Blog Post

We the Screamers: Why Pro-Lifers Seem Obsessed with Abortion

By Jonathon Van Maren

One of the most common questions I get when conducting training seminars for pro-life activists is perhaps not what you’d expect. It isn’t about the best arguments for the pro-life position; or how to deal with angry protestors; or how to respond to a specific point. It isn’t even about abortion. Usually, it is simpler than that: How do we make people care?

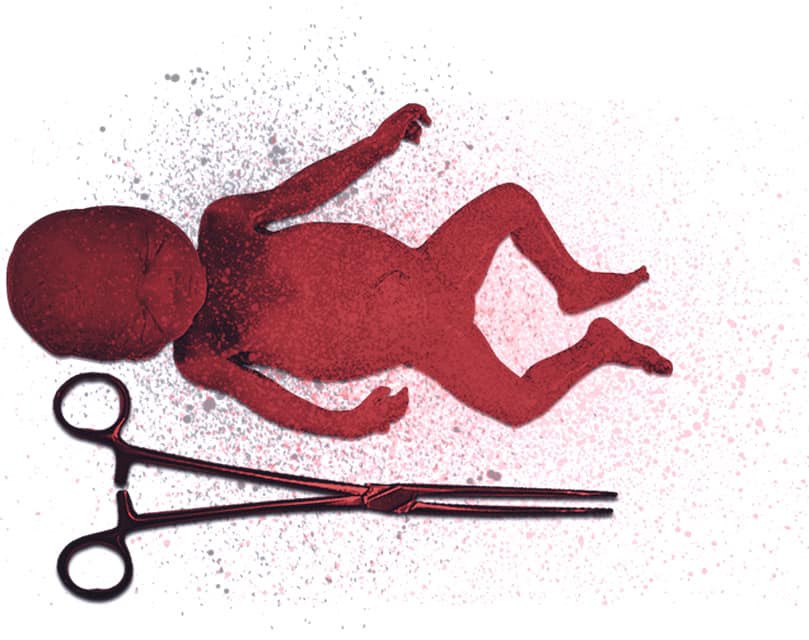

Most people who join the pro-life movement go through a period where all they think about is abortion. For many of us, discovering what abortion really is—the cruel and violent physical destruction of a tiny, beautiful baby in the womb—is a before-and-after sort of moment. Once you see it, you cannot unsee it. Once you know what is happening, you cannot unknow it. Many newly activated pro-lifers simply cannot stop talking about abortion to their friends and loved ones, and this often makes us look obsessive as much as passionate.

It is often hard to communicate this new view of the world to others, and I’ve had more than a few phone calls over the years from parents concerned that their son or daughter is perhaps overdoing it. Caring about abortion is well and good—but people often find the initial intensity to be a bit off-putting. This is exacerbated by the fact that when people first discover what abortion is, they often cannot understand why most folks don’t seem to care—especially pro-life people. If babies are dying horribly every day, why don’t the churches act like it?

Will Rogers once joked that an ignorant person is someone who doesn’t know what you just found out, and I cringe sometimes to remember how I raced around demanding that everyone care more about abortion when I’d scarcely found out about it myself. But the videos I’d watched—of babies having their limbs pulled off and their skulls crushed—really did rock me to my core. Once you realize that your society perpetrates this crime against the youngest and most vulnerable members of the human family, reality just sort of reorganizes itself around this fact, and nothing is ever quite the same again.

Most Christians would readily call themselves pro-life, and would say, without hesitation, that abortion is wrong. Increasingly, I’ve come to believe that the reason so few are passionate about the issue is that abortion is seen as an issue of morality rather than one of justice. Some issues—divorce, contraception, adultery—are issues of morality rather than justice. Some issues, like killing babies, are issues of both morality and justice. Abortion isn’t just “another” issue on a long list of moral positions Christians take by virtue of being Christian. It is coldblooded brutality against children. However, if most people put it in the same category as porn use or fornication, their instinctual response will run to disapproval rather than rescue.

The reality is that most churches don’t understand what abortion is—not really. If each day, hundreds of toddlers, or preschoolers were being shot in major cities across North America, would anybody ask why we were so passionate about it? If toddlers were being decapitated and dismembered, would anyone wonder if we were being too “in your face” about the issue? I think not. But because these babies are invisible and unborn, many people have absorbed the cultural view that they are “other”—that they are somehow not quite as valuable as toddlers, and not quite as worthy of our defence. Nobody would say that, of course. But this reality is implicit to how people often respond to pro-life activism and pro-life activists.

If you find yourself instinctively thinking well, that’s different—therein lies the problem. There are differences, of course. Every injustice has its own unique horrors. But in both of those scenarios, children—created in God’s image to live forever—are being murdered. If those of us who are pro-life forget this, how can we expect the culture to understand it? What if the culture is taking its cues for how seriously to take abortion from the churches? If the culture took abortion as seriously as the churches, would it make a difference?

I am sometimes reminded of an essay by Arthur Koestler, the volcanic anti-totalitarian writer who shot to international fame with the publication of the 1940 novel Darkness at Noon. On January 9, 1944, he published an essay titled “We the Screamers,” which detailed in chilling terms his feeling of inhabiting a different reality than so many of his counterparts. He and a handful of others were sounding the alarm about the ongoing Holocaust, but few seemed to listen:

Here is a dream which keeps coming back to me at almost regular intervals; it is dark, and I am being murdered in some kind of thicket or brushwood; there is a busy road at no more than ten yards distance; I scream for help but nobody hears me, the crowd walks past laughing and chatting.

I know that a great many people share, with individual variations, the same type of dream…I further believe that it is the root of the ineffectiveness of our atrocity propaganda.

For, after all, you are the crowd who walk past laughing on the road; and there are a few of us, escaped victims or eyewitnesses of the things which happen in the thicket and who, haunted by our memories, go on screaming on the wireless, yelling at you in newspapers and in public meetings, theatres and cinemas. Now and then we succeed in reaching your ear for a minute. I know it each time it happens by a certain…wonder on your faces, a faint glassy stare entering your eye; and I tell myself: Now you have got them, now hold them, bold them, so that they will remain awake; but it only lasts a minute. You shake yourself like puppies who have got their fur wet; then the transparent screen descends again and you walk on, protected by the dream-barrier which stifles all sound.

This reminds me of how I felt when I held a dead, murdered little baby in my hands. How do you convey to people that abortion isn’t a cause so much as an emergency? How do you explain that this destruction is happening here, now, all around us? That silent screams stifled by mothers’ bodies end in crimson tide of death in clinics in every major city while millions go about their lives around the deathly quiet carnage? It all sounds so melodramatic, so unreal—unless it is true.

As Koestler writes, it is often difficult to reconcile these two realities that coexist, but should not coexist:

Clearly all this is becoming a mania with me and my like. Clearly we must suffer from some morbid obsession, whereas the others are healthy and normal. But the characteristic symptom of maniacs is that they lose contact with reality and live in a fantasy world. So, perhaps, it is the other way round: perhaps it is we, the screamers, who react in a sound and healthy way to the reality which surrounds us, whereas you are the neurotics who totter about in a screened fantasy world because you lack the faculty to face the facts…

There have been screamers at all times—prophets, preachers, teachers and cranks—cursing the obtuseness of their contemporaries, and the situation-pattern remained very much the same. There are always the screamers screaming from the thicket and the people who pass by on the road. They have ears but hear not, they have eyes but see not. So the roots of this must lie deeper than mere obtuseness…I know one who used to tour this country addressing meetings, at an average of ten a week. He is a well-known London publisher. Before each meeting he used to lock himself up in a room, close his eyes, and imagine in detail, for twenty minutes, that he was one of the people in Poland who were being killed. One day he tried to feel what it was like to be suffocated by chloride gas in a death-train; the other he had to dig his grave with two hundred others and then face a machine gun, which, of course, is rather unprecise and capricious in its aiming. Then he walked out to the platform and talked. He kept going for a full year before he collapsed with a nervous breakdown. He had a great command of his audience and perhaps he has done some good; perhaps he brought the two planes, divided by miles of distance, an inch closer to each other.

I think one should imitate this example. Two minutes of this kind of exercise per day, with closed eyes, after reading the morning paper, are at present more necessary to us than physical jerks and breathing the Yogi way…For as long as there are people on the road and victims in the thicket, divided by dream barriers, this will remain a phoney civilisation.

It is a testament to the moral schizophrenia that lives in all of us that Koestler was so clear-eyed about totalitarianism and the injustice that accompanies it while being blind to the cruelty of abortion that I am writing about here. He was, by all accounts, brutish towards women in his personal life, and forced several lovers into illegal abortions while refusing to meet the one child that did survive. There are many like him—people who recognize injustice in many places but refuse to see it in their own backyards or their own lives. After all, it is easier to rage against the wickedness of other places than to recognize the deadly flaws in our own.

I write this not to point fingers at anyone or to make any accusations, but merely to attempt an answer to those who wonder why pro-life activists can seem so obsessive. It must be mentioned that the pro-life movement exists because thousands of people sacrifice their funds to keep the work going; their time to reach people; their talent to develop new ways to reach people. We wouldn’t be able to do this work if it weren’t for a huge number of people who support the pro-life organization(s) we work for. Still, these partners in the fight are a small minority in this culture.

We all inhabit the same reality, but I think we often see it very differently—or at least, from different angles. After all, the beauty and the blessings are just as real as the ugliness and the death. And this is not to say that pro-life activists can face the truth about abortion every day. To do that is to court breakdown. Nobody can carry the burden of so many innocent dead constantly; we would not be able to function if we did. Plenty of activists have tried and burned out as a result. It is to say that these dead innocents lurk at the peripheries of our consciousness, reminding us that the world we see around us is built on blood.

I am fully aware that this sounds dark, morbid, and a little dramatic. I know some will read these words and brush them off as obsessive. But only one question needs to be answered: Is it true? If you are pro-life, as I am, you must admit that it is. And if you admit that, and you listen closely, perhaps the fever-dream of our phoney culture will be broken and you will hear—as we do—the screams coming from the thicket.

Si può avere traduzione in italiano? È molto interessante e prezioso capire e diffondere.Grazie