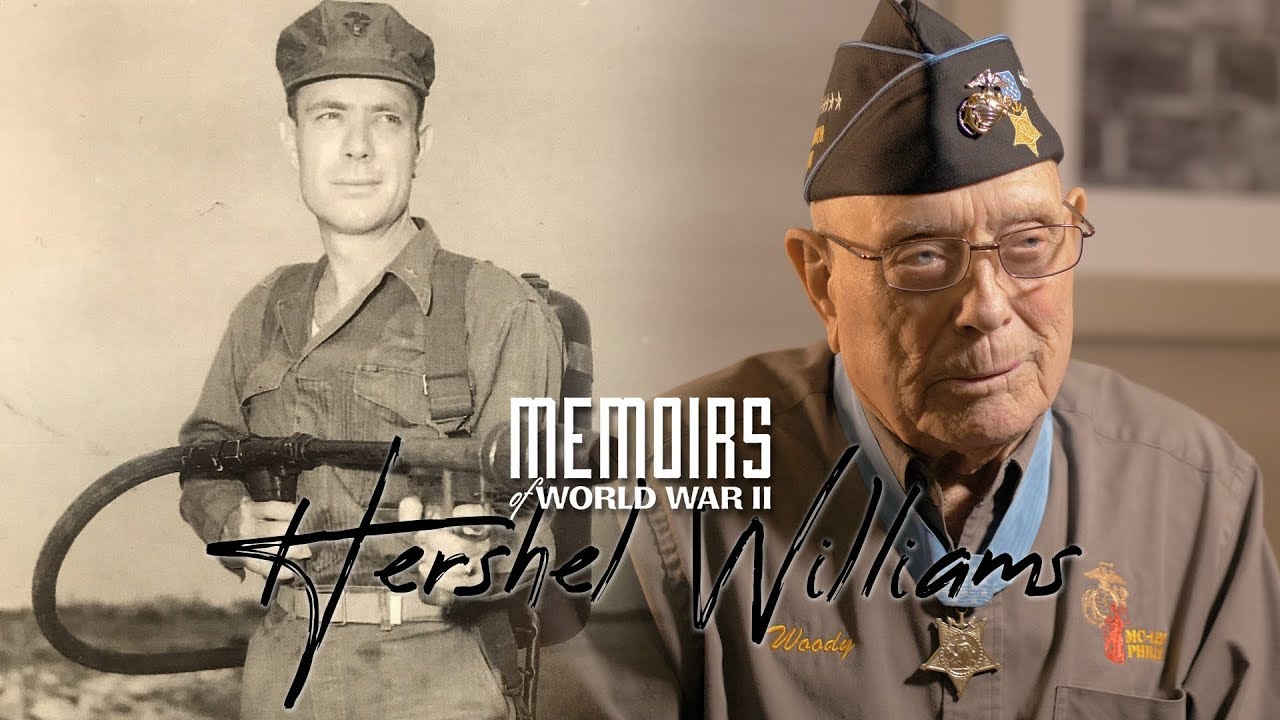

On the other side of the world, a very different war was being fought. To hear about the fight against the Japanese in the Pacific, I got in touch with 96-year-old Hershel “Woody” Williams, the last surviving Medal of Honor recipient from World War II.

Born and raised on a dairy farm in Quiet Dell, West Virginia during the Great Depression, Woody’s earliest memories involve milking by hand, delivering milk in glass quart or pint bottles, and the huge blocks of ice necessary to keep everything from spoiling. The family car was a Model A Ford (and then the very high-class Model T Ford), but by the time Woody was eleven, his father died of a heart attack and several siblings had died during a flu pandemic. Eventually, when Woody and his brothers were off in the military, his mother was forced to sell the farm.

Woody joined the Civilian Conservation Corps at age 16, in 1940 (as did his brothers), and it paid a whopping 21 dollars a month. Woody was in Whitehall, Montana with the CCC when Pearl Harbor got bombed, and although he tried to join the service right away, he needed parental consent as he was not yet 18. His mother refused to give it, and Woody was forced to wait. He was accepted into the Marine Corps in May 1943, and after training in California, he was sent to the Pacific. His brothers were in Europe.

Woody first landed at Guadalcanal, which the Americans had taken in 1942. “We stayed for six months, and then we shipped out to be support for the Second Marine Division—we were the Third—which was attacking Saipan,” he told me. “We were out in the ocean waiting in the event that they needed additional Marines. They didn’t.” It was on Guam in July that Woody first tasted combat. “When we hit the beach at Guam, it was probably one of the scariest moments of my time. We had to get off the boats out in the water, knee-high to waist high, because the boat hit the sandbar and we had to wade ashore. The Japanese were shooting at us and dropping mortars on us. Once we got ashore and we got some ground under us and we could start digging a foxhole or get behind something for some protection, we adjusted.”

When they left Guam for Iwo Jima, Woody and his fellow Marines had no idea where they were going until they were out on the ocean. “We had just gone 19 miles from coastline to coastline on Guam,” Woody told me, “and my squad, including me, couldn’t figure out why we would go take such a little place. It was only 2.4 miles by 5—it couldn’t be much of anything.” They were told they would be a reserve unit and would probably head back to Guam in a week or so without even getting off the ship. They had no intelligence on Iwo Jima and did not yet know that the island was crisscrossed by miles of tunnels and 22,000 waiting Japanese soldiers.

On February 19, 1945, when the first division hit the island, Woody was still out on the ocean. He and his comrades couldn’t see or hear anything beyond the occasional plane going by. Around midnight, the ship’s loudspeakers crackled to life, announcing that because of the number of men killed that first day, the relief troops would be off the ship before daylight. The men stuffed down chow at 3 AM, gathered their gear, and piled into the boats. After floating on the water all day, however, they were finally forced to turn back to the ship—the 4th and 5th Marine Divisions had not captured a large enough beachhead for a landing. After another 3 AM chowtime, the Marines were back on the boats. This time, they could land. Woody Williams landed with the First Battalion, 21st Marines on February 21, 1945.

It was a brutal, bloody fight. “On the 23rd, we were still fighting for the first airfield,” he told me. “They had pillboxes protecting the airfield. As we tried to advance, they had all of the advantage. They were inside of a concrete structure, we were out in the open, running from one position to another. We were a great target. We kept losing Marines very rapidly and could not break through those pillboxes. Every time we’d try, they’d kill another group of us and we had to retreat.” He laughed. “I’ve used a phrase many times in my life: We never withdraw, we never retreat, we just advance to the rear. So that’s what we did, we advanced to the rear. I had six Marines under me when we landed. We were all flame-thrower and demolition trained—we could either burn it or blow it up. My job as the person in charge of the unit was to make sure that the operators had whatever they needed to function whenever they were needed by command. By the 23rd, those Marines were gone. I’ve never known whether they were wounded or killed. But I was the last flame-thrower in C Company. That’s how I got the job of eliminating some of the pillboxes.”

It was a brutal, bloody fight. “On the 23rd, we were still fighting for the first airfield,” he told me. “They had pillboxes protecting the airfield. As we tried to advance, they had all of the advantage. They were inside of a concrete structure, we were out in the open, running from one position to another. We were a great target. We kept losing Marines very rapidly and could not break through those pillboxes. Every time we’d try, they’d kill another group of us and we had to retreat.” He laughed. “I’ve used a phrase many times in my life: We never withdraw, we never retreat, we just advance to the rear. So that’s what we did, we advanced to the rear. I had six Marines under me when we landed. We were all flame-thrower and demolition trained—we could either burn it or blow it up. My job as the person in charge of the unit was to make sure that the operators had whatever they needed to function whenever they were needed by command. By the 23rd, those Marines were gone. I’ve never known whether they were wounded or killed. But I was the last flame-thrower in C Company. That’s how I got the job of eliminating some of the pillboxes.”

What Williams did next would earn him one of the most prestigious military awards in the history of combat. Covered by four riflemen, he fought for four hours under nonstop enemy fire, constantly returning back to his lines to prepare more demolitions charges and fetch more flamethrowers. When I asked him about it, he sounded as if he were reciting a military report: “I was able to eliminate the enemy in seven of those pillboxes. We couldn’t do anything about the pillboxes; they were built so strong with some form of concrete that had metal rods in it. Artillery, bazookas—it didn’t do anything to them. They were fully protected. They had an aperture across the front of every pillbox that was about eight inches in height, and that’s where they could stick their rifles and machine guns out—and that was the only place we could hit.” To clear the pillboxes, Woody had to somehow get close enough to pour fire through the opening.

“Much of that day I do not remember,” he told me with a chuckle. “It’s one of those things I’ve lived with all my life, ever since I came back from the Marine Corps. How really did I do it? Why wasn’t I wounded or hit in some way with shrapnel or bullets or something in those four hours? They never touched me. But some of those pillboxes are absolutely not in my memory bank at all. I can remember a couple of ‘em vividly. But one of the things that has absolutely bugged me—still does—I’ve talked to a number of people and I haven’t been able to get a good, solid answer: How did I get those other five flamethrowers? I remember the first one very well. Taking off, those four Marines who were assigned to me, and I remember placing them where they could shoot at the pillbox I was going to broach. But how I got the additional flamethrowers is one of those things that has never been in my memory bank.”

What Woody does remember is extraordinary. “With 70 pounds on your back, you don’t get up and walk around very much. Particularly in danger, you crawl on the ground to make yourself as a little a target as you possibly can. I was crawling towards that pillbox in a ditch that the Japanese had dug to enable them to go from one pillbox to another without getting above ground. I was in their ditch, and they were shooting at me with a Nambu machine gun. I remember the bullets ricocheting off the back of my flamethrower. I saw smoke coming out of the top of the pillbox, so when they were reloading their machine gun or had run out of bullets, I jumped up and ran to the side to get out of their line of fire. That’s when I decided I’d go up on top of the pillbox to see where the smoke was coming from, because if there was a hole up there I could put flame down through it. That one I remember very well.”

Woody had to get quite close to the pillboxes for his weapons to be effective—less than twenty yards, or the flame would disperse and fan out into a huge ball of flame. “If I shot it in the air it wouldn’t go anywhere, and about three seconds of flame would roll for several yards until it hit a pillbox,” he told me. “When it hit, it was huge, ten or twelve feet in diameter, so it would just penetrate whatever opening was in that pillbox. That’s what I was trying to do when they came charging out. I never knew whether they were out of ammunition or they just decided that the way to get me was to have several of them come with bayonets. I still had flame left, I still had fuel left, so when they came around the pillbox charging at me, I just hit them with a big old ball of flame. That burns bodies up and catches the clothes on fire, and it takes all of the oxygen out of the air immediately and they die.” The smell of burning flesh would haunt Woody for decades.

It was a four-hour fight, and Woody Williams witnessed the event that would become an icon: The American flags being raised on Mt. Suribachi. He was 1,000 yards away from the volcano. “When the flag went up on Iwo, we were still at the edge of the airfield, trying to get across. That was prior to the time that we had gotten across.” The island, Woody remembered, was a nightmare of 800 pillboxes, constructed very closely together with interlocking fields of fire. His war would last another five weeks, and on March 6 he was struck in the leg by shrapnel. “When a corpsman came to me and took care of me, he thought it was bad enough that I should be evacuated. They put a tag on you so that the people coming to help you get back to the rear to the aid station will know who you are and that you’re supposed to be taken back. He put one of those tags on me and told me that I had to go back. I said: I’m not going to go. He wasn’t very happy about that and said very forcefully: Your tag. You must go. We’ve been told before getting into combat that whatever the corpsman says is law. He said: If you’ve got a tag on you, you’ve gotta go. I tore the tag off and said: I don’t have a tag on me.”

All these years later, Woody still chuckles gleefully at the memory: “Then he had to go somewhere else so he didn’t have a chance to put a second one on me. It wasn’t bad enough that I couldn’t continue to fight, and we were down to so few Marines that we needed everybody we could get. The day before that we were down to seventeen in our company. We needed people.”

Woody found out in October of 1945 that he would be receiving the Medal of Honor. Despite all he’d been through on Guam and Iwo Jima, it was getting called to the general’s tent by his first sergeant (he was a corporal) that he found terrifying: “To a little ole country boy who was very shy and bashful and backward it was very nerve-wracking.” When he arrived at the tent, a colonel informed him that he’d need to go inside and stand at attention until the general told him what to do. “I was absolutely frightened. He told me to stand at ease, and then told me some words—I don’t remember what they were.” Those words included congratulations and the announcement that he was headed to Washington via Hawaii. There, he would receive the Medal from President Harry Truman himself along with thirteen others. “I never dreamed I would ever see a president, let alone get that close to one,” and by the time Truman got to Woody, he was a nervous wreck. “My body was shaking and I could not control it. When I walked up to him, he shook hands with me, and then somebody handed him the medal to put around my neck. He did that, and then he laid his left hand on my right shoulder and said to me: I would rather have this medal than be president. He shook hands with me again and kept his hand on my shoulder, and jokingly said he did that so I wouldn’t jump out of my shoes.”

But when I asked Woody which memories truly stand out, it was none of those. “One of the most memorable experiences I’ve carried with me all these years was getting on that airplane [from Guam to Hawaii] with Americans who had been prisoners of war of the Japanese, some of them up to five years. Men that had at one time weighted 170 or 180 pounds now weighed 80 or 90 pounds. They looked like skeletons. They really did. Their cheeks were hollow, their eyes were sunken, you could see every bone in their body. That left a lasting impression on me that I’ll never forget. They were absolutely the happiest people that I think I’ve ever seen in my life because now they were free.” A former POW was sitting next to him, and began to share some of his experience with Woody: the work schedule, the torture. In fact, Woody discovered that his seat on the airplane had been designated for another former POW who had died before he could make the flight. “And then he made a statement I’ve never forgotten: ‘You will never know what freedom is until you have lost it.’ I’ve never forgotten that.”

Woody Williams would struggle with post-combat stress until 1962, torturing himself over the men that he had killed. His father, he recalled, wouldn’t even let them hurt a bird—and he had immolated men with a flamethrower. It was through conversations with a pastor that he came to the Christian faith and, eventually, healing. Like so many other heroes, Williams carried the War with him for the rest of his life. He carries it still.

***

For my grandparents in the Netherlands, the War ended when Canadian tanks rumbled into their villages and drove the Germans out. For most others, it ended when the Americans dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima on August 6, and then on Nagasaki on August 9, 1945. (A few years before he died, I saw Ted “Dutch” Van Kirk, the last surviving crew member of the Enola Gay, which had dropped the bomb on Hiroshima.) I called up veteran journalist Ted Byfield, now in his nineties, to ask him what he remembered of V-J Day, which arrived on August 15, 1945, shortly after the Japanese signed the surrender papers. Ted was working in Atlantic City, and the place exploded in celebration. “I was working in the hotel,” Ted recalled. “People were dancing in the streets and lot of people were drunk and a lot of people were singing. The hotel tried to keep order. Girls would kiss anyone in uniform on that occasion.” A newspaper announcing Germany’s surrender hangs on the wall in my foyer, and a large photo on the front page shows a young woman kneeling in prayer with her son and the bold caption: “THANK GOD!”

What did it all mean? As the world began to discover the details of the Holocaust—which I will examine in the next essay in this series—the sheer extent of Nazi depravity began to become clear. Nobody was fooled, this time around, into believing that this was the Second War to End All Wars. Stalin’s Soviet Union had been the victors, too, and an Iron Curtain spread across Europe, trapping millions in its shadow. For many Europeans, victory pushed them out of the Nazi frying pan and into the Communist fire. The Gestapo was swapped for the KGB and the Stasi, the concentration camps for the gulags. That, too, was yet to come.

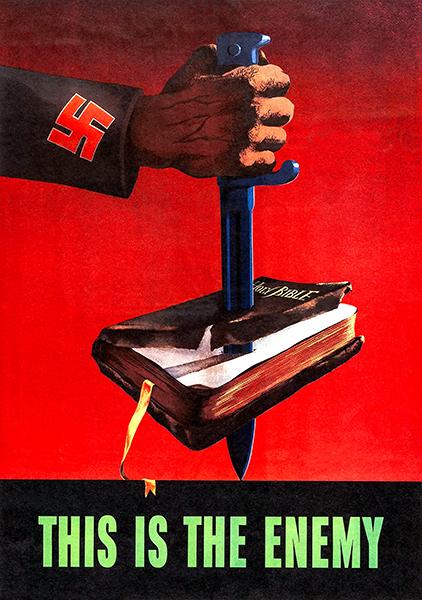

It is interesting to note, firstly, that the Second World War was perhaps the last major conflict waged in the West that was understood by most in Christian terms. Days of prayer to God were held for the Dunkirk evacuation, for the success of D-Day, and other key events. In fact, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt laid this out explicitly in his radio-broadcast prayer for the boys that would soon be surging up the Normandy beaches: “Almighty God: Our sons, pride of our Nation, this day have set upon a mighty endeavor, a struggle to preserve our Republic, our religion, and our civilization, and to set free a suffering humanity.” Our religion. And what was that religion? At the time, the West still understood itself to be a Christian civilization, and the contrast between Christendom and a rapacious regime that was summoning the paganism of the darkest past and fusing it with the wicked social Darwinism of Nietzsche’s nightmares was stark to all. Propaganda posters highlighted the darkness of those who marched under the banner of the twisted cross, warning them that the Nazis sought to crush all that was good, true, and beautiful: The Bible, the family, and faith itself.

Today’s secularists have a hard time remembering how taken for granted this was. Dwight D. Eisenhower, who served as the Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force in Europe, noted in 1952 as president-elect of the United States that “the great struggle of our times is one of the spirit” and that “if we are to be strong, we must first be strong in our spiritual convictions.” Americans, he said, “have got to go back to the very fundamentals of all things. And one of them is that we are a religious people. Even those among us who are, in my opinion, so silly as to doubt the existence of an Almighty, are still members of a religious civilization, because the Founding Fathers said it was a religious concept they were trying to translate into the political world…our form of government has no sense unless it is founded in a deeply-felt religious faith, and I don’t care what it is.”

Today’s secularists have a hard time remembering how taken for granted this was. Dwight D. Eisenhower, who served as the Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force in Europe, noted in 1952 as president-elect of the United States that “the great struggle of our times is one of the spirit” and that “if we are to be strong, we must first be strong in our spiritual convictions.” Americans, he said, “have got to go back to the very fundamentals of all things. And one of them is that we are a religious people. Even those among us who are, in my opinion, so silly as to doubt the existence of an Almighty, are still members of a religious civilization, because the Founding Fathers said it was a religious concept they were trying to translate into the political world…our form of government has no sense unless it is founded in a deeply-felt religious faith, and I don’t care what it is.”

It is thus interesting to note that as the West abandoned the faith and convictions that had been such an essential framework for understanding the world during the Second World War, the War has grown ever larger in our consciousness. In a fascinating (albeit depressing) 2018 book The Phoney Victory: The World War II Illusion, British commentator Peter Hitchens notes that the War had, for Great Britain at least, replaced Christianity as the animating faith and the context through which people understood the world. It was the religion he grew up with: “This war is the dominant theme of serious conversation, a source of metaphors and a frame of thought. It is also our moral guide, the origin of modern scripture about good and evil, courage and self-sacrifice…It is at Dunkirk and D-Day, or in the forests of Burma, or in the prisoner-of-war camps of Silesia or the Far East, where brave Britons of all classes defy their captors or in the freezing midnight clashes between escort ship and U-boat, that we find our lessons about how to be good and live well. The stories of the Good Samaritan and the Prodigal Son cannot compare with this. Even the Crucifixion grows pale and faint in the lurid light of air raids and great columns of burning oil at Dunkirk, a pillar of fire by night, a pillar of cloud by day.”

As the Seas of Faith receded, Hitchens writes, the Second World War took its place as a sort of public religion:

Its passion and parables, and its characters, are nowadays better known than those of the Bible. Instead of the triumphal ride into Jerusalem, the Last Supper and the betrayal at Gethsemane, the Crucifixion and Resurrection, the Supper at Emmaus and the coming of the Holy Ghost in tongues of fire, we have a modern substitute: Winston the outcast prophet in the wilderness, living on cigars and champagne rather than locusts and wild honey, but slighted, exiled, and prophetic all the same. We have the betrayal at Munich, the miraculous survival of virtue amid defeat at Dunkirk and in the Battle of Britain, and the resurrection of freedom and democracy on D-Day. All these are observed with smiling benevolence by the United States of America, godlike in its goodness, wealth and power—especially after its use of man-made thunderbolts at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. This faith’s symbol, in Britain, is the Spitfire, interesting a defensive weapon mainly renowned for saving us from putative invasion.

Hitchens then goes on to debunk this myth, highlighting the horrors of Arthur Harris’s Bomber Command, the fact that the War left Britain broke and America ascendant, and the little-known forced expulsion of German peoples from Poland, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia, agreed to by the conquering powers at Potsdam on August 1, 1945. Hitchens notes that merely pointing out the messy complexities of the War is often met with fury and indignation—much as a religious person would respond to a blasphemy. (And on the subject of unknown stories, a couple of years ago I got my hands on a much-suppressed but truly fascinating book An Eye for an Eye: The Story of Jews Who Sought Revenge for the Holocaust by journalist John Sack, which describes another epilogue to the Second World War that has vanished into history.)

It is interesting to consider Hitchens’ framing of the Second World War as a new public religion when we consider the fact that the term Nazi has become so ubiquitous in our political discourse that it has almost lost its power. Anyone engaged in the public arena—especially with a conservative point of view—will almost inevitably be tarred with this phrase at some point or another (I and some of my fellow students, for example, were referred to as “the Hitler Youth” in a newspaper back in university simply for setting up a pro-life display on campus.) But perhaps the reason that “Nazi” seems to be the fallback slur for those desperate to discredit their opponents is because we can no longer use the words “sin” or “wicked.” If World War II became, in some ways, our framework for good and evil, then even once we did not know who we were anymore, or what evil really was, even when we were no longer, as Eisenhower put it, a religious people, we did know that Nazis embodied all evil. Thus, to be bad is to be a Nazi. Nazi is code for wicked in a culture that no longer understands what wickedness is (and frequently calls wicked things good.)

***

Despite all of that, the very people who enjoy calling their opponents Nazis seem to have forgotten much of what the elites of the Third Reich actually believed. In My Father’s Keeper: Children of Nazi Leaders—An Intimate History of Damage and Denial, Stephan Lebert recounts a conversation with one old Nazi who scorned the condemnation of his beliefs. Today, he pointed out to the author, abortion was now a common tool of eugenics. How was that any better than what he and his Nazi colleagues had undertaken —and with considerable more honesty about the intent?

Robert Wendelin Keyserlingk also recounted several conversations with high-ranking Nazis that reveal why they hated Christianity so much. Alfred Rosenberg, Keyserlingk recalled in his memoir, once told him that “The Communists were right when they would not tolerate the Church. Only if the Church will accept the primacy of the State can it function in a totalitarian system because a man cannot serve two masters—his God and his leader. We cannot tolerate the concept of a Christian conscience which will question the morality of State Acts.” Intolerance of conscience, it goes without saying, has been growing in the West of late.

Joseph Goebbels concurred with Rosenberg, telling Kyeserlingk that the Nazis had to “break the supremacy of Christian conscience by eliminating the hold the freedoms, through religion, have given the Christian Church. It preaches individual salvation. We believe in it only collectively and materially—as a nation.” Collectivists believe in the morality of the herd. Those ideas are becoming, once again, uncomfortably common.

Thus it is that 75 years after the end of the Second World War, Nazis still loom large in our collective consciousness, as their sins have become, for a godless and a post-Christian culture, a replacement for the serpent in the Garden and the evil that dwells in all of our hearts.

What a brilliant essay! Heartbreakingly brilliant. I will be going to the links to read the previous ones. Well done, Sir.

Thank you!